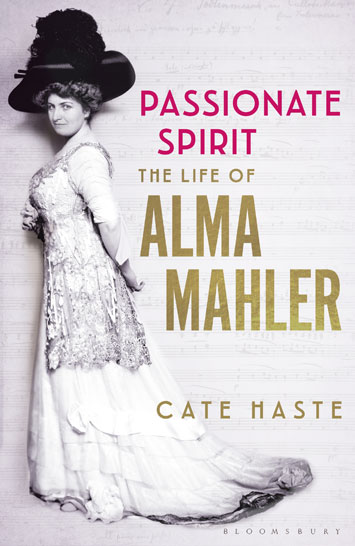

Passionate Spirit: The Life of Alma Mahler by Cate Haste – Review

By Jeff Halden

Her daughter Anna summed up Alma Mahler thus: ‘She was a big animal. And sometimes she was magnificent and sometimes she was abominable’. Cate Haste’s comprehensive biography offers an illuminating portrait of this larger than life women, which attempts to redefine her as a remarkable, talented individual in her own right.

Alma Mahler has tended to be identified with the men in her life, and the author describes in some detail her marriages; to the composer Gustav Mahler, the architect Walter Gropius and author Franz Werfel and her affairs; with the painters Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka and others too numerous to list here. However, the author’s central premise is that Alma had a passion and talent for music which she sacrificed in order to act as a muse to these men. This is a persuasive argument, which Cate Haste largely succeeds in substantiating in this well-written study.

The book draws extensively on Alma’s unpublished diaries and letters and are quoted at some length throughout the book. Whilst undoubtedly giving us an unrivalled insight into Alma’s private thoughts, they do tend to interrupt the narrative flow at times. In this, at times, too sympathetic portrait however, Haste makes it abundantly clear that she was a gifted composer with a life that was overshadowed by tragedy, with the premature death of her first husband and three of her four children.

Born in 1879 in Vienna, the centre of the Hapsburg Empire’s artistic and cultural life, Alma died in New York aged 86, a remarkably long life given its various trials and tribulations (often self-inflicted). Cate Haste is particularly good at setting her life against the great European political, cultural and social events of her time. Potential readers should beware that this is Alma’s life from her own point of view – given the wide-ranging use of her diaries and letters. This reviewer would have liked a more critical appraisal by the author, particularly of Mahler’s crude anti-Semitic views.

“Tempestuous relationship”

The biography is traditional in format, describing her upbringing in the Bohemian circles in which her parents Emil and Anna Schindler moved. Following Emil’s early death, Anna’s second marriage to the painter Carl Moll led to a strained relationship with Anna which overshadowed her teenage years and early adulthood. Alma’s overwhelming passion was music, especially opera, and her first serious love affair was with the painter Gustav Klimt, a three year whirlwind of emotions which was seemingly never consummated. Over by 1900, there followed a volatile and tempestuous relationship with the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky which again, despite breathless diary entries, never seemingly carried to a conclusion.

The biography is traditional in format, describing her upbringing in the Bohemian circles in which her parents Emil and Anna Schindler moved. Following Emil’s early death, Anna’s second marriage to the painter Carl Moll led to a strained relationship with Anna which overshadowed her teenage years and early adulthood. Alma’s overwhelming passion was music, especially opera, and her first serious love affair was with the painter Gustav Klimt, a three year whirlwind of emotions which was seemingly never consummated. Over by 1900, there followed a volatile and tempestuous relationship with the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky which again, despite breathless diary entries, never seemingly carried to a conclusion.

It was in October 1901, with Gustav Mahler’s appearance on the scene, that Alma’s life changed forever. Already a notorious womaniser, and described as ‘an elderly degenerate’, Mahler was 41 and Alma 22 when they began their affair. Henceforth, she abandoned herself and her own creativity for what she believed to be a higher cause, that of the creative genius of the men in her life. Alma and Gustav were married in March 1902; tragically in 1907, the Mahler’s eldest child Maria died from diphtheria and scarlet fever and Gustav himself died of a heart condition in May 1911. Alma, by then, had already met and fallen for the modernist architect Walter Gropius. By this time she was 32 and, as the photographs in the book make clear, was a statuesque beauty. In April 1912, she met Oskar Kokoschka – described by Gustav Klimt as ‘the greatest talent of the younger generation of painters’ – and began a tempestuous relationship that continued on and off for the rest of her life.

Despite this she married Gropius in August 1915, a daughter being born in October 1916. Described by her as a ‘stocky, bow-legged somewhat fat Jew’, it was in November 1917 that she met and fell for Franz Werfel, a poet and novelist. October 1920 saw Alma and Gropius divorced, and it was not until July 1929 that Alma and Werfel were finally married in July 1929 in Vienna City Hall.

In August 1929, Alma was 50 and not physically well. However, established in her opulent new mansion, she entertained the elite of Viennese society and culture.

“Provoke very mixed and powerful reactions”

Werfel, meanwhile, had become one of the most widely-read authors in the German language, but that did not prevent his books being burnt along with 25,000 others by Jewish, religious, socialist or communist writers by Nazi stormtroopers throughout Germany in May 1934. Tragedy continued to haunt Alma when, in May 1935, her and Gropius’s daughter Manon died of polio.

In March 1938, the Wehrmacht marched into Austria and this prompted Alma and Werfel to leave Vienna in order to escape Nazi persecution.

Cate Haste’s description of their epic wanderings and surmounting of obstacles, both physical and bureaucratic, over the next two years, before finally ending up in New York in October 1940 is gripping and for me, one of the highlights of the book.

In December 1940 they moved to Los Angeles and stayed there until September 1947 when Alma returned to Vienna, alone, to try and recover lost manuscripts, letters and paintings left behind when she fled Vienna before the war.

Following Franz Werfel’s death in 1945, Alma re-established herself in New York for the remaining years of her life, attending concerts and cultural events and going to the opera. ‘Great men continued to cross my path’, she characteristically confided to her diary.

Outside her own, select circle, Alma could provoke very mixed and powerful reactions: ‘…painted, powdered, perfumed and inebriated. This bloated Valkyrie drank like a fish.’

However, Cate Haste, in this fascinating and comprehensive study, sums her up thus: ‘Although she was famous for her attraction to creative geniuses, throughout her life it was not the men who were her saviours. Composing, playing or experiencing music in different forms was her crystalline core.’

The book is admirably well-researched as the bibliography and fifty pages of notes underline and largely convinces in its aim of re-assessing Alma Mahler’s influence on European cultural life during the twentieth century.

‘Passionate Spirit: The Life of Alma Mahler’ by Cate Haste is published by Bloomsbury, £26 hardback