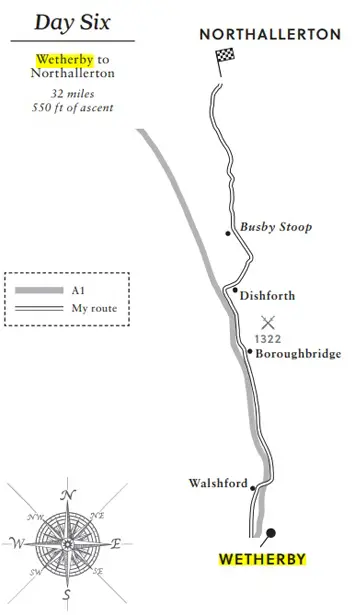

Cycling the Great North Road – Wetherby to Northallerton

By Steve Silk

I sleep fitfully at a thoroughly underwhelming Airbnb on the outskirts of Wetherby. The bed linen clearly hasn’t been washed, there are no proper curtains at the window and missing slats cause my mattress to sag. In fact the whole experience had been off-putting from the start. Via the app, the householder had warned me that he wouldn’t be there, but a key would be left out. So, the previous night, I had let myself in to this perfect stranger’s house, leant the bike against the banisters and tiptoed upstairs to the spare bedroom. In the dead of night I awake from a dream in which a burglar had tried to get in, rattling the front door as he did so. When I finally give up on sleep at about 7am, I discover that the dream had been real. My host has unexpectedly returned in the early hours but is unable to let himself in because of a dodgy door latch. He has since come back for a second time and is waiting patiently outside. I let him back into his own house and we exchange awkward pleasantries in the kitchen. He’s very polite about being locked out, I’m too cowardly to tell him what I think of his facilities. In summary, I can’t get out quickly enough.

Wetherby, understandably on a Sunday, has yet to wake up. Only Costa Coffee is open for business, but I’m far from being the first customer. The place is swarming with cyclists out for the obligatory Sunday run. Bloody part-timers. For the first time since Look Mum No Hands, I actually fit in because everyone is noisily clip-clopping around in cleated shoes whilst wolfing down cake and coffee. Most are doing west-east journeys so their miles will be hillier and harder won than mine. Other than that, I don’t get beyond a few gruff acknowledgements. Within the cycling fraternity of Yorkshire a solemn “how do?” goes a long way at this hour.

Back on the road, I cycle back past Sant’ Angelo and head up the Deighton Road. Whilst The Angel used to claim it was halfway between London and Edinburgh, the actual spot is a mile or so to the north at Kirk Deighton. Here, outside a pub called The Old Fox, Harper tells us that the “milestone told the same tale on either face”. This was a big deal for the drovers who would celebrate with a ritual drink – even though they were unlikely to have come all the way from Edinburgh. Both the pub and the milestone are long gone, though I like to think the latter lies in someone’s garden. In my utopian future where the Great North Road becomes a cycling superhighway, The Old Fox would rise again as The Halfway House – a bike hostel for long-distance cyclists. They could even include beds with a full complement of slats.

Back on the road, I cycle back past Sant’ Angelo and head up the Deighton Road. Whilst The Angel used to claim it was halfway between London and Edinburgh, the actual spot is a mile or so to the north at Kirk Deighton. Here, outside a pub called The Old Fox, Harper tells us that the “milestone told the same tale on either face”. This was a big deal for the drovers who would celebrate with a ritual drink – even though they were unlikely to have come all the way from Edinburgh. Both the pub and the milestone are long gone, though I like to think the latter lies in someone’s garden. In my utopian future where the Great North Road becomes a cycling superhighway, The Old Fox would rise again as The Halfway House – a bike hostel for long-distance cyclists. They could even include beds with a full complement of slats.

“Quick breather”

I spend ten minutes scrabbling around in the undergrowth, hunting for the remains of the old building – it’s becoming rather a habit on this journey. I convince myself I’m in the right place, but maybe it’s just wishful thinking. In the planning of the trip, I’d promised myself a drink here in honour of the drovers. But it’s 8.30 on a Sunday morning so that pledge is quietly jettisoned as I continue along the Great North Road in its new guise as the A168. To my surprise, there’s a semi-official bike path running alongside. Judging by the paint markings poking out from beneath the weeds, I really am on the original road. And as a bonus, there’s a thick hedge of tumbling May blossom between me and the traffic. It’s so secluded that I stop for no other reason than to enjoy the solitude – easy like Sunday morning. Rather guiltily, I run my eye around the geometry of the bike. Before I set off, I’d resolved to clean it daily. Well, that just hasn’t happened. I’ve yet to have a puncture, the pressure on both tyres feel fine to my touch and the unfashionably long mud guards really are protecting every other surface. This bike is proving to be admirably low maintenance. I also pay attention for the first time to some steel knitting needles attached to the chainstay. I faintly recall the patter from the salesman. “If you’re stuck in Darkest Peru, and you buckle your wheel, there will be always be someone who can fix it as long as you’ve got spare spokes.” Ah, yes, spokes.

This path keeps me out of trouble as far as Walshford, where the Great North Road crosses another Yorkshire Dales river, the Nidd following hard on the heels of the Wharfe at Wetherby. From now until the Scottish border, you feel the presence of the Pennines even if you don’t often see them, as river after river takes its turn to cross the GNR on its way to the North Sea. I’m old enough to have had the I-Spy books as a kid. How about a Great North Road version complete with a list of rivers, as well as coaching inns and battle sites?

The hamlet of Walshford has been bypassed not once but twice over the years so that three northbound roads now lie almost side by side. The oldest has a parkland estate to one side and a collection of buildings belonging to The Bridge Inn on the other. In the old days it traded on its proximity to the main road, to a certain extent that still holds true, but now a bit of quiet doesn’t go amiss as it enjoys its latest incarnation as a “hotel and spa”. Here, you don’t need much of an imagination to feel the centuries fall away and see the mail coaches clatter through. The old road likes to throw in a cameo appearance like this from time to time; – always in unfashionable spots and only if you know what you are looking for. Leaning against the bike, I’m caught day-dreaming on this theme by a hotel worker coming out for a crafty fag, his very presence embarrassing me back into activity.

After Walshford my road switches to the east of the A1, becoming straight and without sanctuary for the cyclist. The odd car speeds past at 60 mph; a reminder that it’s good to get these miles done on a Sunday. Back at Alconbury in Cambridgeshire, I realised that the settlements were getting fewer and further between. This section of road takes thatconcept to the next level. I feel, if not lonely, then alone for thefirst time. The road has passed through the M62 population belt and I won’t go through another major conurbation until Darlington, some 50 miles to the north. Further on, I stop for a quick breather next to another of the cast iron mileposts that I’m growing rather fond of.

“Managed to retain its original footprint”

Raising my head from the road, I realise that two of England’s national parks are now visible – one on either side. To the west, the spine of the Yorkshire Dales, little more than a water colour of dark blue on the horizon. To the East the closer, more distinct outline of the North York Moors, a trick of the light making its smoother contours much clearer. In an instant it becomes crystal clear why the Great North Road takes this route. The A1, the A19, the A167 and the East Coast railway line all share the relatively flat Vale of York. Surely as long as Brits have travelled north and south, this has been where we have channelled our major highways.

Then it’s Boroughbridge, a market town which has grown in recent years so that there are substantial outskirts to plough through first. Before the town centre I take a short detour to see the three mysterious standing stones known as the Devil’s Arrows. No-one can really explain their purpose although some mention a connection with a southernmost summer moonrise. Aligned north-north-west to south-south-east, the Bronze Age giants are between 18 and 22 feet high, the latter taller than anything at Stonehenge. A fourth stone is said to have been removed in the late seventeenth century as Boroughbridge endured a brief phase of Philistinism. In the words of the mapmaker William Camden it “was lately pulled downe by some that hope, though in vaine, to find treasure”. No treasure, but still some grandeur. Although it’s a grandeur despite the setting, rather than because of it. You can’t help but be disappointed to discover that two of the three stones are behind a fenced-in field of cabbages while the third is marooned the other side of a minor road. Surely they have to be brought together within a park setting?

All told it’s not surprising that local historian Ronald Walker has described the arrows as being “among theleast understood and most neglected historic monumentin Britain”.

Boroughbridge breaks the Great North Road mould by keeping its High Street hidden from the main drag. Only the coaching inns were on this thoroughfare, but they were at the centre of an unlikely hub. Making my journey from London to Edinburgh, I’m inclined to forget that there were other coaches heading for other destinations. The North Briton, The Phoenix, The Diligence, The Expedition and The Defence all ran from Leeds to Newcastle via Boroughbridge; The North Star went from Leeds to Edinburgh; the Rapid from Harrogate to Thirsk and the Union from London to Newcastle. Finally, the Royal Charlotte from Leeds timed its services to meet both Newcastle and Glasgow coaches in this otherwise inconsequential town. The Crown was at the centre of the web. It’s another classic coaching inn which has managed to retain its original footprint. I once stayed here on a cold February evening when snow fell unexpectedly during the night. Cars were banished, twentyfirst century sights and sounds disappeared under a cloak of white and were it not for the presenter of Stray FM reading out the school closures, we might have been enjoying our bacon and eggs in Dickensian times. It was wonderful in every way.

“Old ghosts”

But this time I don’t even stop for a courtesy coffee, heading instead for the bridge over the River Ure – site of the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322. Like Empingham back in Rutland, this battle took place directly on the Great North Road. The Earl of Lancaster, rebelling against Edward II, was caught in a pincer movement between the king heading up from the south and a force led by Sir Andrew Harclay coming down from the north. Harclay’s men blocked both the bridge and a nearby ford. Lancaster tasked the Earl of Hereford with taking the bridge. But, in an incident worthy of Horrible Histories, Hereford was killed by a pikeman hidden under the bridge who managed to thrust his spear directly up Hereford’s backside. It wasn’t a great omen. Many more men were killed before Lancaster managed to negotiate a truce. And even that proved short-lived. He was later beheaded at Pontefract Castle, with 30 of his followers punished in the same way.

Immediately to the north of the bridge, the Great North Road traffic used to turn right. Nowadays we turn left because the old route lies obliterated under the runway of Dishforth Airfield. The full irony only becomes clear as I cycle along its western perimeter a few miles later. In recent years the airfield itself has become obsolete with weeds poking up through the concrete. So an abandoned Great North Road now lies under an abandoned Second World War airstrip. Perhaps I was paying too much attention to old ghosts here, because the next thing I know I’m on a dual carriageway heading for Thirsk. At Junction 49 it’s easily done. For a scary mile and a half I survive on a hard shoulder before re-joining the original Great North Road at Topcliffe which surprises me by calling its High Street “Front Street”. To me, Front Streets belong to the north east of England, preferably County Durham. Topcliffe is very much in North Yorkshire, but the road sign suggests I am making good progress. I remember the village for another reason too. While I exercised the MAMIL’s Godgiven right to do slightly geeky leg stretches against the Methodist church railings, I see my first swifts of the summer screeching overhead. “Aye, they’ve been here a few days now,” says a neighbour, “Where are you heading?” “Northallerton – and I’m starving.” “Northallerton? Get yourself down the carvery at The Golden Lion. You canna go wrong.” Summer’s here, the swifts have arrived and there’s decent food down the road. Excellent.

Somewhere around here the traveller leaves the Vale of York for the Vale of Mowbray – and crossing the River Swale at Topcliffe feels as appropriate a boundary as any other. While the Vale of York is seen as an area of intensive arable farming, the Vale of Mowbray has a more intimate scale. One gets the impression that while the tourists head for the high ground of the Dales and the Moors, the locals here are happy to get on with their farming out of the limelight.

To the west of the Swale, the modern A1 temporarily follows the line of Dere Street – the Roman road which ran from York to Scotland through places like Catterick, Bishop Auckland and Corbridge. Running north-west rather than north, it is nevertheless dead straight. Meanwhile the original Great North Road stays to the east of the Swale and looks almost entirely unmodernised as I cycle on. “The remaining 19 miles to Northallerton scarce call for detailed description,” wrote Harper.

“Story kept growing”

I have to disagree. The first junction of note is a roundabout with a petrol garage on one side, an Indian restaurant on the other and an unusual name on the map: Busby Stoop. Behind those two words lies a grisly folktale dating back more than 300 years. The restaurant was, until very recently, a pub. And in 1702 the landlord was Thomas Busby, a small-time criminal who had married Elizabeth Auty, the daughter of the notorious counterfeiter Daniel Auty of Danotty Hall. Father and son-in-law initially got on well, but later fell out. And one day when Busby returned to his pub the worse for wear, he found Auty sitting in his favourite chair threatening to take Elizabeth back home. There are numerous versions of what happened next, but the most succinct summary I’ve found comes from journalist Chris Lloyd in a feature for The Northern Echo newspaper:

“Thomas ejected Daniel from both chair and pub and later that night crept into the counterfeiter’s house and bludgeoned him to death with a hammer. Busby was found guilty of murder and forgery and ordered to be hanged on a gibbet to be erected on the crossroads outside the pub, his body having been first dipped in tar to prolong its decomposition. Before the execution, Thomas was allowed a final drink in his favourite chair. As he left for the hangman’s noose, he cursed the chair, saying anyone who sat in it would suffer a premature, painful end.”

Curiously, the tale then takes a 200-odd year breather before a chimney sweep sat in the chair in 1894 and was found hanging from the original post (or stoop) the next day. But the legend really took off during the Second World War when the pub – already renamed The Busby Stoop – became popular with Canadian airmen based at nearby RAF Skipton-on-Swale. Locals said that RCAF aircrew who sat in the chair never came back from their bombing missions. From then on the story kept growing.

Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s there appeared to be a rash of strange tragedies. And when a young builder died after being cajoled into sitting in the chair by his mates, the landlord Tony Earnshaw banished it to the cellar. The final straw came when a delivery man tried it out down there – and died in a road accident soon afterwards. In 1978 Earnshaw donated the accursed chair to a museum in the nearby town of Thirsk – with strict instructions that no-one should sit in it. Busby’s chair is now to be found at the community-run Thirsk Museum. Until relatively recently, it was rather hidden away, suspended from the ceiling in the kitchen section, a little out of sight, out of mind. But in 2018 it was moved to pride of place in the front room – hung high on a wall. Crucially no-one is allowed to sit on the chair – not even the Japanese film crew who had travelled thousands of miles thinking they could do just that. I visited the museum once and couldn’t resist asking the volunteer guide if, really, it wasn’t a load of old nonsense. “Well, most of those deaths do seem to be coincidental,” she said. Then she fixed me with a rather beadier eye. “But on the other hand, there do seem to have been rather a lot of them.” I paused, not knowing whether to push the point. “Put it like this,” she continued. “Last winter when it came off those hooks I was happy to polish it, but silly as it sounds, I certainly didn’t sit on it.”

I cycle on through Sandhutton, shadowing the River Wiske northwards. Looking at the OS map, I spot Danotty Hall Farm. It still exists, it seems. So I find myself turning left, crossing the river at tiny Kirby Wiske and heading off down narrow lanes. Eventually I get a look at the farmhouse, but it lies at least half a mile off-road, perched on a hill top. It was this lonely location which helped Auty evade justice as a counterfeiter for so long. I can see why. But the track is too rough and too long for a random bit of cold-calling by a bloke on a bike. Reluctantly, I turn back for the main road.

“Earned the right to be here”

“Earned the right to be here”

A few miles later I arrive in Northallerton which announces itself as the prosperous capital of North Yorkshire with a broad High Street and a wide range of shops. It’s oldfashioned enough to allow drivers to park directly on the street, but new-fangled enough to have delicatessens and expensive cafés. On a weekday it demands to be described as “bustling”. There’s a traditional department store, a foodie shop seemingly modelled on Fortnum & Mason and the first bookshop I’ve seen since Highgate.

As I get closer to the centre, I finally articulate a feeling that’s been bubbling up for a while. Stamford, Newark, Wetherby and now Northallerton, these are all places I’ve visited before. But now I’m seeing them through different eyes – simply because I am arriving under my own steam. Digging deep into an O-level French vocabulary, I remember the verb “gagner”. Gagner – to reach, to earn, to win. I’ve not just reached Northallerton, I feel as if I’ve earned the right to be here. This is going to sound ridiculous to anyone who hasn’t cycled long-distance, but towns really do feel bigger and better if you’ve had to crack on through the countryside and the hinterland under your own steam.

The substantial frontage of The Golden Lion dominates the High Street. And in case anyone needs reminding of the inn’s name, a porch projects onto the pavement complete with fluted Doric columns below and a large statue of a lion above. I like the place from the minute I walk through the door. It’s a busy, friendly hotel, clearly at the heart of the community. Back in Lincolnshire I raved about The George at Stamford. Clearly that place values its heritage, but perhaps its owners also see the hotel as a tourist attraction in its own right. There’s none of that self-consciousness at The Golden Lion, just a stream of people passing through with the help of cheerful staff. Something about it screams “lazy Sunday” at me. So I spontaneously award myself a half-day off and decide to stay the night. My bike gets locked away next to the boiler, the pannier gets dumped in the room and it’s straight to the Sunday roast – which is perhaps even better than the man in Topcliffe had predicted.

Once run by the now defunct hotel chain Trust House Forte, The Golden Lion was taken over by George and Greta Crow in 1998. Difficult as it is to believe, the couple had no experience of hotels, having previously made a living in the world of travelling fairgrounds. But with three young children to look after, they were keen to put down roots. More than 20 years on, the hotel has flourished under genuinely local ownership. And now, two of those three children are running the place. Daughters Allanda and Scarlett are joint managers, although one gets the impression that both mum and dad put a hand on the tiller from time to time. I sit down opposite Allanda on a leather sofa in a timeless bar directly overlooking the Great North Road. My view is dominated by fireplaces and wooden doors with polished brass handles. I know they’re polished because I’ve already seen the lady out with the Brasso.

“In keeping with its history”

Tradition runs through this place like a stick of rock. “Northallerton is a market town and we’re a really important part of it,” she says, in a soft North Yorkshire accent that, to my Southern ear, has hin ts of Teesside in it too. “You could almost say we’re the heart and soul of the place. So what we do, well it’s got to be in keeping with its history. “We keep updating things of course. But,” and here she gives an involuntary shudder, “we just couldn’t do supermodern”. Please don’t. The fabric of the building dates back to 1730, but the old well shaft, glassed over in the bar, is taken as evidence of an older building on the same site. In the coaching days there was enough stabling for 75 horses – indeed some of the buildings survive to the rear. “Horses on the ground floor, stable hands directly above,” advises history-loving Dee on reception. During the Second World War it was well-used by aircrew based at nearby RAF Leeming. Among them, the No 427 (Lion) squadron from the Royal Canadian Air Force. Some of its crew couldn’t believe their luck when they saw the name of the pub. So when Northallerton awoke one day to find its statue missing, it didn’t take a genius to work out who might have scaled the building to bag a new mascot. We’re told that after the police made “an urgent but discreet call”, the lion reappeared. It’s stayed there ever since.

In the afternoon I take to Waterstone’s for a browse in the local history section. But even that feels wrong – much as Dave and Sue’s living room felt wrong in Lincolnshire. It’s what I do in my “normal” life, not this nomadic one. Still, I now have enough Ordnance Surveys to take me well into Northumberland. Delaying gratification, I wait till I’ve secured one of the Golden Lion’s many sofas before lovingly un-concertina-ing them. I do feel sorry for people who don’t understand that a map is there to be read just as much as a novel.

Later still, I wander up the High Street – to find that civil war characters continue to stalk me. The Porch House, now a B&B, is the oldest property in town. According to local legend it was visited twice by King Charles I – once as a guest in 1640 and then again as a prisoner in 1647. This was when the Scots were in the process of selling him back to Parliament, allowing the B&B’s website to claim that “it was through the Porch Door that the constitutional monarchy came into being and the absolute monarchy was left behind in history”. I walk a little further and have a quick pint in The Standard pub, a friendly local where everyone greets one another by saying “Now Then” – even when they answer the mobile. There’s a happy, beery fuzz about the place, but we’re all running out of weekend. Some of us have got to work, others of us have got to push pedals. I down my drink and walk back to my room from where I can see the shiny mane of the golden lion reflecting the street lamps. I don’t feel remotely guilty about that half-day. Northallerton, you’ve been magnificent.

‘The Great North Road: London to Edinburgh – 11 Days, 2 Wheels and 1 Ancient Highway’ by Steve Silk (Summersdale) is available from all good retailers: https://amzn.to/3dcHDEO