Noughts and Crosses – Review – York Theatre Royal

By Elizabeth Stanforth-Sharpe, September 2022

It’s hard to appreciate that Malorie Blackman’s novel for Noughts and Crosses is over 20 years old. It was ground-breaking in confronting readers as young as nine with a multiplicity of issues – racism, conscious and unconscious bias, mental health, repressive education systems, suicide, alcoholism, extremist groups, the challenges of adolescence, sexual discovery, social inequalities, and forbidden love, opening avenues for discussion and provocation. In winning the 2002 Children’s Book Award, the work, ostensibly written for young adults, went on to reach a wider demography, and it has never been far from public consciousness since.

Pilot Theatre is an international, award winning, Touring Theatre Company, based in York and fully focussed on making high quality theatre, schools’ workshops, and educational packs for younger audiences, which engage young adults in confronting the big issues of the world they are immersed in. Pilot commissioned the first theatrical adaptation of Noughts and Crosses in the summer of 2016, following the Brexit referendum, the tragic murder of Jo Cox by a far-right activist, and escalating evidence that racist and xenophobic attacks had increased as a direct result of the vote. Sabrina Mahfouz adapted Blackman’s work, Esther Richardson engaged a wonderful team of Black and global majority artists and Noughts and Crosses began its first tour in 2019. Then Covid-19 hit the world.

“Fight against hate and discrimination”

This was, however, far too important a subject for the sets to be just stored away, the creatives let go of, and the play abandoned. Lockdown brought a huge increase in race hate crimes, and as the world emerged, the evidence was staggering. Racially motivated hate crimes remain the highest reported type of hate crime in the UK. A total of 85,268 racially aggravated offences were recorded in 2020/2021 – up 12% on the 76,158 in 2019/2020, and according to Victim Support, race and nationality hate crimes rose by a shocking 73% in 2021. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter movement, the pursuit for racial justice has turned a corner, where conversations now go beyond how to prevent racist incidents, but also how it manifests from stereotypes, prejudice, and lack of knowledge.

Becoming educated on hate and discrimination at an early stage is the major key to preventing it from happening. Pilot recognised that, in their adaptation of Noughts and Crosses, they had a significant vehicle that could be used across educational, corporate and community sectors in the fight against hate and discrimination in all its forms. Mahfouz was asked to re-visit the script and bring its relevance back up to date, which, with utter heartbreak, we must resoundingly admit that it still has.

“Brushed off”

Noughts and Crosses is essentially the story of Callum and Sephy. A Romeo and Juliet type, if you like. Callum is white and a nought (lower case letter usage is significant and intentional). Sephy is black and a Cross. noughts are second-rate citizens. Crosses are the ruling class. There is a very strict, very clear divide between the two groups, but Callum and Sephy have known each other since they were children, their friendship has given way to teenage romance, and they are determined to fight against the enduring tide that is race and prejudice, justice and oppression, what they feel is rightfully theirs and what society say is rightfully theirs.

Yet the battles they face are not only of politics, but also within themselves. Callum believes he is capable of far more than the opportunities that the Crosses will allow him. He is angered and insulted by the Cross government’s “attempt” at “integration.” He wants equality but struggles to find the right course… and how does he reconcile all of this with the love he feels for someone who is a member of the very people who oppress him?

To love Sephy means to love the source of all his pain, hatred and anger. And yet, Sephy isn’t like them at all. Her people’s inability to see their crime and her desire to fight for Callum’s rights becomes a full-time job. Unceasingly, she persuades correct perspective to Crosses, but is brushed off as ignorant. She continually tries to extend her hand to the noughts, but her sympathy is falsely taken for pity and mockery. Callum himself is tired of being in her debt. There are so many things working against their happiness that there is tension even when they try to help each other.

“Fast paced”

Can there ever be a hopeful resolution, and if so, what will be the ultimate price that is paid?

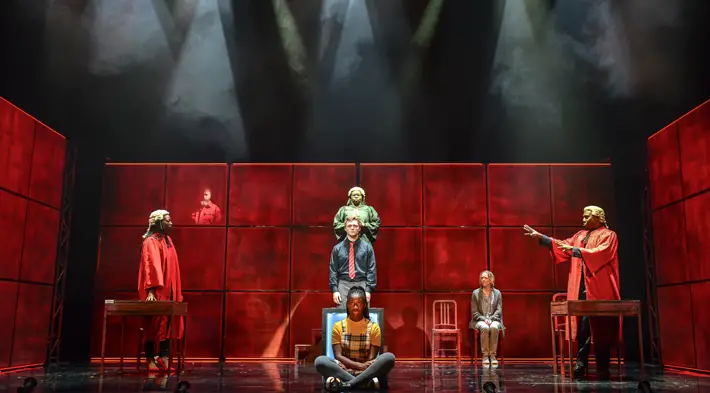

Simon Kenny, as designer, and Ben Cowens, as lighting designer, have created a theatrical atmosphere that is as much a part of the story as the text. Blackman placed her novel in a world that had key points of recognition with ours, and yet was strikingly unfamiliar in others, and Mahfouz’s adaptation is fast paced, with scenes weaving into each other; the full focus for the designers needed to be on a space where the events, emotions and dialogue were the most important elements in an environment that suggested, rather than described.

They found their inspiration in infrared photography of cityscapes, where colours are reproduced faithfully, except for green, which has its interpretation as red, effecting a scenography that is familiar, and yet different. Colour perception varies across cultures, and some languages do not have words for colour per se, but, universally, there are words for black, white and red; the descriptors of survival.

“Complicated role”

Red, the colour psychologically associated with power, aggression, blood, passion, danger, action and provocation is liberally strobed and daubed across the black stage, and appears in telling snatches of costume – for example, the defence lawyer wears scarlet stilettos that betray whose side she is serving, and as the play opens, Sephy and Callum wear similar black and white outfits, as couples in plays often do, but his shirt has touches of red overlaying the pattern as a subtle nod that this relationship is with someone from a ‘forbidden’ world.

James Arden and Effie Ansah are both taking on their first leading roles on stage in this production, as Callum and Effie respectively. These are robust, emotional and energetic roles for any actor to deal with, and they can both be extremely proud of their outstanding execution of hard material. Also making his professional debut is Tom Coleman, taking on the complicated role of Andrew Dorn, the second in command of the Liberation Militia, but also understudying both Callum and Jude; a demanding, more than competent start to his career.

“Unnerving”

Steph Asamoah graduated in 2021 and takes on the role of Minerva, Sephy’s flouncing, truculent, and ultimately, betraying, older sister. Abiola Efunshile admirably shifted between the roles of Lola, the aggressive school pupil who beat Sephy up for sitting at the noughts’ meal table, and Kelani Adams, the lawyer in the pay of Jasmine Hadley, who has a reputation for being effective and ruthless. Amie Buhari, as Jasmine Hadley, has command of a multi-layered character whose struggles give the audience an insight into just how complex some of the issues of the play can be.

Daniel Copeland reprises his role as Ryan, deftly switching from an ineffectual, passive man who has never raised his voice to his children, to someone filled with anger following his daughter’s death, though still showing himself to have family at his heart as he carries the can for Jude’s misdemeanours. The Home Office Minister, Kamal Hadley, opposed to any social equality between the Crosses and the noughts, cruel to his wife and expecting that his family will do nothing to tarnish his public image, is played with suitable aplomb by Chris Jack.

Nathaniel McCloskey is unnerving as Jude, Callum’s resentful, furious, and scary older brother. Emma Keele supplies the balancing sense of reason to the McGregor family as Meggie, the protective wife and mother who believes in non-violent process as a path to racial equality. Together, this is a formidable ensemble, and under Richardson’s astute direction, they give Mahfouz’s writing the gravitas and propulsion it deserves.

“Strength”

Noughts and Crosses is a work that is geared towards young adults, from Blackman’s first novel through Mahfouz’s sensitive adaptation, to Pilot Theatre‘s expert handling. It touches most who watch, but most heartening of all was to see York Theatre Royal filled with young people, clearly moved and engaged with what they were viewing. Their lively discussions during the interval showed clearly that the cast and creatives had done all they had set out to accomplish, and done so with style and strength.

Noughts and Crosses continues its UK tour until Easter 2023, and I can only imagine the power it gathers as it continues its journey, conveying a message that isn’t solely about race, but is about standing up for what you know is the right thing to do, being compassionate, understanding, fair, egalitarian and accepting of all.

images: Robert Day