Ripley Ville, Bradford – The Industrial Model Village

By Paul Chrystal

The industrial model village grew out of the lamentable conditions in which workers were obliged to toil and live during the Industrial Revolution. The villages were a culmination, generally speaking, of a growing awareness that something had to be done about the overcrowding and the insanitary, disease-ridden houses and squalid streets that droves of workers left each dawn for the inhumane factory conditions and relentless labour that paid their meagre wages.

The industrial village concept, however, was never just a question of altruism, philanthropy or paternalism. The welfare could never exist without the business, and profitable business at that: the difference between the industrialist who built his model village and the average factory owner was that the benefactor felt the need to reinvest his profits for the betterment of his workers while at the same time benefiting from a stable, more productive, comparatively happy workforce.

The serious shortcomings of back-to-back housing – the predominant form of working-class housing for many years – were there for all to see in all industrial towns and cities, and most of the agencies involved agreed that something radical had to be done to stop the proliferation of what were little more than wretched hovels.

“Mount a campaign”

A bylaw of 1860 theoretically banned construction of back-to-back houses, but, predictably, the building companies rallied together to mount a campaign to rescind the bylaw, their argument being that it was not possible to build ‘through’ houses at a price that working-class people could afford.

Politics intervened when in the local elections of 1865 the chairman of the Building and Improvement Committee lost his seat and was replaced by a councillor sympathetic to the builders. In 1866 Bradford Council caved in and revised the bylaw to permit construction of back-to-backs ‘provided they met stringent requirements for space, ventilation, water supply and sanitary provision’.

These ‘tunnel backs’, as they became known, became Bradford’s major form of working-class housing during the next twenty years. Profit was obviously the determining factor. No back-to-backs were approved after the 1870 bylaw but the builders had enough approvals in hand to allow them to go on building them into the 1890s. Ripley was far from convinced and questioned the motives of the construction companies.

“Productive workforce”

In November 1865, frustrated by the vested interests of builders in relation to construction of affordable housing and the dithering of the council, Ripley issued a prospectus for the construction of 300 ‘Working-men’s dwellings’ on his own land: four-bedroom through houses with rear yards and front gardens and an internal WC. These houses were to be sold to small landlords and owner-occupiers. Lighting, ventilation, heating, storage, privacy and open space were taken into consideration and the design of the Ripley Ville houses incorporated these enhanced standards, and in a number of ways exceeded them.

By the time Ripley Ville was established there was a long tradition of industry-based model villages in England, all with their own variations. They included Robert Owen’s and David Dale’s 1786 New Lanark; Swindon Railway Village (1840s); Titus Salt’s Saltaire (1853); Edward Akroyd’s Akroydon, near Halifax (1859); Nenthead, Cumberland (1861); and New Sharlston Colliery Village, near Wakefield (1864).

Ripley was followed by, among many others all with significant variations, Cadbury’s Bournville; James Reckitt’s Quaker garden village in Hull in 1908; Joseph Rowntree’s New Earswick, near York (1902); and Lever’s Port Sunlight. One thing that the visionary and enlightened industrialists behind these settlements had in common was the firm belief that a contented, comfortable and well-nourished workforce was a productive workforce.

“Bounded by railway lines”

Living in overcrowded, insanitary and damp slums with family life lubricated with drink and punctuated with domestic violence and regular visits to the pawnbroker was not conducive to achieving targets or meeting orders. While profit margins were never compromised – they always came first – Henry Ripley, Cadbury, Rowntree and others all saw that margins were more achievable, market share was more winnable and competition was more beatable if the men and women on the shop floor or on the road were in a fit state to put in a productive day’s work.

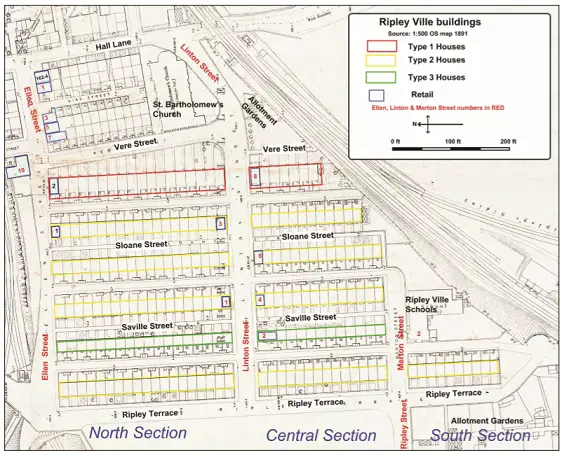

On 24 January 1866 planning permission to build 254 houses was granted. Invitations to tender went out for 200 houses plus one school, approval for which was given 8 June 1867. All the houses were built by early 1868. Thirteen terraces of houses along four residential streets were laid out on a north–south axis. Early builds were completed with inside toilets in the cellar – later retro-fitted with external ash closets – while later versions had outside external ash closets from the start. WCs were the preserve of the middle classes, virtually unknown in working-class houses – except for those originally planned in Ripley Ville.

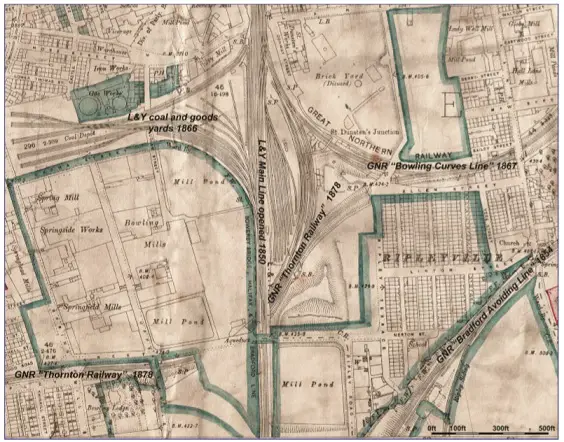

By 1871 the site was bounded by railway lines on three sides, on a triangle of land between east and west Bowling and to the north of Bowling Dye Works. (Bowling) Hall Lane lay to the east. In December 1868 the Bradford Ten Churches Building Committee agreed to build a church in Ripley Ville on land donated by Ripley – St Bartholomew’s Church was consecrated in December 1872.

“Coal store”

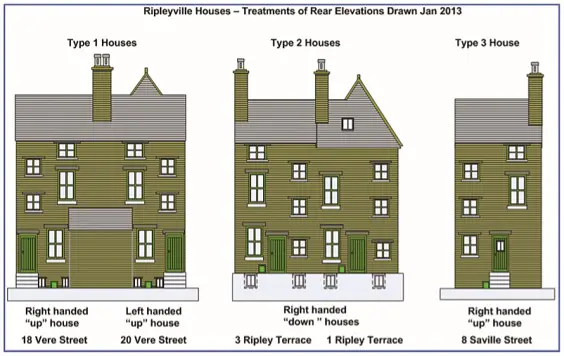

Ten almshouses were built by Ripley in 1881. So rose Ripley Ville, a townscape which remained intact for 100 or so years. The development featured 196 houses with three sizes. Type 1 houses had two large groundfloor rooms and a scullery in a back extension. The cellar was fitted out as a ‘cellar kitchen’ with a sink and range. The cellar also contained a WC and a coal store.

Type 2 houses boasted a large front ground-floor room and a smaller back room. The basement contained a storage cellar, WC in houses built under tenders 1 and 2 and coal store.

Type 3 houses had a single ‘through room’ and small scullery on the ground floor. The basement contained a storage cellar, a coal store and a second enclosure. No WCs were fitted to Type 3 houses.

“Converted”

All lived-in rooms had gas lighting and a fireplace or range. Fireplaces in the bedrooms were decorative cast iron. As in many other model villages, selling alcohol was prohibited although the 1872 Smith’s Directory lists Stephen Gibson of No. 2 Linton Street as a grocer, tea dealer and beer retailer.

There was no pub, but residents could drink at the nearby Locomotive Inn (which existed before Ripley Ville) at No. 7 Ellen Street, or in Hall Lane at the Bowling Hotel.Four other beer retailers are recorded in Smith’s Directory. An inn called the Gibson Arms on Linton Street and part of the village seems to have been converted from two properties at some point.

Employment by Ripley was never a qualification for Ripley Ville residency. When (from 1881) Sir Henry Ripley died in 1882, his younger son, also Henry, took over as manager of the dye works. Ownership and control of the dye works passed, in 1899, to the Bradford Dyers Association, marking the end of the Ripley family association with the works or with Ripley Ville.

Taken from ‘Bradford at Work’ by Paul Chrystal, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99

Taken from ‘Bradford at Work’ by Paul Chrystal, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99