Yorkshire History: The Dramatic Life of Jonathan Martin, tanner

By Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

Recently, the world watched in horror as Notre Dame in Paris burst into flames, and breathed a collective sigh of relief the next morning when it was revealed that the structure of the building, and the beautiful thirteenth-century Rose windows, had miraculously survived. York Minster, which has suffered devastating fires during its long history, is testament to the fact that total renovation can be achieved.

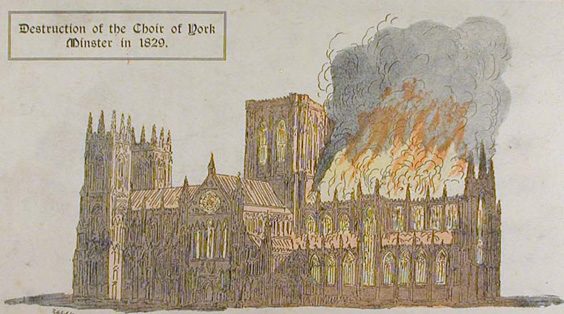

One of those fires destroyed York Minster’s Choir in 1829…

***

In a small cell, inside York Castle’s prison, a stout middle-aged man of average height and with large red bushy whiskers sat for his portrait. Jonathan Martin had become something of a cause célèbre, gaining notoriety when he attempted to raze York Minster Cathedral to the ground.

Jonathan was born 43 years earlier in Northumberland. Brought up mainly by his strict Methodist grandmother, Jonathan had a troubled childhood: ‘tongue-tied’ until he was six and cured by an operation, four years later he witnessed the death of his younger sister when she was pushed down a set of stone steps by a neighbour.

“Declared insane”

Apprenticed to a tanner, Jonathan decided that he wanted more from life. He moved to London, in search of adventure, and succeeded in his aim but not quite in the way he had planned for Jonathan was press-ganged into the navy. Britain was at war during the six years Jonathan sailed the high seas and he saw action several times. Perhaps it was no wonder, after everything he had gone through, that he began to have visions, manifested in prophetic and vivid dreams.

After leaving the navy, Jonathan returned to the north-east, married and had a son. What should have been a contented period in Jonathan’s life was brought to an abrupt end with the death of both of his parents. In search of solace but vehemently opposed to the Church of England, Jonathan embraced Methodism, becoming a Wesleyan preacher; unfortunately his mania led him to threaten to shoot the Bishop of Oxford. For this, Jonathan was arrested, declared insane and held in lunatic asylums in the north east. He was incarcerated while his wife was dying from breast cancer; after her death, even more troubled, Jonathan managed to escape.

“Mania”

Jonathan continued preaching and although the Wesleyan and Primitive Methodists shunned him, he later claimed to have converted hundreds of people. In 1826, Jonathan raised enough money to have a pamphlet he had written printed, The Life of Jonathan Martin of Darlington, tanner. For the next three years he earned his living as an itinerant tanner, hawker and fire-and-brimstone preacher. With a flair for story-telling, coupled with the many dramatic episodes of his life, Jonathan’s pamphlet proved popular and gained him local notoriety. Then, at Boston in the remote Lincolnshire fenland, something of a shotgun wedding took place: Jonathan married a local girl twenty years his junior.

Jonathan and the new Mrs Martin relocated to York and there Jonathan’s mania once again manifested itself as he railed against the Church of England. He was honest about his beliefs, indeed fully owning his dispute, leaving threatening notes in and around York Minster, with his initials and address (Jonathan lodged with a shoemaker at 60 Aldwark, about half a mile away from the Minster). Copies of his pamphlet were also distributed. Jonathan was ‘vexed to see the idolatrous worship that was going on in the Minster, and at seeing so many bad women and men walking about … the clergy drank bottles of wine and went to play-houses.’

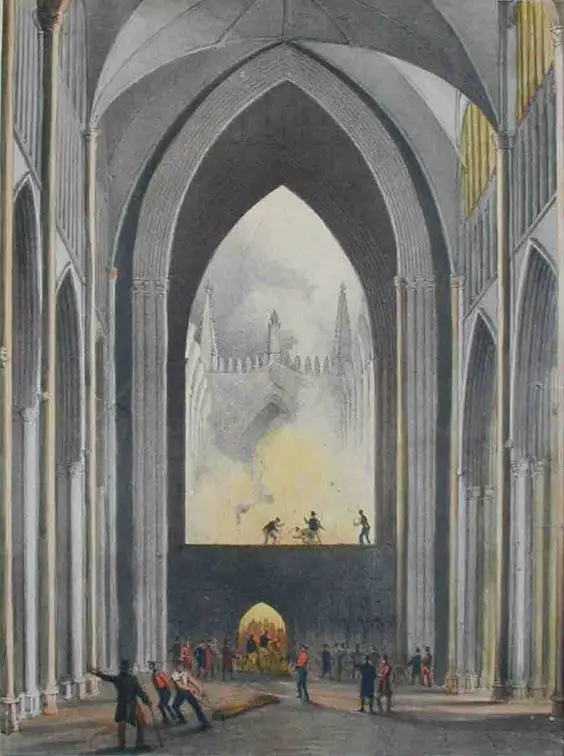

View of the interior of York Minster As it appeared immediately after the roof fell in on the Morning of the 2nd February, 1829 by John Browne

“Pray for guidance”

Matters came to a head on 1 February 1829. Jonathan could hear a buzzing noise, which was caused – he claimed – by the organ playing inside the cathedral. At 4.00 pm, Jonathan slipped into the minster for evensong, determined to stay behind when all the other worshippers had left for the evening: ‘I thought that it was merely deceiving the people, that the organ made such a noise of buzz! buzz! Says I to my sen, “I’ll have thee down tonight, thou shalt buzz no more”.’

Jonathan knew what to do, for he had been shown in a dream. He cut some rope from the bell-tower and knotted it to make a ladder, utilising his sailor’s skills. Stopping to pray for guidance from the Lord, he was told to take a bible (Jonathan knew he would go to prison for what he was about to do, and thought the book would be a comfort) and a velvet curtain, all gold tassels and fringes (to ‘make unto thyself a robe, like David the king, and put the fringe at the bottom of it’ and the tassels on his cap). Then Jonathan set about his business, building a pile of prayer books and one of cushions. Setting fire to them both, Jonathan secured his velvet finery and bible in a bundle and, as the clock struck three, slipped out of the cathedral into the icy darkness by means of his rope ladder. Turning his face northwards, Jonathan made his way out of the city.

“Model patient”

Meanwhile, it took the good citizens of York a while to realise the danger; anyone out and about in the early hours kept their heads down against the chill morning air. It was not until a choirboy slipped on the ice, fell flat on his back and looked up to see the smoke rising from the cathedral that the alarm was raised. The fire brigade came post-haste and neighbouring towns sent fire engines too, but it was evening before the fire was put out. It was perhaps scant comfort at the time, but luckily most of the minster survived and all that was lost to the fire was the choir. The finger of suspicion fell instantly on Jonathan Martin. He was captured four days later and taken to the prison at York Castle.

The subsequent trial excited interest across the country. A guilty verdict would have meant death but Jonathan was declared insane and incarcerated in the infamous Bedlam, otherwise Bethlem Hospital in London. There, Jonathan spent the rest of his days quietly, painting and behaving as a model patient as long as the topic of religion was avoided.

York Minster has survived not only Jonathan Martin’s arson attempt but a smaller accidental fire in 1840 and then the major conflagration in 1984 which engulfed the south transept (and which was most likely caused by a lightning strike). The restoration was lengthy and cost millions, but returned the Minster to its former glory. Notre Dame too will survive.

Images courtesy of York Museums Trust :: https://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk :: Public Domain

Edited and abridged article taken from ‘All Things Georgian: Tales from the Long Eighteenth-Century’ by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden, published by Pen & Sword (2019) in hardback. ISBN: 9781526744616

Top image: Portrait of Jonathan Martin by Edward Lin(d)ley, 1829