The History of Jawbone Hill, Sheffield

By Melvyn and Joan Jones

The top of Jawbone Hill lying at 816 feet above the Don valley between Grenoside and Oughtibridge affords a wonderful vantage point. To the south and south-west there are clear views over Sheffield including such easily identified landmarks as Hillsborough Stadium, the University Arts Tower, the whole of the city centre with the town hall and the two cathedrals, and beyond to the Gleadless valley, Norton Water Tower and Herdings flats.

Turning to the west and north-west is the rolling hill country between Worrall and Bolsterstone, an area of outstanding beauty in which the small stonewalled fields, winding lanes, hamlets and isolated farms and valley woodlands form a perfect complement to the natural landscape. Beyond that rises the exposed and relatively treeless plateau between Ewden Beck and the Little Don.

“Ancient parish”

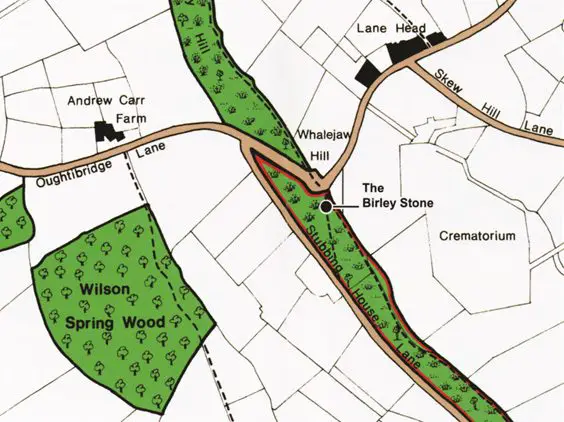

So how did Jawbone Hill, or as it is also known, Whalejaw Hill, get its name? Some accounts suggest that actual whales’ jawbones once stood at the top of the hill but there is no firm evidence for this assertion. Just as likely is that it got its name because the bend in the lane forms the perfectly symmetrical shape that would have been formed by erecting whale jawbones as an arch.

At the top of Jawbone Hill there is also an important medieval boundary stone. It was first recorded – as Burleistan – in a boundary agreement in 1161 between Richard de Lovetot, lord of the manor of Hallamshire, and the monks of the Abbey of St Wandrille in Normandy. This abbey had been granted land in the ancient parish of Ecclesfield and monks from the abbey had founded Ecclesfield Priory by 1273. In the boundary agreement, the monks were to have the freedom to pasture their flocks of sheep and cattle from January to August in a great wood that covered the valley side as far as the Doun (the River Don) from Wereldsend (Wardsend) to Uhtinabrigg (Oughtibridge).

“Disused quarries”

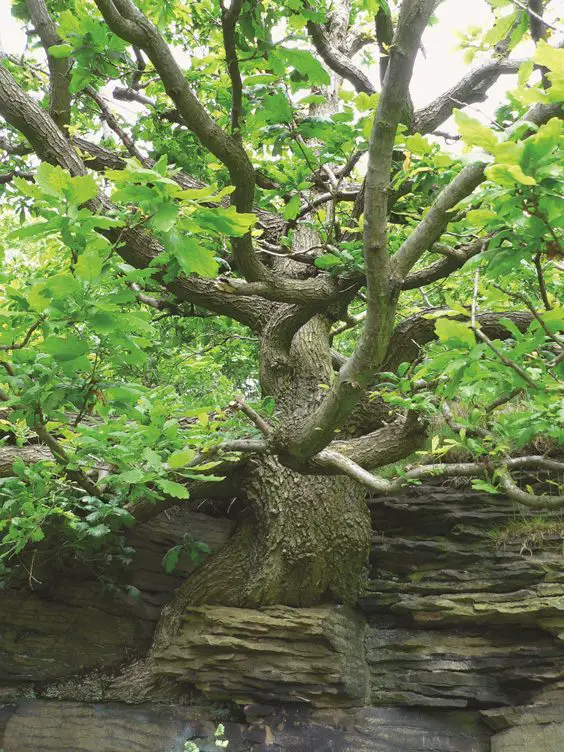

The monks were also permitted to pasture their swine (this practice was called pannage) on the fallen acorns in the same wood in the autumn. The remnants of this great wood remain as Wilson Spring Wood and Beeley Wood. The base of the stone may be the original medieval one, but the shaft is later. Indeed, the original stone may not have been a straight stone shaft, but a stone cross to mark the way from Ecclesfield to Bradfield via Oughtibridge and Worrall. In this case it probably already stood in its present position when the 1161 boundary agreement was drawn up. The stone later became a boundary marker between the Grenofirth and Southey quarters of Ecclesfield parish. Birley Stone and the surrounding area is part of the Pennine ‘stone country’.

On a short walk to the south along the footpath towards Back Edge outcrops of rock abound and soon the path is diverted by mounds of soil and rock waste from disused quarries. And everywhere are dry stone walls dividing one field from another. This is because the long slope from Birley Edge down to the River Don is underlain by thin seams of coal inter-bedded with shales and massive beds of coal measure sandstones – Greenmor Rock, Grenoside Sandstone and Penistone Flags.

“War effort”

The Second World War also made its temporary mark on the landscape at the top of Jawbone Hill. The area to the east of the Birley Stone, now occupied largely by the crematorium, was an ammunition depot with the ammunition hidden underground in grass-covered bunkers. Here were stored the bombs used in raids on Hitler’s Germany and taken on a regular basis by convoys of lorries to the airfields in Lincolnshire. All that is left to remind us of this important part of the war effort are a number of marker stones showing the boundary of the site.

There is, immediately behind the Birley Stone, on the edge of the copse, a boundary stone with the initials W D (War Department) on the far side. Beside the Birley Stone stands the Festival Stone, so called because it was erected by Wortley Rural District Council (Grenoside until 1974 was not part of the City of Sheffield) to celebrate the Festival of Britain in 1951. This is topped by what has variously been called a ‘topograph’, or a ‘toposcope’, which is a display showing the direction and distance from the stone of natural and built landmarks.

Article taken from ‘A-Z of Sheffield’ by Melvyn and Joan Jones, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445681832

Article taken from ‘A-Z of Sheffield’ by Melvyn and Joan Jones, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445681832

I read a few years ago that there was an excavation of the area and remains of the whale’s bones were unearthed, I can’t remember where I read this.