Jewel of the North: The Birth of Saltburn-by-the-Sea

By Colin Wilkinson

One afternoon in the summer of 1859, Henry Pease was staying at Cliff House, his brother’s villa in Marske, when he disappeared. He returned late and explained to his wife that he had walked along to Saltburn where a few fishermen’s cottages met the sea and ‘seated on the hill-side he had seen, in a sort of prophetic vision, on the cliff before him a town rise’. This is a romantic version of the conception of a new town which hides the hard business motives for its development.

The family’s investment at Middlesbrough, through their holding in the Owners of the Middlesbrough Estate, had been attractive and this could be another opportunity. There was also the potential to increase revenue from passenger services on the railway being extended to serve the ironstone mines beyond Redcar. The land at Saltburn belonged to Lord Zetland and Henry had to find out if he would sell. G. D. Trotter, Lord Zetland’s land agent, was approached. He made enquiries and wrote ‘there is every reason to suppose that Lord Zetland will be desirous to afford every facility in his power to promote the object you mention at Saltburn’.

“Stakeholders”

Henry was able to gather a group of investors who were known to him from other ventures such as the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR), the development of Middlesbrough and industrial projects to join him in investing in the Saltburn Improvement Company. These included Henry’s brother John and his nephew, Joseph Whitwell Pease. There was Isaac Wilson, who had arrived in Middlesbrough in the 1840s to work in the Middlesbrough Pottery. He went on to become a maintenance manager for the S&DR, and later formed, with Edgar Gilkes, the engineering works of Gilkes, Wilson & Co. Also among the stakeholders were Thomas MacKay, the secretary of the S&DR, and Arthur Kitching, whose fortunes had changed when his ironmongers shop in Darlington supplied some nails to the S&DR, and from there the business had grown to build locomotives and carriages.

A few years earlier, Alfred Kitching and Thomas MacKay had been amongst those who, along with Henry Pease, had formed the South Durham Iron Works in Darlington. With this support Henry was able to develop his dream and create a new resort. Land was bought from Lord Zetland, initially only 10 acres, but the option for more was agreed. However, the need for more land would suggest the project was becoming successful, and Lord Zetland would also benefit from the price per acre increasing. The Saltburn Improvement Company’s land sale records show that £30,385 was spent buying land. The first row of houses was started in 1861 at Alpha Place, followed by the streets named after gems. Was this to become the jewel of the north?

“Intoxicating”

Meanwhile, the railway arrived. The first passenger service to Saltburn started in August 1861 and, as there was no accommodation yet for visitors, it was promoted as an opportunity for those on holiday in Redcar to take the fifteen-minute journey to survey the splendid views of coast and country from the lofty cliffs. This seems to have worked as 6,000 people used the route in the first six weeks of operation. Of course, more passengers would use the railway if hotels were built, and here was another opportunity for the S&DR.

The grand Zetland Hotel was designed by William Peachey, an architect working for the railway who was also responsible for the Royal Station Hotel in York. When construction of the hotel was announced at a meeting of the railway’s shareholders, not all thought this was a good move. One shareholder, a man from Guisborough, complained it was a ‘very bad speculation … it is a nasty, bleak, cold place and the sand is hard’. Another suggested that intoxicating liquor should not be sold in the hotel, but despite this and the Quaker representation amongst the railway ownership and their support of temperance, there was little backing for this idea and commercial necessity triumphed. There was luxury and comfort for visitors in the large coffee and dining rooms, the spacious reading room, billiard room and smoking room.

Joseph Toyn, president of the Cleveland Miners’ Association, once had his office and home in Saltburn’s Ruby Street.

“Canopied streets”

Opened in 1872 and branching from the line to Saltburn across this grand viaduct over the Skelton Beck, the railway was extended towards Skelton and the ironstone mines.

The Saltburn Improvement Company controlled the authorisation of building plans to ensure the resort was not spoilt. There was a requirement that the white bricks produced by the Pease brickworks at Crook be used on the façade of buildings. Only the fronts of houses or shops could face the street, while warehouses and workshops had to be well away from the street frontage. Among the trades prohibited were soap boilers, tripe men, curriers, candle makers, fell mongers and blacksmiths. All streets were to be properly paved with flagged stones.

Opened in 1872 and branching from the line to Saltburn across this grand viaduct over the Skelton Beck, the railway was extended towards Skelton and the ironstone mines.

Visitors were catered for in the shops along the canopied streets including confectioners, a silk mercer and a jet merchant, dealing in this fashionable jewellery. During the nineteenth century, rings, bracelets and necklaces made from this black gem became popular, with demand increasing on the death of a public figure – Queen Victoria’s wearing of jet after the death of Prince Albert provided a major boost. The valley gardens had been set out, overlooked by the classical entrance portico brought from the station at Barnard Castle.

The ‘immense’ Zetland Hotel was opened in 1863, although one shareholder in the Stockton and Darlington Railway questioned spending £8,000 on the building.

“Hedonistic”

Hidden in a quiet spot was a spring which provided the spa water that so many resorts boasted. Taking the waters was, like sea bathing, promoted as having health benefits. A resort that could advertise mineral waters increased the chances of attracting visitors. A source was found at Saltburn, and an analysis of the water produced in 1864 revealed that it had the same qualities as the famous spa water at Harrogate. Not surprisingly, in this district there was a trace of iron.

Opened in 1872 and branching from the line to Saltburn across this grand viaduct over the Skelton Beck, the railway was extended towards Skelton and the ironstone mines.

This was advertised as a key component in the water along with chloride of sodium, which would stimulate the gastric juices and so make the digestion of the iron into the ‘general system of circulation’ and help with any condition involving ‘poverty of the blood’. Leading from the gardens, according to one visitor, the walk led to ‘romantic woods as far as Skelton and its castle. . . . ‘the birthplace of a lofty, illustrious line of nobles and the ancient cradle and nursery of warriors, princes and kings . . . and above all Robert de Brus’.

New houses were springing up around the town with some available to rent for the holiday season. Henry Pease, seeing his dream come true, sought a house there as a summer retreat and in 1865 he was offered a house in Britannia Terrace for £1,650. His wife recalled they spent three or four weeks in Saltburn almost every summer, forming a very happy part of the children’s holidays with ‘the fine sands for driving or walking, the boating and fishing and listening to bands in the gardens’. Did You Know? A Hell Fire Club at Skelton? During the eighteenth century, clubs appeared around the country, organised by wealthy men seeking to shock with their pursuit of hedonistic pleasure. The most notorious was the Hell Fire Club of Sir Francis Dashwood at Medmenham Abbey. By this time, Skelton Castle was the home of John Hall Stephenson, who nicknamed it the Crazy Castle. From there, John ran the Demoniacs Club and brought together a group of gentry and clergy for days spent playing sports outdoors and drinking and talking by night. Members included local landowners, army officers and Laurence Sterne, the author of the bawdy The Life and Times of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

The Alexandra Hotel provided competition for the Zetland Hotel, although both are now converted to apartments.

Competition for the Zetland Hotel appeared in 1867 when the Alexandra was built for John Anderson, an engineer on the S&DR. However, apart from the gardens and the beach there was little to amuse visitors, and from his hotel, Anderson took the lead in providing another attraction. A pier had been suggested in the early days of the resort development; however it was John who held a meeting in October 1867 to discuss the pier and the funding of the £6,000 that would be needed to pay for the construction. It was to be 1,500 feet long, made from iron piles and supports and timber decking, with shops at the entrance and a saloon at the head. The pier opened in 1869.

“Great wave”

“Great wave”

The early years were successful: in 1870 the shareholders who had bought £5 shares to pay for the build received a dividend of 10 per cent. The success of this venture perhaps encouraged the building of the two piers at Redcar and Coatham; however, like these, the sea would show its force at Saltburn. In October 1875, the pier head and landing stage were washed away. Repairs were made but the pier was shortened by 250 feet leaving the iron piles of the isolated section standing alone in the sea and in need of removal. This brought a representative of the Nobel’s Explosives Co. to demonstrate the power of dynamite. Nobel had patented the manufacture of dynamite in Britain during the 1860s – it was a new high explosive that used nitroglycerine. Unfortunately, nitroglycerine had the disadvantage of being known to explode spontaneously, which did little to encourage its use. Nobel managed to find a way of preventing this but there was still reluctance to use his explosive. Saltburn provided a chance to demonstrate its powers and superiority over gunpowder. Charges were placed out at sea and when detonated those watching from the clifftop saw a great wave of water thrown 40 feet into the air.

The town being on the clifftop brought comments from visitors that it was ‘such a tiring place’ and to go down to the pier and beach involved ‘a certain amount of unpleasant jarring’. To make this easier a hoist was built in 1870. This was not a facility to be used by those fearful of heights as it involved walking out over the cliffs along a gangway to the hoist which was lowered vertically down the 120-foot drop to the pier entrance. The descent could be nerve-wracking – sometimes the mechanism stuck halfway down. By 1883 the hoist was considered to be unsafe, and it was replaced with the cliff lift that is still in use.

“Impact”

Another high-rise construction was the bridge above the valley gardens. It removed the need to tackle another climb and descent to make the trip from Saltburn to Skelton and beyond. This was the Ha’ Penny Bridge named after the toll charge of 1/2d for a pedestrian to cross – the toll could rise to 6d for a carriage drawn by four horses. However, the main drive to build the bridge was to open up the land across the valley from Saltburn for development, but builders were not attracted. The bridge was built by Gilkes, Wilson and Co. and during the construction in 1869 disaster struck. Three workmen were stood at the top of a pillar, some 100 feet above ground, waiting to manoeuvre a girder that was being pushed across from the completed section of the bridge, when it fell, struck the pillar, and sent the men crashing to the ground.

The Ha’ Penny Bridge was used for an early trial of a telephone system. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell made a call on his first working telephone and a new age of communications was launched. He was in England in August 1876 demonstrating his latest version of his invention to a group of scientists in Plymouth. In the same month H. A. Irving was laying a wire across Saltburn’s Ha’ Penny Bridge connecting telephones to the homes of Sir Francis Fox and Judge William Ayrton. Irving had heard of Bell’s work and had developed similar equipment to use on this trial. Francis Fox, who was director of Bell Brothers Iron Masters, was so impressed that he arranged to extend the trial over a longer distance. To do this he had a telephone installed at the company’s offices at the ironstone mine at Brotton and at the head office in Zetland Street, Middlesbrough. For much of the way the telephone link used the telegraph poles that stood along the railway line. Perhaps Saltburn can claim to have the first telephone system in the country.

The impact of the economic depression that developed during the 1870s has already been seen in the strike and reduction in wages paid to the ironstone miners. There were much wider consequences; the downturn produced what one commentator called the ‘terrible calamity that has overtaken the district’. Iron works were operating at a loss and eventually there were failures. By 1879 Gilkes and Hopkins and Co. were unable to continue trading, as were Messrs Lloyd and Co., another firm with blast furnaces.

“Driving spirit”

The management of both firms included Isaac Wilson and Edgar Gilkes who were also involved with the Saltburn Improvement Co. With so much difficulty in the manufacturing sector, the enthusiasm for the development of a seaside resort faltered. Then in 1881 Henry Pease died, taking away the driving spirit behind the development. His wife recorded that he felt ‘a shade disappointed as years went on that Saltburn did not grow as rapidly as at first it seemed to promise to do’. Saltburn was left looking for new leadership. This came from the Saltburn Extension Co. formed by a group which included the owner of the Middlesbrough Gazette.

Some housing continued to be built and as the nineteenth century faded the town had a range of houses for sale; a villa with three reception rooms, ten bedrooms, billiard room, cloak rooms, butcher’s pantry, kitchens, conservatory, and motor house was on sale at £7,000. At the other end of the scale terraced houses with a bathroom could be bought for £330. By 1901 Saltburn had a population of 2,578, of which 58 per cent were female. This was above the national average – no doubt the domestic work available in the grand houses and hotels coupled with the opportunity that widows had taken to run lodging houses to earn a living there contributed to this imbalance.

Above the glen at Saltburn is Rushpool Hall, built with ironstone from the Skelton mine in 1864 for John Bell, a member of the family of industrialists Bell Brothers.

“Orchestra”

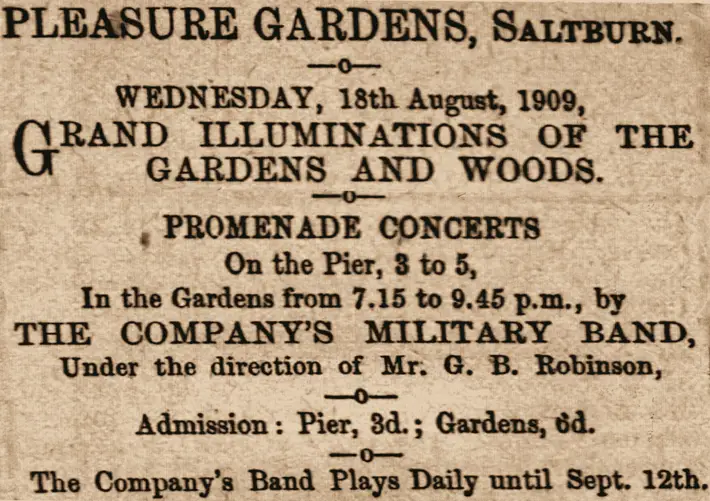

As the twentieth century arrived, attractions had been developed. The Assembly Hall had been built in 1884 and, between performances by touring companies, dances were held. There were brine baths with swimming lessons available in the 75 x 10-foot pool. Moving pictures were being shown in 1909. Easter 1909 saw the start of celebrations to welcome visitors at the start of the season. In the Valley Gardens, the 5th Lancers band were booked to provide concerts, a display was organised by Brocks fireworks, and Japanese lanterns would light up the gardens. Afternoons could be spent listening to the town’s orchestra.

For holidaymakers, there was varied accommodation. A semi-detached villa with three reception rooms and six bedrooms was available during August of 1905 for 8 guineas per week. The Alexandra Hotel advertised rooms starting at 8/-(40p) per day, with a superior room with sitting room and bedroom available for 13/6 (67p). Breakfast was 2/-(10p), hot lunch was 3/6 (17p), and dinner was 5/-(25p). During the afternoon, tea with cakes was served at a price of 1/6 (7p). The Zetland had the luxury of having its own railway platform where trains pulled in from the main station.

“Opportunities”

“Opportunities”

Visitors to the Zetland Hotel did not need to use Saltburn station as trains would pull into the hotel’s own platform. This was the Tower School at Saltburn which offered ‘thorough modern education for girls’ and provided opportunities for sport including tennis and sea swimming.

In the early years, the new Saltburn was not all about a holiday resort. Among the lodging house keepers, bathing machine proprietors, waitresses, tailors, plumbers and railway workers living in the town were quarrymen and miners. Deposits of ironstone were close by at Hob Hill, and by 1865 these deposits were being mined and quarried by the Pease business. In 1872, it was being reported that the bulk of the ore had been taken out, and by early 1875 the mine was closed.

Article taken from ‘Secret Redcar, Marske and Saltburn’ by Colin Wilkinson, published by Amberley Publishing, £15.99 paperback