Dr Korczak’s Example – Review – Leeds Playhouse

By Eve Luddington, January 2020

‘This story happened. It happened.’ So begins Dr Korczak’s Example by David Greig. Commissioned by James Brining for the young people’s theatre he directed in Glasgow, its first performance was in 2001. This new production, also directed by Brining, is Leeds Playhouse’s contribution to Holocaust Memorial events in 2020. Writing, direction and acting combine to make 80 minutes of exceptionally powerful theatre. At times I could scarcely blink in case I missed something.

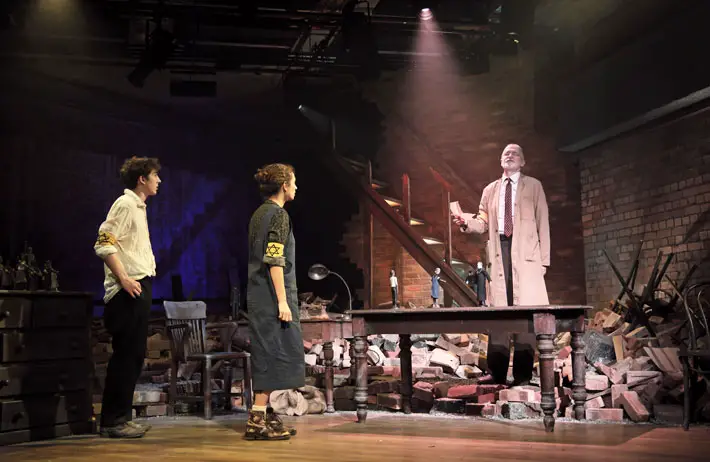

Originally written for young people, the play works just as well for adults because its author David Greig, like his title character, believes in treating children as equals. It uses three actors to tell an important story about an orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942, and explores questions which remain challenging and pertinent today.

The Warsaw Ghetto, built by the Nazis in 1940, comprised 2.4% of the city’s land and contained all the Jews of Warsaw (about 30% of the city’s entire pre-war population), plus some from surrounding districts – up to 490,000 people. Food was scarce and living conditions squalid. Those who tried to escape were shot. In the ghetto was an orphanage run by Dr. Korzcak, a Polish educator, broadcaster and writer who championed children’s rights, believing that children know for themselves what is best for them.

“Illuminate the truth”

Greig’s writing is tightly structured and inherently theatrical. His use of direct address and story-telling enables us to understand his technique of using fiction to illuminate the truth: we’re told at the start that, while Dr Korczak was a real person, the two other main characters, orphans Stepanie and Adzio, are invented. At times they’re represented by small figurines (or, in Adzio’s case and to good effect, a rag doll), as are more characters including other orphans.

The style ensures that we are at a remove from the grim action and so able to consider the ideas of the play, but Greig’s skilled handling of his characters, fortified by scrupulous direction and compelling acting, makes us engage with them and their world, too.

When the play starts, Dr Korczak has spent two years establishing a progressive community with the 200 abandoned or bereaved young people in his care. He has given the children the rights and responsibilities to make rules and to judge their peers in their own court. And he sets the example of finding goodness in everyone by his own behaviour. The orphanage has become a safe haven where children are treated seriously and with respect, and Dr Korczak has been assured by the authorities that it will remain so.

Into this refuge comes Adzio, a boy who’s survived by living in the sewers and stealing food. According to the rumours he’s heard, the orphans will soon be transported. What’s the point of civilised behaviour when it will lead, he believes, to passive acceptance of a cruel fate? He brands the doctor a ‘mad old monkey’.

“Completely believable”

But Adzio is not immune to human feeling and, before long, he’s drawn into a relationship with Stepanie, another orphan and Dr. Korczak’s trusted assistant. Like Stepanie, the audience weighs Adzio’s fighting instincts against Dr. Korczak peaceful resistance to the Nazis. And when Stepanie is forced to choose between the boy’s ways and the man’s to have any chance of survival, we are considering what we might have done in the situation. It’s very powerful stuff.

James Brining’s insightful direction exudes commitment to the piece and understanding of what the audience needs to engage with it. A soundscape of children’s voices burbles in the background, never dominant but insistently present. Small symbolic details are hugely resonant. When Adzio first arrives at the orphanage, he is weighed. The rag doll that sometimes represents him is put on a scoop on food scales: it weighs less than a potato and a couple of small carrots. Later, the same scoop is used to depict the first bed Adzio has slept in for years.

All three actors, performing a few metres from the audience, inhabit their main roles fully and take on one or two minor ones too. Individually and in their interaction, they are completely believable.

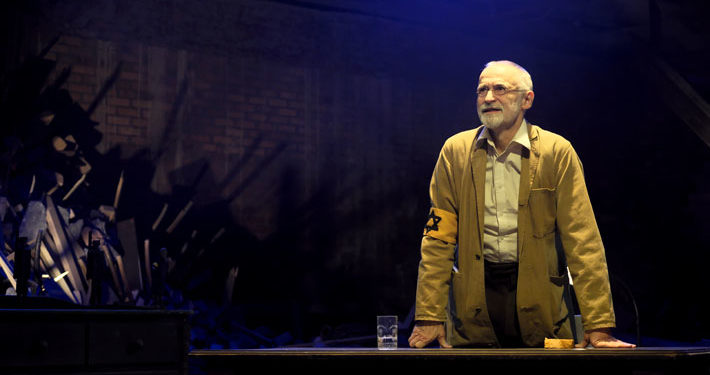

As Dr Korczak, Rob Pickavance (Scrooge in Leeds Playhouse’s A Christmas Carol) is an unassuming and dignified presence. He embodies the doctor’s legendary kindness and unwavering devotion to those in his care, making it easy to understand how such a man could gain the trust of terribly damaged children. Pickavance conveys with equal sensitivity Korczak’s internal monologues to an imaginary Nazi soldier. These trace the doctor’s thought patterns and private torment as it gradually dawns on him that his lifelong belief in people’s goodness is completely undermined by the Nazis’ behaviour: they have lost any semblance of humanity.

“Powerful rapport”

Gemma Barnett plays Stepanie. Her face reflects every fleeting thought of the girl who has to make tortuous choice between her ‘saintly’ doctor and his teachings, and Kadzio, with his drastically different answers to questions of life and death. She and Danny Sykes as Kadzio have a powerful rapport and relate convincingly as wary strangers, tentative friends and ultimately, as desperate lovers.

I had to read twice the Google entry that told me Adzio is Danny Sykes’s first professional theatre role. He is incredible. A feral scavenger, we sense that his agility is driven by hunger. Aggressive in speech, he’s always at the very tipping edge of fight or flight. But in his eyes we see the fear at the core of him: this young boy has lived a wretched life and has no reason to trust anyone at all. Sykes drew me in so completely as Kadzio that I felt at times as if I were him. And yet he also impersonated the leader of the ghetto, an entirely different character, credibly. My only quibble about Sykes’ performance concerns not his acting, but one word the script requires Kadzio to repeat time and again as he dreams of his ideal breakfast: ham. Would a Jewish lad like him ever dream of ham? It’s a tiny detail to criticise but, for a few moments, this odd choice of non-Kosher food distracted my companion and me from the action.

My only major reservation about this production is in the choice of set. The design itself is impressive: an oasis of relative order – table, chest of drawers, hat-stand and chair – surrounded by a mountain of destruction. Poking out from the rubble, there’s a teddy bear, a bunch or two of flowers. It’s visually stunning but it’s a bombsite, not a ghetto. It didn’t help me to feel the overcrowding of the ghetto or the cruel irony that the buildings in it remained intact while the captive residents were slowly destroyed.

“Grain of hope”

Otherwise all the production elements merge to tell a grim story compellingly, with great respect for the real and imagined protagonists. That respect is extended to the audience; there’s no appeal to cheap sentimentality and no gratuitous violence in this production. Contained within the play is a grain of hope that, one day, Dr Korczak’s humanity, dignity and beliefs would bear lasting fruit.

On our way out of the auditorium, each of us is handed a postcard. One side bears a quote from Dr Korczak under the heading, ‘Children are not the people of tomorrow, but are people of today’. On the other side, 17 ‘Rights of the Child’, written by Korczak, are listed. Most of those were included in the UNESCO Charter for Children’s Rights after the war.

The last survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto died in 2009. But Axel Hersh MBE, who was a child in Poland’s other main ghetto in Lodz and later survived several death camps, lives in the Leeds area. A drama based on his and other child refugees’ experiences immediately after the war, The Windermere Children, is available on BBC i-player as is the documentary, ‘The Windermere Children: In their Own Words’. Hersh will be contributing a post show-discussion of Dr Korczak’s Example on 11th February. I, for one, hope to be there too.

images: Zoe Martin