The Historic Gangs of Sheffield

By Ben W. Johnson

‘In a war, whichever side may call itself the victor, there are no winners, but all are losers.’

Neville Chamberlain, British Politician (1869–1940)

As a major industrial city, Sheffield has always been a place where the mood of the nation is reflected in its residents. Very little takes place in London which does not spread north to the metropolises of Sheffield, Manchester, Leeds and other large cities. Unfortunately, this trend also includes the spread of negative events and behaviours. Therefore, it is little wonder that the growth of gang culture which grew from the slums of London due to the ever-decreasing quality of life experienced by its inhabitants, would eventually travel north; such were the plummeting living conditions and rocketing populations of the vast northern industrial centres.

It has always been the case that disaffected youths find meaning in challenging authority, but in most cases, this is nothing more than a rite of passage before embarking on a well spent life. Yet, it would seem that when times are particularly hard, the transition between angry youth and contented adult is a much wider gulf than would normally be the case. People have always fought for several things, the wellbeing of their families, a sense of worth, and the respect of others amongst other factors. The residents of Sheffield have always been a spirited bunch, but the socially aware and politically savvy activists of the modern city bear little resemblance to those who preceded them.

“Civil disobedience”

The causes may be the same, but the means of protest have, thankfully, evolved into peaceful and reasoned debate in most cases. We may not be perfect in the north, but we’re a damn sight more reasonable than our forefathers it would seem, as the history of the city is awash with tales of gang violence and organised crime. We protest now as it is our right to challenge authority; our civil disobedience is nothing more than a chance to express our opinions. Yet, in times gone by, civil disobedience was undertaken for very different reasons, as the ghosts of the past were victim to a society in which they were largely invisible, and any chance of gain was there for the taking.

The first real gang to make an impact upon the ordinary lives of the northern working class was the Northern Mob, which originated in the 1840s, and was made up of several local groups from as far away as Liverpool, Manchester, Derby and Nottingham. The mob included a large representation from Sheffield, as one would expect from such a growing industrial city. As is the case in so many gang tales, the main driving force behind the Northern Mob was financial gain.

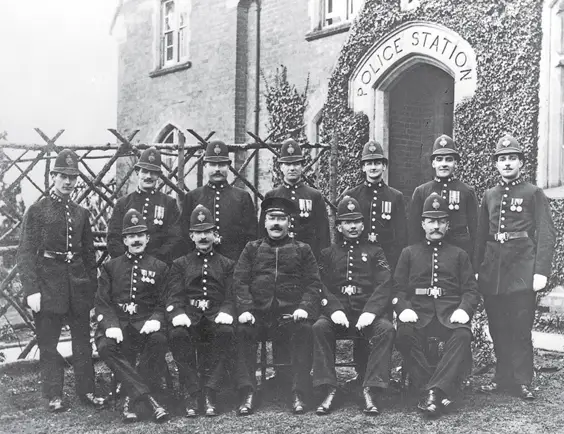

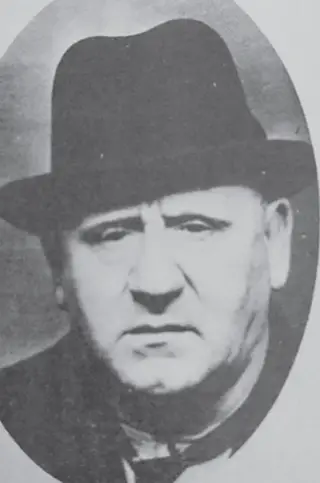

Samuel Garvin, leader of The Park Brigade, and feared gangster

image courtesy of ‘The Sheffield Gang Wars’ by J.P. Bean

“Offering protection”

The mob would mobilise at almost any event that could guarantee a high turnout of wealthy visitors. Agricultural shows, race meetings, boxing matches and animal baiting events were always targeted, as the chance to extort money by means of deception or sheer intimidation were always rife on these occasions. There were very few times when a wealthy Londoner would not part with his money when being surrounded by a large and unruly gang of northern thugs.

However, as time passed and the cities grew even further, the co-operative approach of the Northern Mob seems to have fallen by the wayside. There were now wealthy aspects of every city, and it no longer became necessary to join forces against the Champagne Charlies of the south. As such, the local factions began to concentrate on taking whatever they could from their hometowns. As in London, industry and invention had spread, but the proceeds of this were unjustly distributed. The working man was still on a pittance, while his employer or Member of Parliament was publicly rolling in clover.

By the time the 1860s arrived, Sheffield was no longer providing men to extort and intimidate in the name of the north. The city itself was beginning to find itself under the threat of its own local gangs, who worked their own particular neighbourhoods, offering protection in return for extortionate fees, and making the lives of those who refused to pay a misery.

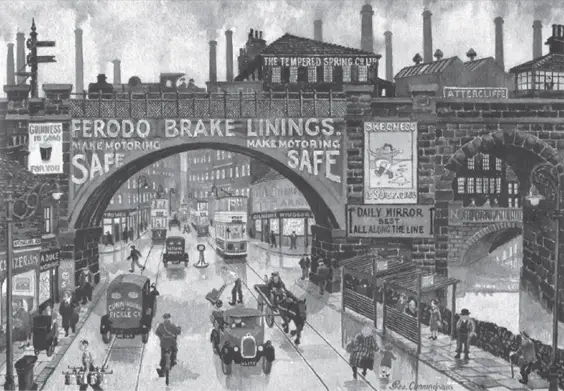

An artist’s depiction of the area of Attercliffe where William ‘Jock’ Plommer lived and died. Painted by George Cunningham

image courtesy of ourbroomhall.org.uk

“Prestige and honour”

The first two major gangs in Sheffield had very different rationales when choosing their prey. One chose to stalk the streets of the slums, keen to control their fellow working-class residents, and controlling the local businesses with violence and intimidation, whilst the other set their sights higher, and spent their days targeting the wealthier residents of the city.

The Guttapercha Gang was named after a resin used in some manufacturing processes. It was a gum which could be coated upon an object in order for it to solidify and create a rock hard coating; just the thing needed to cover a short piece of wood in order to create an effective cosh! This particular gang would patrol the slums of the workers, demanding protection money from the shops and pubs in the area. Such was their number, that the fledgling police reportedly refused to attend in situations where the gang were suspected to be involved, leaving the poor of the city to live in fear and misery.

One notable former member of the gang was infamous killer Charlie Peace, who took something of an honorary role amongst the younger men, using his reputation and criminal cunning to act as a kind of Fagin figure to the inexperienced thugs. It is also believed that Peace was the man who introduced the gang to the resin that spawned their unusual name, as he had often used this to create false appendages with which to hide his damaged and deformed hand.

In terms of prestige and honour, the Guttapercha Gang were very much at the bottom of the heap in this corner of South Yorkshire. Their practices of robbing from the poor were looked down on by every other criminal element of the city, and it was not long before the residents of the slums decided that enough was enough, and organised themselves in opposition to the gang. With their reign of fear over the slums quickly disappearing, and the rest of the city under the control of either the police or rival gangs, the death knell was rapidly approaching for the Guttapercha Gang, whose members would eventually slink back to their everyday lives, ridiculed and humiliated by those who had once been held in the shadow of a hastily manufactured cosh.

“Thorn in the side of police”

The other main gang in operation at the time was led by a well-known character who went by the name of Kingy Broadhead. Their main stomping ground was the lower end of the Park district, where the new train station was situated, and several upmarket establishments began to crop up to cater for the travelling gentry. Much of their ethos was to be a constant thorn in the side of the police who were tasked with protecting the wealthier inhabitants of the city, and it is a well-known and comical fact that nothing made the gang happier than one of their number knocking the top hat from a gentleman with a well-aimed stone!

Yet, the gang did have a darker side, and while the majority of the miscreants were causing chaos outside the station, others would stalk the platforms, demanding money with menaces whilst the police dealt with the childish acts of their colleagues. This was a well thought out and successful ploy, which kept Kingy Broadhead and his men active for over a decade before the gang disbanded due to dwindling numbers.

Later came the gangs of the east end, who held this side of the city in their hands during the post First World War years. The first such gang to emerge was the Neepsend Gas Tank Gang, which thrived in the dimly lit and often unprotected streets of Neepsend and Shalesmoor, which was the natural route home for many of the city’s industrial workers. Their methods were crude, and amounted to nothing more than robbing the returning steelworkers and miners at knifepoint. One cannot doubt that some serious money was made in this way, but their tenure as the resident east end gang was soon ended by the emergence of two much more organised and motivated groups.

“Loved a scrap”

The Red Silk and White Silk Gangs had once been one and the same, but had split due to some quarrel between themselves. Both operated in the east end of the city, and before their split, had been the gang that ousted the Gas Tank boys from the area. Having separated into two factions, the residents of the area were relieved to find that it would not be long before the main aim of the rival gangs was to attack each other, leaving the people of Neepsend and Shalesmoor largely unmolested!

The Red Silk and White Silk Gangs had once been one and the same, but had split due to some quarrel between themselves. Both operated in the east end of the city, and before their split, had been the gang that ousted the Gas Tank boys from the area. Having separated into two factions, the residents of the area were relieved to find that it would not be long before the main aim of the rival gangs was to attack each other, leaving the people of Neepsend and Shalesmoor largely unmolested!

Both gangs favoured the Blonk Street fairground as their preferred territory, making their money by offering protection to the fairground workers, and picking the pockets of anyone who was unlucky enough to find themselves penned in by a crowd. However, the two former halves of the gang did have a common enemy, and when they found themselves face to face with their foe, sparks were bound to fly. The Reds and the Whites both loved a scrap with the army, and would happily join forces should they spot a number of squaddies attending the fair. This resulted in some shocking skirmishes, with the unprepared soldiers often being outnumbered by the thugs who seemed to appear from nowhere to attack them as they wandered through the fairground.

The last of the gangs to emerge worked out of the West Bar area, and were headed by a man of Irish descent whose name would be synonymous with gang culture in Sheffield; they were merely a gang of unskilled pickpockets and race track thugs at the time, but by the time the war had come and gone, there would be very few people in the city who would not have heard of the Mooney Gang.

The onset of the First World War brought with it the dissolution of the gangs, as most of the young men were of military service age, and chose to join up with their friends, rather than wait for their eventual and inevitable conscription. If nothing else, the army was offering them a wage and three meals a day. The battle for control of the city would have to wait; but by the time peace returned, there was only one gang that would reassemble.

Article taken from ‘Sheffield’s Most Notorious Gangs’ by Ben W. Johnson, published by Pen & Sword, £12.99 paperback