An Interview with Ed Clancy

It’s All In Your Head, Ed

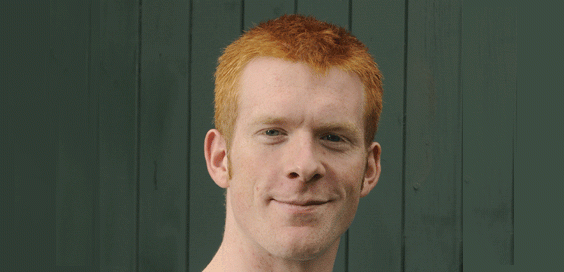

Dave Gilbank takes a revealing glimpse inside the mind of West Yorkshire cyclist and Olympic Gold medalist, Ed Clancy…

When promising British cyclist Ed Clancy was ordered to see a psychiatrist in 2006, the young West Yorkshireman knew the axe was about to fall on his embryonic career.

Big things had been expected of him, and yet he was sputtering along like an old H reg Skoda. The British Cycling powers-that-be had invested much in their young prodigy and were understandably anxious as to discover the reasons why the zigzags on this abundantly talented athlete’s flow-chart weren’t displaying the anticipated upward skew… so what could the problem be?

He was doing the required hundreds of miles in training each week, his diet – carefully monitored and scientifically prescribed – was exactly as it should be, and all the bio-mechanics and computer simulations demonstrated that his technique was just about spot-on. And yet, bizarrely, the ticking hands on the coaches’ stopwatches showed his trial times weren’t getting any faster and, most importantly he wasn’t pushing for a top place in competitive races.

“My first mentor”

“I had my ups and downs,” recalls Clancy. “I was really poor at the Commonwealth Games in 2006 and I didn’t even make the Team Pursuit team. It was really bad form.”

Things weren’t looking rosy for Clancy, and yet this career-low was just the latest in a series of hardships that he had been forced to endure since he was a child.

The boy from Huddersfield had endured a difficult upbringing and if not for the intervention of his step-father, Kevin, things might have turned out differently for young Ed.

“I was hanging around with the wrong crowd on street corners and used to get up to no-good. Things were definitely not looking good for us. Then my mum met Kevin, my step-dad. He was a great role model for me. Kevin showed me that I could have the good things in life by working for them. He was so cool. My first mentor.”

“Results were getting worse”

“Results were getting worse”

Ed left the street gangs behind as he developed a passion for cycling, and was soon rapidly progressing through the ranks of the national junior, then senior squad. Yet by the time of the Commonwealth Games, something was going wrong. Ed had started to doubt his own ability – dangerous ground for any professional athlete.

“I started thinking “is this really what I want to do? My results were getting worse and I couldn’t work out what was going on. It was like there was no reason to live.”

Of course, with statements like these you don’t have to be Sigmund Freud to work out that this likeable young man’s difficulties weren’t physical in nature. So he was soon booked into see the British Cycling Team’s renowned psychiatrist, Steve Peters. This first meeting would prove to be the turning point for Clancy. He began a journey towards identifying the causes that were, unbeknown to him at that time, holding back his progress as both a person and consequently, as an athlete.

“Lack of self-belief”

Clancy is under no illusions about one person in particular whose shadow loomed large over his whole outlook on life. Someone whose actions gave him a fear of rejection and hence a low sense of self-worth.

“My biological father was a problem for me. I didn’t want to end up like my dad. I’d never spoken to anyone about it and I’d kept it bottled up inside me. I’d never thought about it as being rejected or abandoned. But I’d always had it. It left me being afraid to stick my neck out and say what I thought about things. I traced a lot of it back to my father leaving and then not contacting us.”

After his parents’ acrimonious divorce, Ed’s father had suddenly abandoned both he and his brother when they were only very young, and it was only in his sessions with Peters that Ed was able to acknowledge how this event affected his emotional development.

“I guess the whole process with Steve brought me some sense of self-confidence and self-belief. Apparently, divorces affect boys and girls differently. If Girls are brought up by their mums, they get on pretty good. If boys from divorced families are brought up by their mums they grow up with a lack of self-belief. Steve brought this to light for me. He told me I was a lot less self-confident than I thought and that my dad was responsible for a lot of it.”

“I deserve to be there”

“I deserve to be there”

Suddenly, in something like an epiphany, Ed realised just how significantly these demons had been affecting his entire outlook on life.

“I used to wake up in the morning and worry about things. I’d think: ‘I’m never going to beat this guy on the track’. Or ‘such-and-such is riding today, there’s no way I’m ever going to ride with him.’ I just never thought I was good enough or at the same level as them. I imagined that they would push me out of the way and that’ll be it.”

Working with Peters, who Ed describes as the other great mentor in his life (after his step-dad) the troubled young man began to see that he indeed deserved to take his place with the more established names in world cycling.

“Today I think differently. I think “those guys are good and they’re strong.” But I deserve to be there. I’m as good and strong as they are.”

Once he acknowledged how the problems from his past were affecting his adult-life, Clancy was asked to address some fundamental questions. This was so he might take his personal rehabilitation onto another level.

“Routine”

“Steve asked me questions like ‘What do you want in life?’ ‘Where do you want to be?’ We started looking at my whole lifestyle and with his help I saw that all my life was, at that point, an ongoing routine of waking up and training, waking up and training. I wasn’t having any fun.”

Discovering that he could have a rich and fulfilled life, Ed was asked to draw up a list of things that he wanted in his life.

“I put quite a few things on my wish-list. Like winning a gold medal at the Olympics, owning a house, having a girlfriend and a cat. Today I’ve got most of the things on my list except the cat. I’ve got a house and my girlfriend studies medicine in Sheffield. One of things on my list was to learn how to play the guitar. I can almost just about play ‘Stairway to Heaven’.”

History shows that the psychiatric sessions had the desired effect: two years later Clancy would go on to win glory for Great Britain at the Beijing Olympics with a Gold Medal in the Team Pursuit category.

“An amazing feeling”

That’s not all. What makes Clancy’s come-back from the edge of failure so remarkable is that he was instrumental in GB not only slaughtering their beleaguered Danish opponents in the final, but it was Clancy who so brilliantly laid the winning foundation for victory. He produced a now-legendary first lap that set the pace for them to not only win Gold, but also to break the world-record.

“The whole Olympic experience was great. Just walking around the village in Beijing was so weird. Everywhere you went there were all these differently shaped human beings – six foot five volleyball girls in bikinis, massive shot-putters from Africa, American basketballers – it was fantastic.”

The highlight for Clancy was, of course, his team’s victory. He fondly recounts the moment when he knew that his team – also including Bradley Wiggins, Paul Manning, Geraint Thomas (Ed’s best mate) – were going to win the Gold.

“I’ll never forget it. We came round the bend and I could see the Danish team in front of us and that we were almost lapping them. That was when I knew we had won it. It was an amazing feeling. We had won Olympic Gold.”

“We’re number one”

“We’re number one”

As the inevitable accolades and offers have come flooding in, Ed has kept his feet firmly planted on the floor. He is looking forward to London 2012.

“I’ve just started training again and can’t wait to start competing again. We have such great team spirit and camaraderie. We’re number one and aim to stay there.”

As we speak while Ed has his photo taken out on the street near On: Towers, passers-by stop to shake Ed’s hand, offer congratulations and ask to see his gold medal. He obliges without hesitation.

Watching him, it occurs to me, that as sportsmen go, he is unlike most others. While he obviously enjoys the inevitable accolades and adulation that come with being an Olympic Champion – as any young man would – it helps, I think, that he knows where he comes from. That perhaps he has had to work that little bit harder than most of his peers to get to where he is today.

But you won’t hear him say that – after all, he is a West Yorkshire lad.

Pictures: Dave Lindsey