Carlton Colliery – A Welsh Mining Community in Yorkshire

By Melvyn Jones

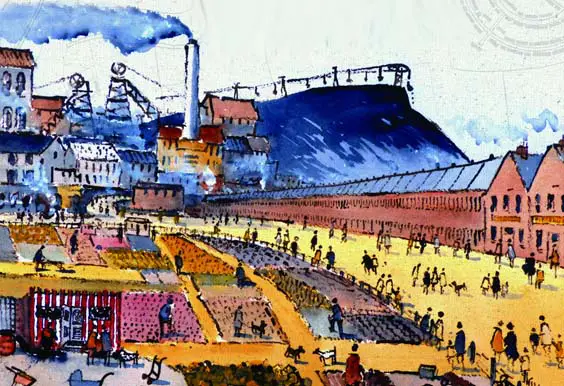

Carlton had two collieries, both of which had eventful histories. In 1870 Joshua Willey from Hoyland leased land from the Earl of Wharncliffe and sank two shafts of what he called Willey New Colliery to the south-west of the village north of Carlton Road down to the Woodmoor Seam at the shallow depth of only 40 yards. Within just a year or two Willey sold the colliery and a new colliery company was formed called the Wharncliffe Woodmoor Coal Company.

The company intended to operate from four shafts exploiting in addition to the Woodmoor Seam, the Two Foot Seam and the Winter Seam. The colliery changed hands twice again during the 1880s. From the 1890s coke ovens were in operation and in the twentieth century four more seams were exploited: the Beamshaw, High Hazel, Kent’s Thick and Lidgett. For most of its life the colliery was known as Wharncliffe Woodmoor 1, 2 & 3 or Old Carlton. It closed in 1966.

Steep drift mine

While old Carlton Colliery was in its very early years another colliery was being sunk to the east of the village, almost halfway between Carlton and Cudworth by the Yorkshire & Derbyshire Coal & Iron Company. As in the case Old Colliery the colliery was on land belonging to the Earl of Wharncliffe who cut the first sod on 12 November 1873. Originally it was called Carlton Main Colliery. The colliery was closed between 1910 and 1924, and when it re-opened it was renamed Wharncliffe Woodmoor 4 & 5, but was always locally known as New Carlton. In later years a steep drift mine was made to reach the deepest workings. Altogether five seams were exploited at the colliery. It closed in 1970.

The presence of two collieries on either side of the village had a major impact on its population growth, its attraction to migrants and the way that the layout of the village changed. At the beginning of the Victorian period, Carlton was a rural village with a population of little over 400 in 1841. Between 1841 and 1871 the population declined so that by 1871 it stood still at 380. Things changed with the opening of the two collieries.

Intriguing

The pre-mining village was in the form of a main thoroughfare (Royston Lane) with two back lanes, Chapel Lane and Spring Lane, winding away to the west behind it before joining to become Carlton Road. From this nucleus during its time as a mining village, Carlton grew, slowly in all directions, the result of both infilling and outward extensions. By about 1930, sixty years after the sinking of Old Carlton Colliery, there were ribbon-like extensions along Carlton Road beside the colliery, being called, not surprisingly, Willey Row; along Shaw Lane in the direction of New Carlton Colliery; and at the junction of Fish Dam Lane and Mill Hill Lane to the south of the village, known locally as ‘Sticky Top’.

There was also a sizeable adjunct to the north-west of the old village between Crookes Lane and Wood Lane dominated by Grays Road and Briggs Street. Infills included allotment gardens, a village pub, a miners’ welfare recreation ground, a Methodist chapel ad a new parish church with its distinctive saddleback roof built at the expense of the Ear of Wharncliffe. The new parish of Carlton had been carved out of the much larger parish of Royston in 1879.

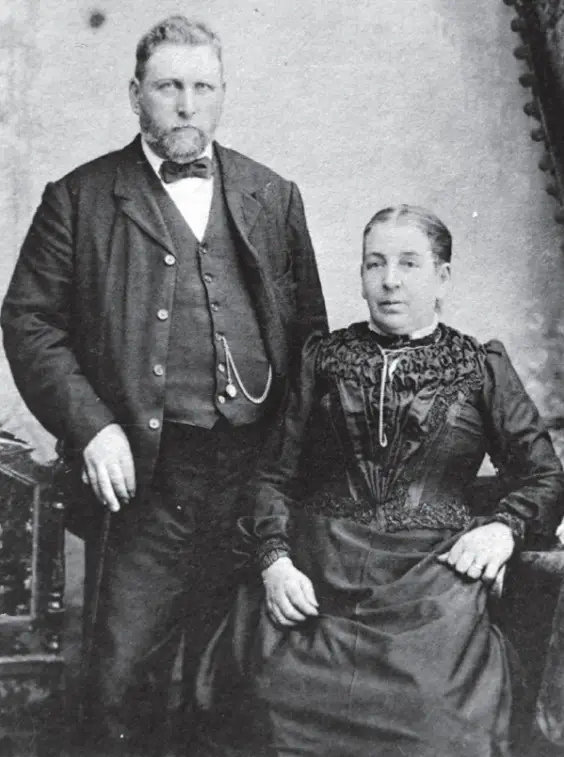

But the most intriguing infills of all were built by a Welshman of very high standing living in the village. This was Evan Parry, a migrant from north Wales and manager of the Old Carlton Colliery from 1884 to 1911. The appointment of Evan Parry sparked off an important long-distance migration that gave Carlton a distinctive character. Towards the end of the nineteenth century the village of Carlton had become known locally as ‘Little Wales’. Its population included 38 families containing nearly 200 people headed by a Welsh-born man employed in coal mining.

Impact

The story of this migration begins in the small industrial community of Mostyn in the parish of Whitford on the Welsh side of the Dee estuary in the summer of 1884. At a time the main colliery extended under the estuary for more than half a mile and on 19 July 1884 water from the estuary broke into the mine and flooded the workings.

The Flintshire Observer reported on 24 July 1884 that the ‘disastrous occurrence’ was ‘of the most serious nature for the whole district, as no less than two hundred men and boys have been thrown out of employment’. On 31 July 1884, the same newspaper, under the headline ‘The Calamity at Mostyn Colliery’ reported that despite continuous pumping since the flooding, the water level in the pit had not yet fallen. It soon became apparent that it was unlikely ever to be operational again. And that indeed was to be the case.

The impact on the community was devastating. Whole families were suddenly without a regular wage and shopkeepers and other businesses soon began to feel the effect of mass unemployment and then the population decline set in as people began to leave the district to seek work elsewhere. Heads of families began to move, often leaving their families in Mostyn and returning at weekends or once a month. When it became increasingly clear that there was little or no hope of Mostyn Quay Colliery ever opening again, the women, with their children, let to join their husbands and older sons in the places where they had found regular colliery work.

Guidance

Although some of the migrants to England and beyond settled in places as diverse as Manchester, Liverpool and Melton Mowbray in England, and Patagonia, Buenos Aires and Alabama in the Americas, most miners and their families went to a restricted number of places, particularly in south Lancashire, and remained in coal mining. It has been reported that some of the miners took their pit ponies with them to Lancashire, but the ponies would only obey orders given in Welsh!

Some of the migrants made their way to the villages of Carlton and Smithies. The connection between Mostyn and South Yorkshire was, of course, Evan Parry, a native of Mostyn was appointed manager of Wharncliffe Woodmoor 1,2 and 3 (‘Old Carlton’) Colliery at Carlton in 1884. Without his appointment the Welsh colony would not have come into existence and without his continued guidance, encouragement and commitment it would not have evolved as it did.

Besides Parry’s immediate family, other close relatives were important members of the emerging Welsh colony. Both his younger sisters followed their elder brother to Carlton – Anne and her husband Evan Williams and their four children arrived sometime between 1885-91; Catherine and her husband David Davies had also arrived by 1890. Both of Evan Parry’s younger brothers also followed him to South Yorkshire. The youngest brother, Enoch, and his family seem to have arrived in the district in about 1888. Evan’s older brother David, who was unmarried in 1891, was lodging with his sister Anne at the time of the census in that year.

Driving force

Other pioneering families from the Mostyn area living in Carlton by 1891 were those headed by Richard and Elizabeth Jones, Thomas and Sarah Hodgson, Edward and Elizabeth Macdonald and Thomas and Sarah Edwards. In the neighbouring village of Smithies, where David Davies, Enoch Parry and Evan Williams and their families lived, other pioneering families were those headed by Owen and Ann Jones, John and Isabella Jones and John Gittins, a widower in 1891.

Besides these families there were also thirteen lodgers from the Mostyn area listed in the 1891 census. One of these lodgers, David Parry, has already been mentioned. Three others are worthy of notice. David Jones Williams, then in his mid-twenties, was commercial manager at Wharncliffe Woodmoor Colliery where Evan Parry was manager. He was later to rise up and become secretary of the colliery company and then a director. Ithel Macdonald and Thomas Cunnah were both young men (19 and 21 respectively). They were to be major driving forces in the building of the Welsh Chapel in Carlton.

Census

At the time of the 1891 and 1901 censuses, the Welsh colonists were dispersed widely in Carlton and the neighbouring village of Smithies, a reflection of the need for migrants from north Wales to rent housing or take lodgings wherever they happened to be available. There was even one family that had originated in Mostyn living in Westgate in Monk Bretton in 1901. This family headed by John Williams, shows the pull that guaranteed work and life among your own kind had on former miners at Mostyn Quay Colliery, causing a very round-about migration. It is known that John Williams went first to Hanley in Staffordshire where he married. The 1901 census shows that his youngest three children were all born in Carlton, but his three oldest children, all boys, were born in Argentina!

The early 1890s witnessed developments that were to create a physical and cultural focus for the Welsh community in Carlton. Again Evan Parry, the colliery manager, was a prime mover. In 1891 he purchased a partly built house, Brookfield House, on Chapel Lane at Carlton, together with two parcels of land on either side of the lane. By 1901 he had converted Brookfield House into three separate dwellings and built 22 new houses including what are known today as Greenfield Cottages, Southfield Cottages, Gordon Villas, Providence View and Brookfield Terrace. By the time of the 1911 census there were 25 families, 124 people in all, living in this small residential enclave. All but one of the 25 heads of household was in an occupation connected with Old Carlton Colliery. The exception was a police constable.

Providence View (left) and Brookfield Terrace (right), Carlton, two of the seven groups of cottages built at Evan Parry’s expense

Migration

The inhabitants included Evan Parry, by that time retired, his wife, three sons (two of whom were hewers and the eldest a certified colliery manager) and seven other families with a Welsh-born head of household. In one of there families, although the husband and wife, Thomas and Esther Jones , had both been born in Flintshire, three of their four children had been born in Golborne in Lancashire, one of the known Lancashire destinations of the migrant miners from Mostyn Colliery. So the Joneses had taken part in a stepwise migration. A resident in Brookfield Cottages had been born in Staffordshire, but his wife was from Flintshire as were his two sons, suggesting that he had perhaps migrated from the West Midlands to Wales and then back again to England following the Mostyn Colliery disaster.

As these developments, catering for the physical comforts of the rapidly growing mining community, including member of Evan Parry’s family and other key colliery employees were taking place, moves were also afoot to provide for the spiritual needs of the Welsh population. In 1890 it was decided to create a church where, as their pastor was to describe it a few years later, they could ‘worship the God of their fathers in their native tongue’. A Welsh church, in the sense of a group of people sharing the same beliefs and worshipping together, was founded in the summer of 1890. The congregation continued to meet in people’s homes or rented rooms for the rest of the decade.

Church choir

At the beginning of 1901, the Reverend Menai Francis, pastor of the church, called a meeting of the senior members of the church to look into the possibility of building a chapel at Carlton. In May 1901, the Earl of Wharncliffe’s agent, together with Evan Parry, met the Building Fund Committee in Carlton with a view to selecting a possible site. This was fixed in Carlton Lane adjacent to the land Evan Parry had bought about ten years earlier and on which he had been busy building houses. Subsequently a lease of thirty years was agreed at a rent of 5/- a year. The contract for building the chapel was put in the hands of Walkers of Sheffield who specialised in building corrugated iron buildings including chapels. The chapel was opened on 6 June 1902. It had cost £200 to build.

The Welsh chapel at Carlton shortly before its demolition in 1984 and (inset), a close-up of the chapel sign in Welsh

Money to build, furnish and maintain the chapel came from many sources. There were generous donations from members and friends and from the profits from musical concerts. There has been a church choir since 1895 and concerts were given in the Public Hall in Barnsley. It was also the custom from the early days for the choir at Christmas to go round Carlton and to some of the bog houses in Barnsley, ending up at Rhydwen, the house of David Jones Williams. After performing carols and Welsh hymns they were given refreshments by the Williams family.

Strong allegiance

The period between the opening of the Chapel in 1902 and the beginning of the First World War in 1914 was the high point in the life of the community. By that time the Anglo-Welsh community must have been several hundred strong (estimates vary from 200-400). Even if individuals or families were not chapel-goers, they had the opportunity to attend the regular events that took place that reminded them of their origins and reinforced their cultural identity.

In this period there was still a trickle of in-migrants from North Wales, children of the original migrants had grown up, married and had young families, and many first and second generation members had a strong allegiance to the chapel. The Welsh language was still used in the home as well as at chapel, and occasion such as carol singing around the village at Christmas time, Whitsuntide outings, musical concerts in Barnsley, and the annual singing festival (gymanfa ganu) with other West-Riding Welsh chapels (Sheffield, Leeds and later Doncaster) and Welsh societies, had become regular events.

In this period there was still a trickle of in-migrants from North Wales, children of the original migrants had grown up, married and had young families, and many first and second generation members had a strong allegiance to the chapel. The Welsh language was still used in the home as well as at chapel, and occasion such as carol singing around the village at Christmas time, Whitsuntide outings, musical concerts in Barnsley, and the annual singing festival (gymanfa ganu) with other West-Riding Welsh chapels (Sheffield, Leeds and later Doncaster) and Welsh societies, had become regular events.

Although marriages took place between members of the Welsh community or between member of the Welsh community and partners from Wales, marriages also occurred between members of the original migrant community and partners from local families or from families who had migrated to Carlton at much the same time as the Welsh community was being formed there. One of the Evan Parry’s sons married a girl from north Wales but the others chose marriage partners from South Yorkshire of English stock.

Generations

The contribution made by Evan Parry in sustaining the community in its early years cannot be overestimated. He provided employment and housing (although his cottages were by no means exclusively occupied by Welsh families) and he arranged a temporary home for the church congregation on Sundays between 1894 and 1902. As manager of the Old Carlton Pit, he rearranged shifts so that the church choir could give concerts and no doubt helped in many other ways.

After the First World War, the attrition of the community identity went on relentlessly through marrying out. In some families this happened in one generation. Despite the fact that assimilation was taking place at a rapid rate, the Welsh Chapel continued to prosper in the inter-war period and during the Second World War, fortified periodically by migrants from Wales to the Barnsley district. The annual Gymanfa continued till the early 1980s, but by that time chapel membership was less than 20 with no more than a dozen attenders, services were held only intermittently, and the building was demolished in 1984. There must be hundreds of people still living in the Barnsley area descended from these Welsh in-migrants. Gwen Bright, for example, mayor of Barnsley in 1978-79, was the grand-daughter of Evan Parry’s sister.

‘South Yorkshire Mining Villages: A History of the Region’s Former Coal Mining Communities’ by Melvyn Jones is published by Pen & Sword Books, £14.99, ISBN: 9781473880771

Top image by Martin Clark, used under CC License (CC by 2.0), Re-claimed land near Carlton. This land south-east of the former coal mining village of Carlton, South Yorkshire, has been re-claimed and landscaped after coal spoil tipping in the area from Carlton Main Colliery. Looking south towards the glass works at Monk Bretton.

I have lived in the village all my life and remember both pits well, my dad working at 3/4 colliery and remember going with my dad to pick his wage up on friday when i was off school. I also worked at wooley colliery for 24 yr and married a cunnah,and still live on wood lane. AND PLEASE CAN SOMEBODY TELL ME WHY THEY CALL IT ATHERSLEY MEMORIAL PARK . NO COLLIERYS WERE IN ATHERSLEY.

Evan Parry is the brother of my gt. grandmother Catherine Davies (nee Parry) (Nain Davies) and I was baptised in Salem Chapel, December 1940. Thank you very much for this article. How I enjoyed reading about my families past.

My grandfather Gilbert Stanley Robinson worked at the Wharncliffe woodmoor colliery in 1941. He worked the no5 pit. My father grew up in Cudworth. I’ve been looking through some of my grandfather’s mining books and this is how I discovered he worked at the pit no5.

I was interested to read that John Williams had lived in Hanley. I am researching the Welsh in North Staffordshire & will try to locate him but he has a very common Welsh name. If there any further information on John?

I loved reading that. Just wish there was more about Carlton because I grew up there in the late 60’s into the late 1980s.

We were a well known family name