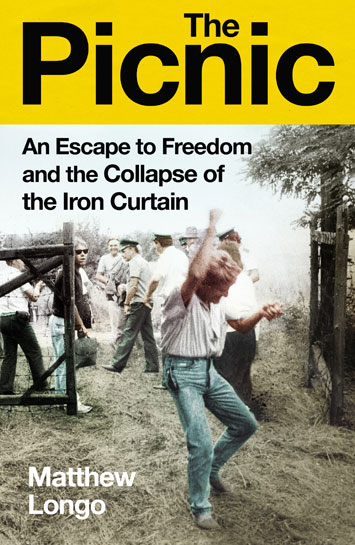

The Picnic by Matthew Longo – Review

By Barney Bardsley

For those old enough to remember it, the fall of the Berlin Wall must count as one of the most seismic – and joyful – world events of their lives. It was a momentous turning point in the global politics of the twentieth century. After being frozen in a Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union for most of the second half of that century, the world now welcomed a new rapprochement between East and West, that positively fizzed with possibility.

But what usually gets overlooked in this story is the role played by one of the Soviet Union’s smallest satellite states – Hungary – in opening up the road to democracy and freedom in the first place. It was Miklós Németh, the reformist head of the Hungarian government, who executed a plan to cut the electric wire fence at Hegyeshalom – a border crossing between Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Austria – on 2 May 1989, a full six months ahead of the fall of the Berlin wall. He had already informed fellow reformer and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev of his intentions, and, when he received no objection, he went right ahead and did it. It was a symbolic act, but also the first domino to fall, in a cascading chain of events that year.

The atmosphere in Hungary was already ripe for change. Since 1956, when they were the first of the Soviet-dominated states to rebel, in the bloody October Uprising, the Hungarians always managed somehow to go their own way. This earned them the affectionate name of “the happiest barrack in the Eastern bloc”. On 16 June 1989, there was a huge demonstration in Budapest, to mark the events of 1956, and to enact a symbolic reburial of Hungary’s martyred leader, Imre Nagy, who was executed by the Soviets following the Uprising. I was living in Hungary at the time, and went to the ceremony. There were thousands upon thousands of people out on the street. It was clear that something big was beginning: a swell of change, that simply could not be stopped.

In Matthew Longo’s book, he documents this time, and, more crucially, the events of 19 August, 1989, when the border between Hungary and Austria was not just symbolically opened, but forcibly breached, with hundreds of people stampeding their way to freedom – and leading directly to the fall of the Berlin wall, and, effectively, the collapse of the Soviet empire.

Longo’s book reads as part history, part thriller, as he weaves together interviews from participants, official documents, and political analysis, to paint a compelling and dramatic picture of events as they happened on the ground. He has certainly done his homework. There are stories here from Hungary and East Germany – accounts of families torn apart, and of daring escapes, as well as rueful recollections from those tasked with controlling the (unarmed) insurgency as it was taking place. It all makes for a riveting read, and a poignant one too. Much was lost in the process of this great liberation – and it is doubtful that anyone could have predicted the massive swing to the repressive right that has happened across the former Eastern bloc in the intervening years. But it had an inevitability to it, even if everything seemed haphazard, confused, chaotic at the time. The people will have their say: and in 1989, the people had had enough.

“Courageous and bold”

The picnic of the title was the Pan European Picnic, organised by activists on 19 August 1989, at Sopron, a border town between western Hungary and Austria. It was first mooted as a chance for gathering and discussion only, but the posters advertising the event rather gave away their true intention. “Bontsd és vidd!” was the slogan. “Tear it (the border fence) down and throw it away!” And that is exactly what happened. Hundreds of Hungarians and East Germans gathered by the lake and woods of the border, and, as the picnic progressed, they grew more restive and resolved, until finally the gates were breached and people swarmed through to the West, never to go back. Hungary had long been a holiday destination for East Germans, as it was the most relaxed destination in the Eastern bloc, and a place where they could legally reunite with those in West Germany whom they were otherwise forbidden to see. The East Germans would camp at Lake Balaton for much of the summer – only in this particular summer, the camping trip turned to the flight of their lives.

The picnic of the title was the Pan European Picnic, organised by activists on 19 August 1989, at Sopron, a border town between western Hungary and Austria. It was first mooted as a chance for gathering and discussion only, but the posters advertising the event rather gave away their true intention. “Bontsd és vidd!” was the slogan. “Tear it (the border fence) down and throw it away!” And that is exactly what happened. Hundreds of Hungarians and East Germans gathered by the lake and woods of the border, and, as the picnic progressed, they grew more restive and resolved, until finally the gates were breached and people swarmed through to the West, never to go back. Hungary had long been a holiday destination for East Germans, as it was the most relaxed destination in the Eastern bloc, and a place where they could legally reunite with those in West Germany whom they were otherwise forbidden to see. The East Germans would camp at Lake Balaton for much of the summer – only in this particular summer, the camping trip turned to the flight of their lives.

There are many small details in this book that have remained hidden for years, and, as such, The Picnic is an important document of witness, as well as a compellingly good read. The most shocking elements of the story concern East Germany, which was the most repressive of the entire Eastern bloc. The Stasi, the secret police, infiltrated every aspect of public and personal life. Neighbour reported on neighbour; husband on wife; child on parent. Nobody felt safe: nor were they. It’s hardly surprising then, that the picnic itself was invaded by swarms of Stasi, which makes the actions of the picnickers all the more courageous and bold.

Perhaps the bravest of all the people mentioned here are actually the least expected candidates. One is Árpád Bella, who was the Hungarian commanding officer on duty at the border on the day of the picnic. As the refugees started to breach the fence, he had a choice to make: start shooting, or let them through. It could have been a bloodbath, but he decided otherwise. He stood aside, and let the people through. It was a great risk to him personally, and there were repercussions afterwards, but he took the moral high ground, and, in doing so, he changed the course of history. His counterpart, East German Harald Jäger, was the officer in charge at the northern crossing point of the Berlin Wall on 9 November. It was he who gave the order to his men, at 11 pm, to “Open up!” and to lay down their arms, as people began tearing at the bricks and stones of the wall.

Longo interviewed both of these men for his book, and neither feels particularly proud of their actions. Jäger (a long time Stasi apparatchik) even confesses that, had he known how things would develop after German reunification, he would not have acted as he did. Nonetheless, both Bella and Jäger played an honourable part in the liberation of many from the totalitarian yoke.

It is hard now, to recollect the euphoria of those days. And Longo is sanguine in his reflections: “The transition to capitalism was abrupt and poorly regulated. People tried to be patient, but in many ways it was a bloodletting. A transition, not from Communism to capitalism, but from one form of servitude to another.” Still, it was a powerful moment in history, and the author has served it well, with an account that is thoughtful, gripping and thoroughly well researched.

‘The Picnic: An Escape to Freedom and the Collapse of the Iron Curtain’ by Matthew Longo is published

by The Bodley Head