The Story of Titus Salt and Saltaire

Salts Mill in Saltaire, Bradford is an iconic Yorkshire building. Built by businessman and philanthropist Sir Titus Salt it has a long and fascinating history. In a new book, Maggie Smith and Colin Coates profile the owners of the mill, from Titus Salt himself, to the modern day. In this excerpt, the writers examine how Salt came to build the mill and its associated village of Saltaire – and how he came to be remembered as one of Yorkshire’s greatest – and most compassionate – businessmen…

To gain an insight into the man who built Salts Mill and founded Saltaire, it is important to understand how he came to be involved in textile manufacture and what influences would have shaped his personal and business life.

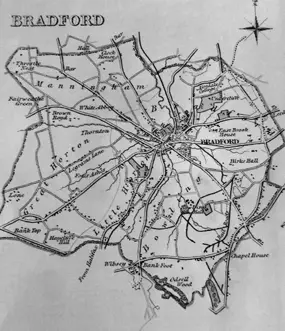

The most authoritative work on Titus Salt, The Great Paternalist; Titus Salt and the Growth of Nineteenth-Century Bradford (J. Reynolds, 1983) provides a thoroughly researched work exploring the social, political and economic changes of Salt’s time. Reynolds takes the starting point for his work as 1847, noting that the populated areas of what was to eventually become the City of Bradford involved four townships: Bowling, Heaton, Manningham and Bradford itself.

Its economy then was based on a mixture of farming and manufacture, due to an important change in the late seventeenth century when worsted stuff manufacture was introduced to the west of the West Riding from East Anglia. Worsted cloth was different to woollen cloth, using different types of yarn. The long wool fibres were spun together along the axis of the yarn, creating a smoother cloth that enabled pattern definition. The separation of long fibres (tops) was achieved by combing the wool with heated, heavy metallic combs, leaving short fibres (noils) that were sold to wool manufacturers.

“Spinning processes”

Wool combing and weaving were almost entirely domestic industries that were well established by the mid-nineteenth century in the area of the townships and, while there were several factories in the parish of Bradford, there were none in the town itself at this time. The first significant change in the parish of Bradford had occurred in the eighteenth century with the establishment of iron manufacture in Bowling and Low Moor. There were plentiful coal deposits in these areas, providing tools and fuel for the emerging textile industry. By 1780, the local population involved in worsted manufacture had risen from 25 per cent to between 45 per cent and 50 per cent. At the turn of the century, the bulk of the spinning processes were carried out in factories that employed women and children to do the work.

The power loom was introduced in 1824 and experiments with machine wool combs had begun. The wool market itself moved from Wakefield to Bradford and leadership of the Bradford textile industry was firmly in the hands of manufacturers and merchants. Reynolds (1983) notes:

“There were few restraints on entrepreneurs, few social demands on profit, low rates for the parish, public space available at low cost, no regulations on hours of work and the capital cost of expansion was very low.”

“A new working class”

Thus by the 1830s Bradford had become a magnet for people seeking work or business opportunities, experiencing a further population growth of 78 per cent in the first third of the nineteenth century. There was a well-established upper class of conservative, Anglican gentlemen, but a new middle class had begun to emerge among well-to-do farmers, important manufacturers, and merchants. The economic interests of both groups were similar, but religious affiliations differed, as did political affiliations. The new middle class were often ‘dissenters’ in terms of religion and liberal in their political views.

This exponential population growth and continuously increasing mechanisation of worsted manufacture had a number of social and moral impacts that were of concern to both the upper and middle classes. The townships moved rapidly from relatively small communities where people living in the areas had strong familial roots and communal networks. In itself, this meant that individuals and families were known by and knew many others living and/or working nearby. This provided some degree of ‘social control’, in that any wrong-doing would be noticed and subject to communal censure. The advent of a population of strangers – both to the indigenous population and to each other – appeared to create a ‘licence’ for immoral and unwelcome behaviours that were much more difficult to counteract with community pressures.

In addition, some of the ‘masters’ in the textile crafts, who had ‘put work out’ to home-based workers, gradually lost their prior status and resented this. In fact, the changes to the area created a new ‘working class’ who had very hard times when work was short. This in itself brought active involvement for some working people, in the formation of trade unions and allegiances to the radical Chartist movement.

“Sympathy with ‘moral force Chartism’”

Chartism was a national working-class movement, which emerged in 1836 and was most active between 1838 and 1848. The aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights and influence for the working classes. Chartism got its name from the formal petition, or ‘People’s Charter’, that listed the six main aims of the movement:

– All men to have the vote

– Voting to take place by secret ballot

– Parliamentary elections to be held every year, not every five years

– Constituencies to be of equal size

– Members of Parliament to be paid

– The property qualification for becoming a Member of Parliament to be abolished

The origins of Chartism were complex and, for William Lovett, peaceful persuasion by respectable working men – ‘moral force’ – was the best way to win the points in ‘the Charter’. This strategy clashed with that of Feargus O’Connor, a charismatic speaker who used mass meetings and the widely read Northern Star to unite the forces of the working class behind him. His popularity was immense and he advocated the use of physical force to fight for the charter. Chartism was a national movement, but it was particularly strong in the textile towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire, as well as other areas where rapid industrialisation created large working-class populations.

The movement was formed not very long after the French Revolution, which had similarities in uniting the poor and the middle classes. Its existence was certainly of concern to the property-owning men of both conservative Anglican or Liberal/Radical background. The difference between the two classes, however, was important and many among the emerging middle classes had sympathy with ‘moral force Chartism’.

“Ardently supported political reform”

It was at the beginning of this transformational period that the Salt family arrived in Bradford. Daniel Salt brought his family to the town probably in 1820 or 1821, when he was aged thirty-eight or thirty-nine years. He had considerable experience of business and had been an iron founder, a dry salter and a white cloth merchant; he also begun farming in 1811. He’d been attracted by Bradford’s expanding economy and sold his farm to invest the capital in the wool industry. Salt took an office in the centre of Bradford and established a wool-stapling business – buying wool from suppliers, sorting and grading this and then selling it on for spinning and weaving. He also bought land in Cheapside and built first one and then a second warehouse in Bradford that became his headquarters.

He was a West Riding man with useful connections, and was well established in the dissenting community; a Congregationalist in faith. He rapidly immersed himself in public life in Bradford. In 1824 he was appointed to the vestry office as an overseer of the poor; in 1825 he was named as a commissioner. Then in 1831 he was elected as a constable of the manor and ardently supported political reform for the emancipation of Catholics, the abolition of slavery and demand for ‘Free Trade’. In 1837 he was elected to the first Board of Guardians and from 1835 to 1841 was prominent in radical organisations.

He was a tall, well-made man with a reputation for intelligence and wit and, despite his faith, was not known to be a rigid puritan. He had a well-pronounced stammer that did not seem to affect his progress in either business or public life.

He had eight children with his wife Grace Smithies; Hannah Marie (b. 1806) and Hannah (b. 1821) died in infancy, while Isaac Smithies (b. 1810) died at the age of nine years. Five children survived, and Daniel had built the family a home in Manningham by 1834. His wife Grace was known to be devoutly religious, and she gave all the Salt children their religious education. The oldest son Titus was nineteen years of age when the family arrived in Bradford; sisters Sarah, Ann and Grace were eighteen, four and ten years of age and brother Edward was eight years old.

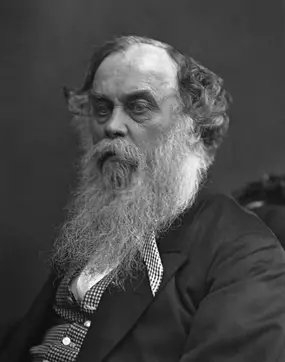

Titus, born in 1803, was initially educated in a ‘dame school’ in Morley (near Leeds), and then at Batley Grammar School. He was later given a plain commercial education at a Wakefield school run by a Mr Enoch Harrison. Salt was described as tall and stout, with a heavy appearance, and as having a studious turn of mind, rarely mixing with his school fellows and being somewhat introverted. He was known to have some difficulty in reaching decisions and was unable to speak confidently or coherently in public. He had a highly developed sense of responsibility, however, and this offset his diffidence.

“He was a firmly committed liberal-radical dissenter”

In 1820 Titus had been apprenticed to a wool stapler, a Mr Jackson of Wakefield, and when the family came to Bradford he spent two years with William Rouse & Son, where he gained a more comprehensive insight into the textile business. In 1824 he joined his father, and the firm became Daniel Salt & Son. Titus worked in the family firm for ten years, during which time the firm began to specialise in Donskoi wools from Eastern Europe. He took part in public life alongside his father and was also a firmly committed liberal-radical dissenter. In 1826 he was enrolled as a special constable during rioting at Horsfall’s mill when a very bitter strike took place in the local worsted industry.

This perhaps indicated both his own strong concerns about worker unrest and his concern to sustain the rights of employers. At this time, he was also appointed as superintendent at Horton Lane Chapel Sunday School, although he was too timid to read the prayers to the congregation.

In 1830 he married Caroline Whitlam of Grimsby, the youngest daughter of Mr George Whitlam, who was a wealthy sheep farmer. He first took a house in North Parade, Bradford, very near to his parents’ house but, between 1836 and 1843, he lived at the junction of Thornton Road and Little Horton Lane. This was very near Nelson Court and Fawcett Court, the heart of the worst slum property in Bradford, and his understanding of the deprivation of many families will have developed here. His eldest children spent their early years living very close to this part of town. William Henry was born in 1831; George in 1833; Amelia, 1835; Edward, 1837; Herbert, 1840; Fanny, 1841; and Titus, 1843.

Salt and his father had started a spinning department of their wool-stapling business, using rooms in Thompson’s Mill at Goitside Thornton Road, Bradford. They had been joined in the business by Edward Salt in 1834 and, shortly after this, Daniel Salt retired. Within a few months Titus had also left the firm and started to work on his own account (the family partnership was dissolved in 1835).

Titus Salt started his new venture at Hollings Mill and quickly acquired premises on or near Hope Street. In 1836 he took over a large mill in Union Street (whose previous owner had been Daniel Illingworth) and this became the headquarters of his rapidly expanding alpaca manufacturing. He also employed large numbers of hand woolcombers in the Manchester Road area and hand weavers in the nearby villages of Allerton, Clayton and Baildon. His success was aided by newly acquired capital from his father’s will, and he was to add three more Bradford mills to his business before the mid-1840s.

“Member of the inner circle”

The wealth from his business supported his very active public career and, at one time or another, he occupied almost every local public office. He was elected High Constable of the Manor in 1841/42, organising and presiding at all town meetings requisitioned by the required number of rate payers. From 1847 to 1854, he was the senior alderman in the new Bradford Corporation for South Ward. In 1848/49 he was elected mayor of the town and presided at almost all full council meetings. He also sat regularly on the bench of the Bradford Court and was an active member of the Chamber of Commerce. He was always a member of the inner circle of well-to-do radical dissenters who played a leading role in the reformation of Bradford’s public life.

Meanwhile, through the forties and fifties he was particularly active in politics, supporting the cause of the Anti-Corn Law League and showing much sympathy with the ideals of ‘moral force’ Chartism. While demonstrating a view that working people should be loyal to their employers, he clearly sympathised with the plight of the growing urban working class in that they had somewhat precarious incomes with which to care for themselves and their families, while having little access to decent homes.

Although it had become a dominant area in the wool trade, Bradford had been slow to develop any innovations in textile manufacture during the period in which the Salt family lived there. Success had come about through the adaptation of devices and inventions in machinery. After 1836 the production of mixed rather than pure woollen fabrics had commenced, wherein cotton and silk were used with wool and mohair – innovation driven by difficulties in obtaining sufficient quantities of long-fibre wools. At the same time the manufacturers created a demand for lighter and more elegant fabrics. Use of a wider range of materials also cheapened the costs of production. By 1837 Bradford mills were using cotton as warps, but what was to become more important was the development of cloth that utilised the long, shiny hair of the alpaca.

“Only spinner of alpaca weft in Bradford”

Alpaca, imported from Peru, became known in the United Kingdom in the early years of the nineteenth century, when new trading connections were being developed with Latin America. Although several amateur innovators experimented with the new material, it was not until the 1830s that its commercial properties were tested. Early trials in worsted manufacture with this material were problematic. The first attempts to produce cloth with it, carried out by Benjamin Outram of Halifax, involved very high costs and the finished cloth lacked lustre. A number of other firms also produced experimental materials but were not able to capitalise on its potential by discovering how best to comb and spin this new material.

Titus Salt, however, was no stranger to experimentation and had followed his father’s lead in the use of Donskoi wool. He had the persistence and ingenuity to resolve the problems with alpaca wool. Salt was experimenting with alpaca wool by 1837 and there is documentary evidence in his small day book, kept between 1834 and 1837, wherein he recorded costs of the material and its processing. It was to be trials with alpaca weft and cotton warp that proved successful, and there are records of his early sales of the new cloth in 1839. Titus Salt was the only spinner of alpaca weft in Bradford.

He had worked in great secrecy for eighteen months with trusted assistants, and the cloth he produced in this way was durable, relatively light, lustrous and reasonably priced. Salt and others also made greater and greater use of mohair from the Levant and small amounts of Australian wool.

“Reached the highest level of wealth”

By 1843 he had had enormous success and had ceased to live in Bradford, moving with his family to a handsome mansion called Crow Nest at Lightcliffe (near Halifax), 10 miles away from his business and his public commitments. By this point in time there were a number of Bradford textile manufacturers who, by any standards, were wealthy men. Some joined the ranks of the aristocracy and titled gentry, and a number confirmed their success in industry by converting their resources into landed estates. Samuel Cunliffe Lister bought the Masham and Jervaulx estates in North Yorkshire and, some years later, became Lord Masham. Among the non-titled, Mathew Thompson bought an estate in Kent; John Wood had many acres in Hampshire; and George Hodgson, the textile engineer, bought an estate in Norfolk.

In 1851, Henry Forbes estimated the value of the British textile trade at £12,500,000, of which the West Riding of Yorkshire accounted for £8,000,000. Despite this and the undoubted wealth of many of the Bradford manufacturers, few of the fortunes reached the highest level of wealth. Only one manufacturer of the time was listed as a millionaire at his death – William Foster of Black Dyke Mills.

Titus Salt, one of the wealthy of Bradford, did not choose to convert his fortune into a landed estate (that was to be the choice of his oldest son, William Henry, probably in 1865). Instead he had the originality of mind to go on to build his memorial to the future through the creation of an industrial community settlement, to be named Saltaire. The question as to why he should choose to do

this and act differently to his peers has never been satisfactorily answered. The site he chose for his new mill was four miles away from Bradford in a rural area on the banks of the River Aire at Shipley.

Reynolds (1983) poses some probable practical reasons for siting his new mill there:

- The recent developments in woolcombing machinery allowed him to think in terms of total factory production rather than different mills and machinery performing different functions.

- To buy any quantity of new machinery required him to have a great deal more space than he then had across his six mills.

- To concentrate all his activities in one large mill would cut out waste and enhance supervision of related functions.

- It was impossible to find a suitably large site in Bradford and the site he selected was, on commercial grounds alone, one of the best that could be found in the north of England.

- The site stood between the River Aire and the Midland Railway line, and through its centre ran the Leeds/Liverpool canal. It was a site at the crossroads of the principal lines of communication, north/south and east/west, ensuring cheap transport for coal, raw materials and finished goods.

“Business acumen”

Known to be relatively indecisive, Salt nevertheless set out to build a grand ‘vertical mill’ – one that could take the raw materials in to the factory, as yet untreated, and have the machinery and capacity to perform the many processes required to complete and finish cloth of high quality. He commissioned the architects Lockwood & Mawson to design the mill, and settled on a fifteenth-century renaissance style. William Fairburn, a great engineer of the day, designed the layout of the interior and constructed the engineering facilities. The building of the mill commenced in 1851 and was completed in 1853. It had a production capacity for 30,000 yards of cloth to be completed every working day and employment at full capacity for 3,000 people.

Salt was aided in equipping his new mill by being one of only two men to get the better of Samuel Cunliffe Lister. Lister, another of Bradford’s major cloth manufacturers, was a skilled inventor himself. He had developed a practice for buying the patents of all new textile machinery, particularly those involving the difficult mechanisation process for woolcombing. Salt collaborated with Edward Ackroyd, the Halifax worsted manufacturer, to buy the Heilman patents, which they both knew Lister needed to gain a monopoly in the manufacture of machine combs. They paid £33,000 for this but defeated Lister, much to his chagrin. As a result, Salt was able to stock the woolcombing shed at Salts Mill at a cost of £200 per machine rather than the £1,200 that was Lister’s market price at the time. Reynolds (1983) recounts this as clear evidence of Titus Salt’s business acumen and dogged determination to succeed.

The new mill had a grand opening on 20 September 1853, Salt’s fiftieth birthday and an occasion of lavish hospitality. The business was to remain a family firm throughout Salt’s lifetime. Salt brought in as junior partners two very able men from his senior staff in 1854: Charles Stead and William Evans Glyde (the brother of Jonathan Glyde, the Horton Lane Congregational pastor). His sons William Henry and George Salt entered the firm at the same time, and Edward Salt joined the firm around the time when Glyde decided to retire, probably in 1865. Titus remained as senior partner all his life, his position very clearly defined by the articles of association for the company.

His vision for his business was much greater than that of building a mill with an immense capacity for textile manufacture. From the outset, the plan was to also build an industrial settlement. Indeed, the first plan for the settlement to be named Saltaire was more sizeable in scope, as recorded in 1854 it:

“provided for a population of 9,000 to 10,000 and sites for a church, baths and washhouses, a Mechanics Institute, hotels, a covered market, schools and alms-houses, an abattoir and dining hall and a music room.”

“Housing compared favourably”

Salt began the arrangements for building the village as soon as the mill was completed and open. In October 1853, tenders were invited for the first fifty-three ‘cottages’ and, by October 1854, fourteen shops were ready for occupation, 163 houses and boarding houses had been completed, and around 1,000 people were in residence. The village was to develop around the Bradford–Keighley road, and house building was started in a series of rigidly defined parallelograms. Three types of accommodation were made available to fit the needs of particular families, either for the space they required or in relation to the family income or status within the village and the factory. Between 1866 and 1869 the first part of the housing programme was completed. The erection of important public buildings had been accomplished on both sides of what had been named Victoria Road.

A number of shops were included in the new streets, and at all levels the housing compared favourably with housing in Bradford. They were supplied with gas directly to each home from the mill, cheaper than that available locally, and initially water was also supplied directly by the mill. Each house had its own lavatory in the yard, and the streets had been laid out and drained before the

houses were built.

Although most of the public buildings were erected during the final stages of development, some general amenities were available from the beginning. A dining room was built opposite the mill to provide cheap meals for workers travelling in to work. Space there was used for a regular programme of speakers and a factory school started life in the dining room also. The Saltaire Literary Society and Institute began in November 1855; a reading room was open every evening; and a debating society was established. In 1863 wash houses and baths were erected, although these did not prove popular with ‘respectable women’, who preferred to take a bath in their own homes. A smaller factory establishment was added in 1868 on the site of an old water mill at the river’s edge (known then and now as ‘new mill’).

The factory school moved to new purpose-built premises further up Victoria Road. In 1868, forty-five almshouses were built at the southern end of Victoria Road and an infirmary and dispensary was opened on the opposite side of the road. In 1869, the year that Titus Salt was created a baronet, the building of an institute to provide further education and a social club commenced. A park was established across the river with land bought by Salt in 1870 and landscaped attractively by a Mr Gay of Bradford. The final houses in Dove Street and Jane Street were completed in 1875 and, by 1871, Saltaire already had a population of 4,390.

“Relinquished much of the day-to-day control”

After 1861, however, Titus Salt lived in semi-retirement, relinquishing much of the day-to-day control of his grand mill and the settlement of Saltaire to his partners. His wife, Grace, had borne eleven children and, after 1843, the family lived firstly at Crow Nest, Lightcliffe, and between 1858 and 1868 at Methley Hall near Leeds. The family moved back to Crow Nest, which the family had left unwillingly in 1858, when Salt was able to buy it in 1868 and returned thankfully to what they had come to regard as their family home. Both Crow Nest and Mill Hill School today. Methley Hall were said to be ‘furnished with all the elegance and luxurious taste wealth can command’. Balgarnie describes Crow Nest in some detail as a:

“mansion of hewn stone consisting of a centre portion with a large wing on each side, connected by a suite of smaller buildings, in the form of a curve… the south side presents a landscape of secluded beauty, in which wood and lake, lawns and terraces, flower gardens and statuary delight the eye.”

From the time the family moved to Crow Nest, they were able to live the life of the wealthy upper class in luxurious surroundings and in contact with all the important people of the day. Titus Salt himself became a ‘crested and carriage gentleman’, but he didn’t succumb entirely to the status he had achieved. Eight of his eleven children had survived. Whitlam and Mary had died in infancy from scarlet fever, and Fanny of tuberculosis at the age of twenty. Just two children were born at Crow Nest – the youngest daughters, Helen and Ada. William Henry and George first went to school at Huddersfield College, established in 1838 for the children of dissenter families who wanted their boys to have some business education and to avoid the lure of the public school. Here there was a particular emphasis on modern languages, writing, commercial education and book-keeping.

Nevertheless, when Edward was ten years old, in 1847 he and his two older brothers went to Mill Hill school in London, which was a public school for the children of wealthy dissenters. The remaining two sons, Herbert and Titus, went to Mill Hill when they were over ten years of age, but all the brothers left the school in 1855 due to a serious outbreak of scarlet fever there, and they did not return. Titus (Titus Junior as he was to become known) had only two years schooling at Mill Hill.

“Reluctance to speak in public”

How the difference in the early lives of the male children affected their adult decisions with regard to carrying on the family business founded by their father is a matter of speculation. None of the sons had any formal education after the age of sixteen years (the girls were educated privately). All the boys worked in the mill, learning the business at first hand, and all, except Herbert, were accepted into partnership. They all experienced very different social and educational contexts to their father. The question as to how much his character and religious and political beliefs influenced them is a difficult one, given that Sir Titus Salt himself leaves few clues to his own personality and style of parenting.

Reynolds (1983) comments frequently about how Salt’s reluctance to speak in public or to produce written materials left little for the historian to study in order to assess his business methods or character fully. There are few details of how he conducted his business in Bradford, but it is fairly clear that the preliminary processes in textile manufacture – wool sorting, and machine and hand washing – were controlled from Union Street, where administrative and financial matters were also dealt with. He is thought to have enjoyed the benefits that the mixed systems of production gave but, like others, he had to face the social and moral problems it presented in the new, highly urbanised society within Bradford.

His attitude to factory reform, wage remuneration and the introduction of machinery was the standard one for men of his class and time. Wages found their own level and mechanisation could not be artificially controlled. He was not in favour of factory legislation limiting hours of work and, throughout the 1840s, he was chairman of the manufacturers’ opposition committee.

Occasionally it was clear that he was prepared to provide entertainment and parties for his employees. In 1847 he celebrated the Liberal electoral victory with a couple of factory parties, one of which was a tea party and dance at the Odd Fellows Hall for 350 women weavers and their escorts. A newspaper report from six years earlier, however, had him bringing to trial two woolcombers suspected of stealing charcoal from him, which on investigation was not found to be the case.

There were other incidents that show Salt as an employer applying the discipline of the trade as all did at the time, and there is no reason to suppose that Salt was anything other than a strong disciplinarian in matters concerning the work of his company. Nevertheless, Salt emerged from the difficult years of transition and immense growth in the trade with his reputation as an employer unsullied. After building the magnificent mill at Saltaire and founding a village for his employees with better housing conditions than could be found anywhere for workers in Bradford, he began to withdraw from public life and duties. By 1853 he was a regular absentee from most of the corporation meetings he could have attended and let it be known in that year that he did not wish to be re-elected as an alderman.

“Grand old man of Bradford liberalism”

He had sat regularly on the bench of the Bradford Court, applying firm justice to recalcitrant textile workers but also offering personal help to men and women who had suffered harrowing misfortune; however, he ceased his role here in 1854. He remained particularly active in politics in the 1850s and was ready to stand for Parliament in 1857. Salt took a seat in 1859 and remained in Parliament for two years. He found parliamentary life something of a burden and in 1861 resigned his seat.

He was beginning to be troubled by gout, which was to plague him for the rest of his life. Salt was much more rarely seen in public and for his last years was to be much more involved with his charitable, philanthropic activities and the completion of Saltaire. He’d become ‘the grand old man’ of Bradford liberalism and still made some political interventions in these later years, including a strong attack on W. E. Forster’s education policies in the election of 1874. It is clear that his business, his family and his foundation of the industrial ‘town’ of Saltaire were always more important to him than politics or the public life.

The questions remain, however, as to why he founded this lasting memorial, which is now a designated World Heritage Site. A number of academics, writers and others have tried to identify his motives for doing so at the age of fifty years, when the project began; this was a time when he had more than enough wealth to retire peacefully from business.

In David James’s 2004 assessment, he comments,

“Salt’s motives in building Saltaire remain obscure. They seem to have been a mixture of sound economics, Christian duty, and a desire to have effective control over his workforce. There were economic reasons for moving out of Bradford, and the village did provide him with an amenable, handpicked workforce. Yet Salt was deeply religious and sincerely believed that, by creating an environment where people could lead healthy, virtuous, godly lives, he was doing God’s work.”

Perhaps Reynolds (1983) gets nearer to the likely answer. He notes that Saltaire was one of several industrial settlements developed by great employers of labour in the mid-nineteenth century, and he disagrees with those historians who describe it as an example of paternalistic philanthropy:

“It was a company village subject to the control of an employer/landlord and it is primarily as an experiment in industrial relations that it ought to be seen and was in fact seen by contemporaries. It was Salt’s personal response to the pressures urging peace and stability between Capital and Labour which emerged in the aftermath of Chartism.”

“Most mills were silent”

Sir Titus Salt died on December 29 1876. The legend of his charity, compassion and business acumen had spread far and wide long before his death, travelling throughout the United Kingdom and far beyond its shores, where his name and the manufactured cloth associated with it was known and appreciated. He was known to Queen Victoria. She had sent alpaca fleeces from Windsor and was delighted with their transformation at Salts Mill into lustrous cloth. He had been presented with the Grand Medal of the Legion of Honour in 1856 for the excellence of his products. He was a great pioneer in a new era for the United Kingdom.

His funeral procession from Crow Nest to his final resting place in the mausoleum at Saltaire’s Congregational Church was to take many hours; most mills were silent and many workers lined the streets to see his funeral carriage passing, the numbers assembling estimated at around 100,000. Would his legacy continue through his sons, who would hold as their inheritance his creation of a grand, vertical, worsted mill and the industrial community of Saltaire?

Courtesy of Amberley Publishing, ISBN, 9781445657530, price £12.99, available from amberley-books.com