The History of The Grand Hotel, Scarborough

By George Sheeran

A prospectus for the construction of The Grand Hotel in Scarborough was published in 1862 by the Cliff Hotel Company. Squabbling among the board of directors, however, and the failure of the original building contractor, led to the hotel’s completion being delayed until 1867. Its architect was Cuthbert Brodrick, who created what is arguably the most accomplished Second Empire design of hotel in Britain, yet it has been continually misinterpreted. To begin with, the architectural press did not approve.

The Building News commented that Brodrick’s drawing of the hotel, which wasn exhibited at the Royal Academy’s exhibition in 1867, displayed four domes that looked like ‘roe’s eggs’, and that the ‘rest of the building is of ordinary hotel character’; The Architect considered it ‘architecturally speaking, a failure’.18 Local myths have also arisen that are similarly wide of the mark, portraying Brodrick as creating an allegory of time and patriotism: four domes (the seasons), twelvem storeys, 365 rooms; V-shaped in honour of Queen Victoria; the largest hotel in Europe. Both contemporary critics and local historians have misconstrued Brodrick’s design. Newspaper reports of the opening agree that there were around 350 rooms. At this capacity it was then the largest hotel in England, but them largest in Europe was probably the Grand Hotel, Paris, 1861–62, with 800 rooms.

“A pleasant residence all year round”

Yet the Scarborough Grand is an extraordinary building and Paris is the key to its design. While some contemporary critics seem convinced that the Grand was designed in an Italianate style, classical French architecture, and in particular the reconstruction of Paris by Napoleon III seems the fundamental influence. What Brodrick produced was an imposing Parisian block with corner towers and domes relocated to the northeast coast of England. In the treatment of the roofline in particular, the greatest homage to France is paid. Four domes mark the ends of the two ranges.

The corner towers are sumptuously finished above the eaves with sculptural embellishment incorporating marine creatures and foliage together with classical masks. Atlantes (male figures) dressed in lion skins support pediments, while flanking the south-west and southeast of the apex we find caryatids (female figures). The caryatids here are in the form of the seasons, perhaps reflecting the directors’ claim that Scarborough offered a pleasant residence all year round, for ‘the season at Scarborough has been for some years extending into the autumn and winter months’. The Grand’s sculpture seems to have been executed by the Leeds firm of sculptors Burstall and Taylor.

There was more to the hotel than its uncompromising appearance. The interior was fitted with the latest technology: service hoists, an ‘ascending room’ (lift for guests), electric bells from guests’ rooms to reception, speaking tubes connecting each floor with reception or the manager’s office, a telegraph, and so on. The drawing room, with views across the bay, was lit by four gas standards in the form of bronze statues rising from ottomans. In the provision of food also the Grand would appear to have scored well above its rivals. Its boast was that the dining room could accommodate 500, and its kitchens had been equipped with some fastidiousness.

Above left: The sculptural embellishment above the eaves is spectacular. Here, four female figures (caryatids) in the form of the seasons support a richly decorated pediment above one of the windows.

Above right: While here and along the sides male figures dressed in lion skins (Atlantes) are employed.

“Fashionable”

From its opening the Grand was presided over by Augustus Fricour, former manager of the Hotel Mirabeau, Paris, who had also been consulted on the fitting of these kitchens. Here was a further factor that set such hotels apart: improved standards of food and a rising interest in cuisine. Yet this did not please everyone. While staying at the Grand Hotel, Scarborough, around 1890, the poet and travel writer Percy Tunnicliff Cowley seems to have been discomposed by the Continental air of the Grand. The waiters were either ‘German, French, or Danish’, and the food French:

“sat down to dinner á la Francaise, and enjoyed it. I say enjoyed; but I am bound to admit I very strongly object to a French cuisine … When you have entrees dished up with sauce this and sauce that á la Francaise, I defy any ordinary Englishman to come up with an accurate idea of what he is eating … Why cannot we have our English food served up in the good old English fashion?”

The Grand Hotel should be recognised for what it represented. It was among a group of internationally important hotels that emerged in the 1850s and 1860s in capital cities and fashionable watering places, and whether this were London or Paris, Brighton, Baden or Lucerne, such hotels courted and catered for the demands of a wealthy international elite.

Later Years

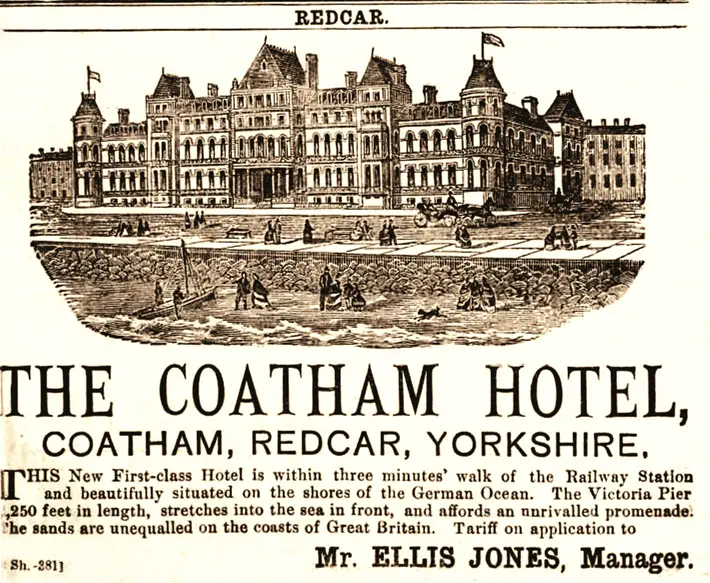

During the 1870s and 1880s the pace of hotel building seems to have slackened, and nothing was built to compare with the grand hotels brought into being in the1860s. This may have had its origins in recession in the textile and iron industries in the 1870s; some areas of agricultural production also declined. Perhaps this was the reason, for instance, why one of the few grand hotels to be built in this decade – the Coatham Hotel at Coatham – was seemingly never completed, its east wing remaining unfinished at its opening in 1872, although the proprietor was still advertising an image of its originally intended form as late as 1877.

The building of grand hotels did not resume until the 1890s, yet even then some schemes failed to come to fruition, such as the development of the southm of Bridlington Quay. This included a hotel, but it did not materialise, and the sitem was sold to the Leeds contractors, Whitaker Brothers. That firm, however, was to play a significant role in the building of two other hotels. The first is an odd one in that the hotel planned for the new resort of Ravenscar survives to this day, but the resort itself failed. Plans were in train by 1896 to convert the older Peak or Raven Hall into a hotel. The architect Frank Tugwell did this by linking a large new hotel building to Raven Hall on its north side, in a classical design which was probably thought to harmonise with the older building. The new hotel was advertised as being open at the end of December in 1896 and ‘furnished throughout like a comfortable country house’.22 Whitakers seem to have been the contractors for both this and the Hotel Metropole in nearby Whitby. The latter was described as ‘recently erected’ by them in a public offering of shares advertised widely inthe press in July 1898. Several of the directors – Walter R. S. Pyman or James mSharphouse Moss – were local shipowners and it seems likely that a syndicate of northern businessmen and Whitaker Brothers were responsible. The architects were Chorley and Connon of Leeds who produced a design difficult to categorise.

The Coatham Hotel, Coatham, from Bradshaw’s Railway Guide, 1877 (Charles John Adam). It was proposed to add the wings after the central body was completed

“Notable”

Its form is a block four storeys high, but with corner towers rising to five storeys and ending in pyramid roofs. In the centres of the north and east faces there are shallow towers ending in curvilinear gables. Whether one likes this architectural style or not, the Whitby Metropole makes a spectacular contribution to the West Cliff. When it opened in summer, 1898, it offered ‘Suites with Private Bathrooms, 100 Bed-rooms. Electric Light, Passenger Lift’.23 It probably also brought Whitby more to the attention of the well-heeled as a holiday destination, with one advertisement even comparing the place to the Swiss mountains – ‘Fashionable Whitby. The Engadine of England’.

Certainly the Metropole attracted some fashionable and notable visitors. As visitor lists at the end of the century show, guests came from across Britain as well as from other parts of the world, such as Europe and America. They comprised numbers of aristocracy plus elite commercial and industrial families, its most honoured guest being probably HRH the Maharajah of Cooch Behar and his servants.

Hotel Metropole, Whitby (Chorley and Connon, c. 1898). The design may have been influenced by Alfred Waterhouse’s Hotel Metropole, Brighton.

“Meticulous service”

These were the last of the luxury hotels to be built on the Yorkshire coast, and, along with some smaller but select ones, they continued to function as such until the beginning of the twentieth century and later. By then several had been absorbed into hotel groups.

The Hudson Hotels Company, for example, owned the Crescent at Filey, the Crown at Scarborough and Raven Hall; Hotel Metropole at Whitby became part of the Frederick Hotels Company, Frederick Gordon being one of the outstanding hotel entrepreneurs of the nineteenth century owning luxury hotels in both England and Europe. Lodging houses and small hotels continued to be built throughout the nineteenth century, supplying accommodation to the many thousands of visitors to the county’s coastal resorts, but they operated on a different level, and offered little competition. This was in part a result of scale, in part standards of service. Setting was a further decisive factor. The Grand at Scarborough, the Alexandra at Bridlington Quay, the Zetland at Saltburn and the Metropole at Whitby could all provide meticulous service in superior locations.

The Hudson Hotels Company, for example, owned the Crescent at Filey, the Crown at Scarborough and Raven Hall; Hotel Metropole at Whitby became part of the Frederick Hotels Company, Frederick Gordon being one of the outstanding hotel entrepreneurs of the nineteenth century owning luxury hotels in both England and Europe. Lodging houses and small hotels continued to be built throughout the nineteenth century, supplying accommodation to the many thousands of visitors to the county’s coastal resorts, but they operated on a different level, and offered little competition. This was in part a result of scale, in part standards of service. Setting was a further decisive factor. The Grand at Scarborough, the Alexandra at Bridlington Quay, the Zetland at Saltburn and the Metropole at Whitby could all provide meticulous service in superior locations.

All signalled this difference by their architectural presence, many on clifftop sites and taking advantage of the best views. In this sense they also implied a social hierarchy in which their guests occupied the topmost tier.

Article taken from ‘The Golden Age of Yorkshire Resorts’ by George Sheeran, published by Amberley Publishing, £15.99 paperback

Author George Sheeran will be taking part in a talk and book signing session at the Sitwell Library in Woodend on 1st July 2023 from 11:00am-1:00pm