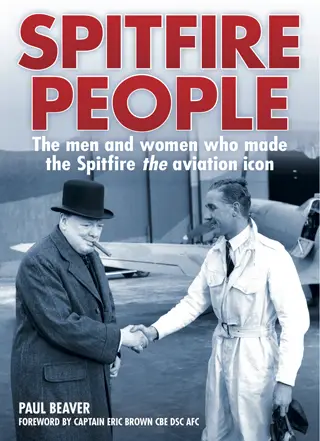

Spitfire People by Paul Beaver – Review

By Rich Barnett

The Supermarine Spitfire, like the Jaguar E-type, has spawned a whole raft of books – so much so it would be possible to fill an entire industrial-sized bookcase with Spitfire-only titles.

Paul Beaver’s Spitfire People takes a slightly different approach, looking, as the title suggests, at the people who were involved in making the Spitfire legend.

Consequently it’s not just the original designer, Reginald Mitchell, and Winston Churchill, who is so linked with the aircraft though his wartime speeches, but a host of designers, engineers, politicians and, of course, the pilots, who propelled the Spitfire into latter-day folklore.

Beaver pulls no punches in his analysis of those he highlights. Neville Chamberlain, the former Mayor of Birmingham, is described as ‘misunderstood’, and while he mis-read tyrants, his ‘contribution to the Spitfire has been overlooked’, Beaver writes. Sir Kingsley Wood, Secretary of State for Air between 1938 and 1940 oversaw an increase in aircraft production, but his Wesleyan background – and consequent efforts – saw him retiring due to mental and physical exhaustion.

“Smitten with flight”

And then there was Noel Pemberton-Billing, born in 1881, smitten with flight and who conjured up the name Supermarine. He was a partner in a steam yacht brokerage based in Southampton along with Hubert Scott-Paine, who went from Supermarine factory manager (1913-1916) to being its owner from 1916-1923.

And Lucy, Lady Houston, who, in 1931, donated £100,000 to the Government to support the RAF’s High Speed Flight and its Schneider Trophy efforts, which lead ultimately to the development of the Spitfire via the S6 seaplane, and the creation of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

Members of the RAF hierarchy are profiled, including Air Marshal Sir Wilfrid Freeman, who was Chief Executive at the Ministry of Air Production from 1942-1945 and Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, who created Fighter Command and saw the value in new technology.

“Captured the public’s imagination”

The flyers rightfully get a look in, whether it was the test pilots taking the earliest incarnations of Spitfires to the sky to iron out any faults, of which there were a few. With the conflict well under way, it was pilots like Group Captain J.E. ‘Johnnie’ Johnson, the leading Spitfire ace, who captured the public’s imagination, along with the likes of Bob Stanford Tuck, Douglas Bader and those from overseas, including the Polish Air Force pilots and ground crew who joined the RAF, and Squadron Leader Mahinder Singh Pujji.

Also rightfully credited are the women, whose contribution is given the attention their effort – both flying and on the shop floor – fully deserved.

In all this is a first-rate read, and should be read by not only Spitfire enthusiasts but those with an interest in the progression and politics of the Second World War. Beaver’s writing is light, well-informed and, where needed, he doesn’t hold back.

Note should also be made of this book’s high-quality: the layout is superb, the choice of photographs equally good, while paper and binding – which can so often let-down books published today – is highly commendable.

Utterly, utterly compelling.

‘Spitfire People’ by Paul Beaver is published by Evro Publishing, £25