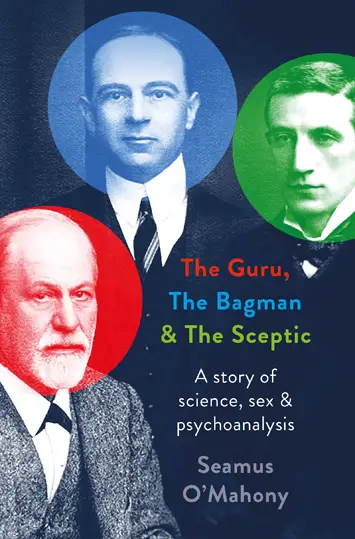

The Guru, the Bagman and the Sceptic by Seamus O’Mahoney – Review

By Barney Bardsley

This account of the birth of psychoanalysis in the early 20th century is a rip-roaring page turner of a book from start to finish. If you go to it expecting a scholarly and cerebral dissection of Freud and his controversial practise and theories, then you will be disappointed. But if you want to be royally entertained by the outrageous – not to say occasionally dodgy – goings-on in Vienna, Cambridge and London, under cover of the new ‘scientific’ technique, then this is certainly the book for you.

Seamus O’Mahoney has chosen three main characters for his biography: Freud himself; Ernest Jones – Freud’s closest ally and disciple; and Wilfred Trotter, a gifted surgeon and brother-in-law to Jones. It is an unusual approach, to include a medical doctor here, who was, after initial interest, deeply sceptical of psychoanalysis. But Trotter proves to be a refreshingly straightforward witness to the times, and is as sober and reliable in his behaviour as the other two are maverick and quixotic. A still voice of reason, in the middle of a stormy new psychoanalytic age.

It is not surprising to learn that the author is himself a medical man and former hospital doctor – and he is undoubtedly skewed in his attitude towards the three men he writes about, reserving all his praise and admiration for fellow doctor Wilfred Trotter, with plenty of arch commentary on Freud and Jones. Trotter was a contemporary and friend of Ernest Jones, who rose to become an eminent surgeon (even treating Freud himself in the final stages of Freud’s cancer). An interesting character, he comes across as consistently high minded, trustworthy, and eminently sane. The other two? Not so much…

As O’Mahoney writes in his introduction, Freud, both as a man and as an eminence grise, seems to have become “unassailable” in status. And his place in history is assured, as the originator of a remarkable and powerful theory of mind, and a working practise – the fifty minute psychoanalytic hour – used to this day as a talking cure, for those with troubled minds and very deep pockets. But O’Mahoney also admits that, “Although I admire Freud, psychoanalysis has always bothered me; I have written this book partly to find out why.”

“Fascinating and terrifying”

“Fascinating and terrifying”

Anyone who reads his book will surely be bothered, too. Freud’s deeply partisan approach – using theories that could not be proved, and practises that were at times ethically questionable – would, in our contemporary era, be subject to close, and possibly horrified, scrutiny. The early psychoanalysts thought nothing of sleeping with their patients. They had plenty to say about the apparent ‘hysteria’ of women. They analysed each other’s children; they even analysed their own children. This analysis went on for years, but never, muses O’Mahoney, seemed to make anyone better. It was, moreover, a singularly elite club of people who could afford the time and the money to give themselves over to such a complex and lengthy process. Freud was an undisputed Titan of his age, and he longed for his techniques to be accepted as a bona fide science. But they never were. Still, his theories remain compelling fodder for thinkers of every persuasion, both in the sciences and the arts. He was, as described in this book, fascinating and terrifying, in equal measure. A troubling, murky genius.

Ernest Jones – who became one of Freud’s most steadfast acolytes, and rose to a position of great power and influence in psychoanalytic circles – shared none of the integrity of Trotter, or the originality of Freud. He comes across as a rather seedy individual, who used an ebullient charm and self belief to conceal his sexual excesses: hiding in plain sight, in various professional guises, whilst he did what he liked with any female unable to stand up to his advances. Already in 1906, he was charged with gross indecency, carried out on girls with learning difficulties, during his medical inspections of the schools they attended. Undeterred by this, he went off to Vienna to study with Freud, then to Canada (where he was again accused of sexual misconduct), then back to London, where he practised for years as a psychoanalyst, wrote and published papers, and seemed to survive – even thrive on – any scandal that embroiled him along the way.

Nobody, except for the dignified Trotter, comes off particularly well in this account. All the people named are described as self obsessed, even, at times, delusional and abusive. But a whole generation of privileged and clever young people – including leading literary lights such as members of the Bloomsbury set, Samuel Beckett, Isiah Berlin – revelled in the heady mind games of the new technique. Says O’Mahoney, “The dressing up of this prolonged immersion in the self as a ‘scientific’ and ‘therapeutic’ process was intoxicating.” But was it all just smoke and mirrors? An excuse to indulge in physical and emotional excess, sometimes at the expense of individuals too fragile to withstand the process? The author certainly presents a compelling, and rather damning, argument to suggest so. But I fear this book is too heavily biassed against the whole psychoanalytic tradition, which, despite its myriad controversies, remains one of the great human endeavours of the twentieth century. Still, taken as pure entertainment, with characters larger than life – and twice as nasty – romping through its pages, and each new escapade more scandalous than the last, this book remains a confident and hugely enjoyable read.

‘The Guru, the Bagman and the Sceptic: A story of science, sex and psychoanalysis’ by Seamus O’Mahoney is published by Head of Zeus