Inspirations Taken From the Brontë Masterpieces

By Summer Strevens

It is a commonly held romantic assertion that the predominant geology of ‘Brontë Country’ – that of Millstone Grit, a dark sandstone which lends the crags and scenery thereabouts an air of bleakness and desolation -– fueled the imaginations of the Brontë sisters in writing their classic novels. While Charlotte, Emily and Anne are doubtless influenced by the landscape surrounding the family home in Haworth, now the Brontë Parsonage Museum and a place of pilgrimage for Brontë enthusiasts the world over, the timeless windswept prospects of heather and wild moors thereabouts bordering onto Lancashire are not the sole inspiration for their enduring works of romanticism, embodying a cold hard reality with profound insights into humanity; the scenery, and indeed the folklore of the Yorkshire Dales are also embodied in their narratives, so widely read, retold and enjoyed to this day.

To begin with, the primary setting as well as one of the characters in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, her Gothic masterpiece which became the sensation of Victorian England, are drawn from her visit to a manor house in North Yorkshire, Norton Conyers House, near Ripon. In 1839, while Charlotte is staying at Norton Conyers she is fascinated by her host’s stories of a mad woman who has been confined in the attic of the hall sometime in the 18th century.

“The reality of a miserable marriage”

Possibly epileptic, or pregnant with an illegitimate child, when Brontë later comes to write Jane Eyre, published some eight years later, she remembers this story, and the ‘madwoman’ of Norton Conyers becomes the model for the psychotic Bertha Antoinetta Mason, the violently insane first wife of Edward Rochester. Having been duped into marriage with this wealthy, famed beauty of Creole heritage (Rochester explains in the novel that he was unaware of the violent insanity that ran in his bride’s family, the past three generations having succumbed, it is clear that the Mason family want Bertha off their hands), when Rochester returns to England with his new wife he has her imprisoned in one of the attic rooms of Thornfield Hall under the care of Grace Poole, a hire nurse who keeps her frenzied charge in check while Rochester travels abroad to escape the reality of his miserable marriage.

Many details of Norton Conyers are incorporated in the descriptions of Rochester’s ancestral home, Thornfield Hall, the real and fictional halls, in Brontë’s words, “three storeys high, of proportions not vast, though considerable, a gentleman’s manor house, not a nobleman’s seat”. Both have battlements, a rookery, a sunken fence and wide main oak staircase, and in 2004 the discovery of a secret blocked staircase at Norton Conyers, linking the first floor to the attics mirrors the staircase vividly described by Brontë in the novel, the real life hidden flight of stairs that were the inspiration for those leading from Mr Rochester’s grand bedroom to his mad wife’s miserable attic prison.

“Sales are initially poor”

The recent discovery is made on the landing outside the Peacock Room. This room is the supposed model for Mr Rochester’s quarters. Behind a section of wood panelling which rings hollow when knocked, a musty flight of steps, just wide enough for one person, leads from the attic. A chink of light reveals a disused door with an ingenious spring lock. Though the existence of the secret staircase is hidden by the thickness of the panel wall since the 1880s, when the landing was remodeled, the door at the bottom would have been visible originally. And certainly at the time of Charlotte Brontë’s visit.

The maniacal Bertha Mason as illustrated by F H Townsend for the second edition of Jane Eyre published in 1847.

image: Wikimedia Commons

Thankfully Norton Conyers has never been subject to the fiery fictitious destruction that befell Thornfield Hall. This tangible connection to Charlotte Brontë’s inspiration is publicly available on special open days throughout the summer months.

Turning to Emily, the middle of the literary trio of Brontë sisters (Charlotte was the oldest born on 21 April 1816, followed by Emily born on 30th July 1818 and Anne who was born 17th January 1820). Like her sisters, she writes under a masculine pen name, Ellis Bell. Her male identity allows her work a broader audience in an era when authoresses deal with severe prejudice. Nevertheless, although the author conceals her real gender, when her towering romantic fiction Wuthering Heights comes out in 1847, the sales of what was to become such an enduring classic are initially poor. As Emily dies the following year, aged 30, sadly she is never aware of her subsequent success.

“Harsh treatment”

As for the part the Dales play in Emily’s inspiration for the novel, we must look to her childhood. Especially her time spent at the Cowan Bridge Clergy Daughters’ School. Which is, incidentally, another of Charlotte’s inspirations – the model for the foreboding Lowood Institution in Jane Eyre.

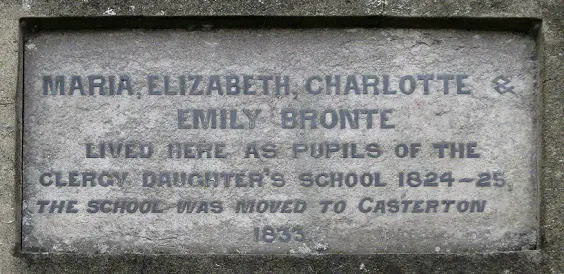

The school is on the main route from Leeds to Kendal. It is little over two-miles from the historic market town of Kirkby Lonsdale. Between 1824 and 1825 Emily, Charlotte and their elder sisters Maria and Elizabeth attend the school. Here, regimes are rigorous and the conditions for borders austere. Maria and Elizabeth both contract tuberculosis while there. In part this is due to the school’s harsh treatment and unsanitary practices. The Reverend Brontë hastily removes his daughters from the establishment. Maria and Elizabeth both die at home shortly afterwards aged 12 and 10 years respectively.

Dedication plaque on the side of the former school – the model for Charlotte Brontë’s foreboding ‘Lowood Institution’ in Jane Eyre.

The Cowan Bridge Clergy Daughters’ School as it appears today, now a private residence.

(Photographed with the kind permission of the owners Martin and Sam Jebb)

Emily’s time at Cowan Bridge is brief. She nevertheless gains exposure to the local gossip. She listens to inhabitants of Dentdale, who are amongst the domestic staff at the school. They also attend the Sunday services at the same church that the girls are forced to walk three miles to every Sabbath, in the village of Tunstall, regardless of the weather.

“One of the greatest romantic characters”

Later in life, drawing on the recollections of overheard conversations, it seems that Emily’s creation of the character of Heathcliff is based on these childhood memories. The parallels between supposed fact and fiction are too close. The source must have been her real life inspiration. Controversially the nature of the old rumours that circulate around Dentdale also raise a further question. Does Emily’s description of Heathcliff’s skin as “as dark as though it came from the Devil” support another conjecture? That one of the greatest romantic characters in 19th century English literature was, in fact, black.

Returning to the supposition that the dark-skinned Heathcliff is inspired by real events that took place in one of the most isolated parts of northern England, this gains support by the history of the wealthy Sill family. They are the one time residents of Dentdale. Also owners of High Rigg End, on the flanks of Whernside. The family’s fortune comes not from farming, but from the inherited ownership of ‘Providence’. This is a sugar plantation in Jamaica worked by about 200 slaves. It is bequeathed by one John Sill, described as a ‘Gentleman from Jamaica’.

Memorial in St Andrew’s Church, Dent, to the memory of “John Sill Esq of Providence in the island of Jamaica”

That the Sills bring slaves to Dentdale to work as their servants is proven. A Liverpool newspaper advertisement is discovered. It is placed in 1758 by Edmund Sill of Dent. A “handsome reward” is offered for the return of a slave who has escaped. He is said to be named Thomas Anson, “a Negro Man, about five feet six inches high, aged 20 years or upwards”.

“Local scandal”

It would appear that Emily wove various strands of the Sill family history into Wuthering Heights. Striking comparisons are drawn between fact and fiction. The Sill family’s adoption of a white orphan boy called Richard Sutton, described as a ‘foundling’ and brought to Dentdale by Edmund Sill in the late 1780s, seems to echo Emily’s depiction of Heathcliff’s early life. The boy is treated no better than a servant. They keep him with the family slaves rather than bring him up with the Sills’ three sons and only daughter.

After the deaths of Edmund and Elizabeth Sill and their three sons, (all are deceased by 1807) their surviving unmarried daughter Ann inherits the estates. Sutton rises to become the estate manager, supposedly developing a ‘relationship’ with Ann. Sutton now lives in the bleak High Rigg End, while Ann lives the life of a lady at West House. Just as Heathcliff lives in the remote moorland farmhouse of Wuthering Heights and Catherine Earnshaw resides at Thrushcross Grange. However, Emily seems to blend another related local scandal into the doomed lovers’ fates. She draws on the tale that Ann had supposedly fallen in love with a black coachman.

“Immerse in the beauty”

It is whispered that the coachman subsequently disappears without trace. Ann’s brothers deem that such a relationship falls outside the bounds of propriety. A human skeleton is found beneath the floor of the family home a century later in 1902. It is assumed to be the remains of Ann’s lover.

Though the possibility of a black Heathcliff somehow never registers with those film producers responsible for the numerous screen adaptations of the story, for the first time a black actor is cast as Heathcliff in the 2011 version of Wuthering Heights. This reinforces the hypothesis that a local slave is, in part, Emily’s inspiration. As for Dentdale itself being the wild and boundary-less backdrop to unfolding drama of Wuthering Heights? Well, various other localities are mooted as stronger candidates. But it is still possible to immerse oneself in the natural beauty of the desolate yet stunning heights and valleys of this ‘Hidden Dale’, “whence a light mist mounted and formed a fleecy cloud on the skirts of the blue.”

Top image: Dentdale looking north from Rigg End Farm. A candidate for Wuthering Heights, the home of Emily Brontë’s literary heroine Catherine Earnshaw

This article was drawn from ‘Before They Were Fiction’ by Summer Strevens, available now from Amazon.

This article was drawn from ‘Before They Were Fiction’ by Summer Strevens, available now from Amazon.