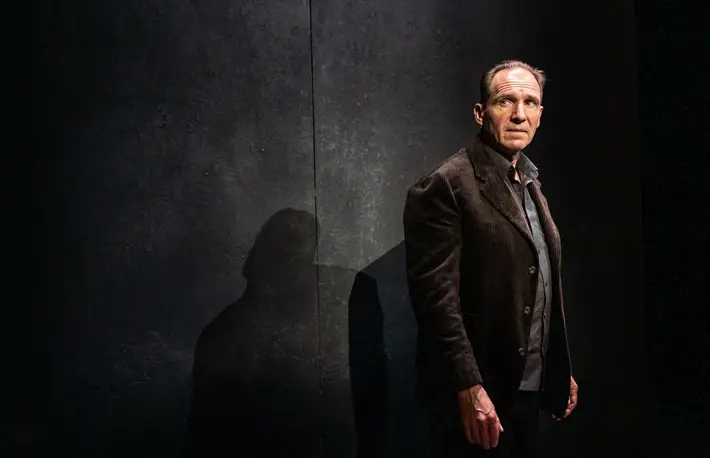

An Interview with Ralph Fiennes

Ralph Fiennes directs and stars in a world premiere adaptation of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets to welcome audiences back to live theatre. Compelling, moving and symphonic, Four Quartets offers four interwoven meditations on the nature of time, faith, and the quest for spiritual enlightenment.

Mostly written during WWII when the closure of playhouses during the Blitz interrupted Eliot’s work in theatre, the four parts (Burnt Norton, East Coker, The Dry Salvages and Little Gidding) were the culminating achievement of Eliot’s Nobel Prize winning literary career.

Here, he talks to writer and critic Michael Davies about verse, versatility and Voldemort.

MD: Where did the idea for doing Four Quartets come from?

RF: I’ve known it since I was quite young – we had the TS Eliot recording – so it’s something that’s been floating in and out of my awareness over the years. In the first lockdown last year I gave myself little things to engage my mind and memory, and I thought I’d learn Four Quartets. And then various things I thought I’d do the early part of this year went away – films and so on – and it sort of transitioned. Could it not be put in a context where it was not just recited in a suit or something, but given a kind of gently, appropriately judged theatrical context?

What happened next?

I was daunted and excited in equal measure by what it might be, but with the help of my agent Simon Beresford, [creative producer] James Dacre got behind it and liked the idea. Then the Eliot estate got behind it and then a lot of very talented people in theatre production were available – like Hildegard Bechtler, Chris Shutt and Tim Lutkin, all brilliant in their field. I’m a great believer in the energies of things signalling whether they’re meant to happen or not, so it seemed that the cumulative gathering of people being available and wanting to be part of it sent me a sign that this had some viability.

Why does Four Quartets appeal to you?

I think it deals with such endless essential perennial questions of time, the spirit, the soul, the journey of the soul in life – big, big ideas. In the end you could say the takeaway is “Live in the present” but he goes deeply into how we’re trapped in notions of sequential time. But it’s a very human quest by a man who I think has been through the wringer internally himself – questioning his existence, very unhappy marriage, sense of identity – and then the war crystallising this sense of quest. So it’s endlessly mysterious, but I think there are also ways of speaking it that are conversational and accessible.

“It continues to communicate”

How much is Eliot’s voice in your head?

Not much at all. I said to the team on our first day of rehearsal back in February that I thought we should all listen to Eliot’s recording – the master’s voice – but we all came away with a very strong sense that this was not helpful for us if we want to make this accessible. It’s an old-school delivery with a certain kind of refined English intellectual speaking: it has its own kind of beauty and it’s wonderful to hear his voice but the dynamic of its communicative ability more for younger people today I think is questionable, because it feels from another time. I want the poem to communicate to younger minds; I want it to be active.

Four Quartets was written in the 1930s and 40s, when the world was in crisis. How strong is the resonance with today?

Very strong. We’re trapped in our houses, we’re denied all these norms of social interaction, assumptions about life and work and travel are all taken away, and so I sense we’re left with: what are we, who am I, what is of value in my life, in our shared lives? It continues to be a crisis of what we don’t know, where this thing is going. And Eliot references a sense of where we have to embrace not knowing: “And what you do not know is the only thing you know.” Doing it for colleagues and friends in rehearsal, one of the key and most common responses was: “My God, it’s so modern – my God, it’s all about now.” And that was a very frequent response to it.

What do you hope this interpretation will achieve?

I want to enable the poem to be heard. Eliot has not been a focus in the theatre for a while. In his writing there is a religiosity, or questions of faith, which perhaps is unfashionable. I love Eliot’s poetry: I think it continues to communicate and I think often great writers suffer from the zeitgeist or the vogue of the moment and get relegated and forgotten about. I have a belief that the poem can work and I think it does chime with the big questions or the existential questions that I think we are asking about who we are – and I think that’s thrown into focus by the Covid crisis.

“Sense of intimacy”

Tell me more about how the production came together.

Simon Beresford, my agent, proposed James as a producer. I didn’t know James but from one conversation with him on Zoom I immediately felt comfortable with his deep sensitivity to the material. He was totally supportive and I felt his excitement about what it could be. A very basic stepping stone is that your collaborators believe in the thing that you are attempting – that’s what I got from James, followed quickly by Danny Moar at Bath.

Why have you decided to take the performance to regional theatres?

That was part of the proposition. First of all I just said, “Can we do this?” Then Simon and James said, “What about doing it as a regional tour, to offer it to regional theatres who may be excited to be able to open their theatres with this?” And that appealed to me. It appealed to me to not do it in London, just purely to have the experience of going to different cities. That excited me because it’s different – I’ve not done it and I’m very aware that there are committed theatre audiences all over the country, so it was a bit of a no-brainer. I love the idea of being on the road: it’s rather romantic.

Why have you chosen these theatres?

I was very protective of the sense of intimacy. In some theatres we’re not selling the very top circle because I wanted to keep the sense of intimacy and didn’t want to have to go into the level of projected voice, where there are certain nuances and delicacies that often get diluted. The poem has to feel like a conversation. I remember going on stage and doing a bit for Danny and saying, “Can you hear? Is it working?” It was just putting my toe in the water as to how it felt in the theatre because it’s all very well walking the paths of Suffolk, where I am, doing it to the sheep but the thing is, how will it land?

“You can just feel the crackle”

You’ve had huge success in both film and theatre. Do you have a preference?

I love the very simple thing that you walk on to a space, either a monologue in this case, or with other actors, and you start something and you create immediately. Even as I get older, the simple essential magic or possibility of that is endlessly fascinating – so simple and so profound at the same time. Film is full of huge potential thrills in terms of what the end experience can be for an audience but the process of film-making is not actor-friendly really. But then you might say, surely in front of a theatre audience you don’t have the chance to do it again? No you don’t, but there is a dynamic of contact with an audience so you’re in a dialogue with the people receiving it. I suppose the short answer to your question is, I think I’m more at home in the process of theatre.

Your career has covered everything from the Bard to Bond. Do those jobs feel different in your head, or is it all just acting?

It is a sort of truism that good writing is always attractive, whether it’s classical or modern writing. You can just feel the crackle. I think I’ve got any actor’s hunger as to what’s a good part where there’s human complexity, there’s dramatic impact. We all like to be challenged and stretched.

Is it true that villains are more fun?

In a kind of basic way. They’re not fun if they haven’t got any complexity to them. Actually one of the challenges of Voldemort is that he was mostly just sheer, distilled evil – the point of Voldemort is that he doesn’t have a conscience – and that was quite a challenge because there was no doubt or inner contradiction. What puts the full stop on Richard III being a great part is his sense of regret or fear about what’s he’s done, and suddenly you have this other colour – doubt – and then he puts the lid on it. So that stuff is great. If there’s endless degrees of grey, I think that’s really human.