The Mystery of the Ripon Sinkholes

By David Winpenny

It’s 19 June 1834 and we’re standing on the edge of a pit, looking down. The shaft is deep – at least 50 feet (15 metres) – and punches its way through the red sandstone to a shadowy, rubble-and-vegetation-strewn base. Yesterday, there was no pit; this chasm opened suddenly. The local newspaper reported that ‘Ripon and the whole neighbourhood was shaken by a tremendous explosion, occasioned by a convulsion of nature, about a mile from the town, by which the earth had been affected to such a degree as to leave a fissure nearly twenty yards in width, and twenty-four in depth.’ While a local diarist noted, probably more accurately, that ‘a large quantity of earth sunk on the hill leading to Hutton, across Sharow Ox Close, leaving a chasm twenty-two yards deep and twelve or fourteen yards wide’.

“Worrying secret”

Two sheep fell into the hole and were, with difficulty, rescued with ropes. Now fenced off on the edge of farmland, the 1834 sinkhole is still visible; trees grow around the top – some of them teeter on the edge of the hole – and the grass grows up to the rim. There are other, similar holes nearby. Forward to 10 November 2016. At around 10.30 p.m., two gardens behind houses in Magdalen’s Road vanished into a sinkhole, which eventually stretched 65 feet (20 metres) wide and was at least 30 feet (9 metres) deep. It disrupted the sewerage system and made neighbouring houses uninhabitable for many months until the hole was filled and the services were restored. In February 2017 another sinkhole appeared beside Ripon Leisure Centre, near the site where a new swimming pool is planned.

Sinkholes are Ripon’s most worrying secret. For millennia they have regularly pockmarked the landscape in which Ripon sits. Areas mostly to the north-east of the city centre – though with others scattered to the west and south – are prone to sudden collapse.

Why is Ripon prone to so many sinkholes? To understand, we need to go back 250 million years to a time when what we now know as Britain was on the shores of a primal ocean, known today as the Zechstein Sea. This was just north of the equator. On this littoral land, where the warm sea lapped the arid sun-baked shore, large mats of algae formed. Over millennia the water evaporated, turning the algal mats into gypsum. You can see remains of the Zechstein seashore, unique in Britain, in the nature reserve of Quarry Moor, to the south of Ripon, just by the Harrogate Road roundabout at the end of the bypass.

“Gypsum collapse”

It’s gypsum that has really shaped Ripon and caused its sinkholes. With continental drift, the land moved north to its current position – and the gypsum came, too. It is mixed with the Permian limestone and marls of this part of North Yorkshire. Unlike most stones, though, gypsum is very vulnerable to being water-soluble. Over the centuries the gypsum pockets dissolve, leaving a series of voids and caverns beneath the surface. Eventually the land above may suddenly collapse into the cavity beneath; into these sudden sinkholes buildings, gardens and agricultural land fall.

If you look at the map of how Ripon has developed, the layout of the built-up area may look illogical; there are large portions where no development has taken place – some of them close to the city centre. These are the places where gypsum lies beneath the surface, though it’s not always possible to be sure where the next sinkhole might appear. When buildings are severely affected by gypsum collapse they are usually cleared away – though a new house that collapsed in 1997 on Ure Bank, just across the River Ure, has been left to crumble back into the land beneath an ever-increasing burden of vegetation. Others, less drastically, are patched up and display the leaning windowsills and doorframes that suggest subsidence.

“Important ancient site”

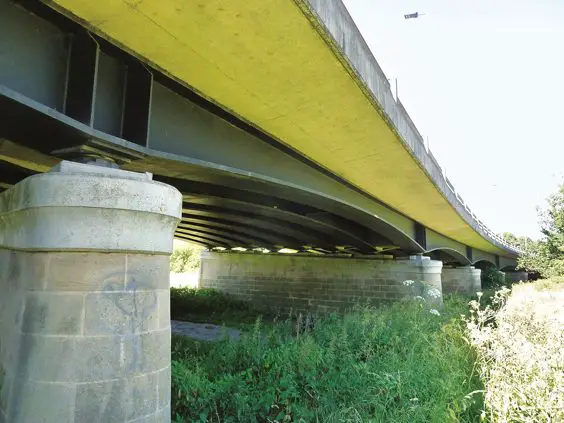

A walk down some Ripon streets – try, for example, Princess Road, eastward from the Clock Tower – will provide examples. The underlying gypsum affected the building of Ripon’s bypass in the 1990s. The Duchess of Kent Bridge, at the bypass’s northern end, takes the carriageway across the River Ure and through the gypsum area. The danger of a sinkhole opening below one of the supporting piers of the bridge was obvious. So the foundations below the piers are extended a considerable distance to each side, and the bridge deck has been strengthened to ensure that even if one of the piers collapses into a subsidence hollow, the deck will remain stable (though no longer useable) and any vehicles will not be precipitated into the river. The piers are also monitored electronically, and the approaches to the bridge are specially strengthened with polymer-based geogrid material.

Gypsum is an enduring problem for Ripon, though it is a versatile mineral, used for plaster and plasterboard, as a fertiliser and in the food and medical industries. As alabaster it can be readily carved, and in medieval monasteries it was mixed with powdered white lead to make gesso, applied to manuscripts before illuminating ornamental letters with colours or gold. Ripon’s gypsum may have provided a source for the monks of nearby Fountains Abbey, for example. Long before the Middle Ages there had been another local use for gypsum. Ripon lies in the lower Ure Valley, one of the most archeologically rich areas of Britain, described by Historic England as ‘the most important ancient site between Stonehenge and the Orkney Islands’.

“Prehistoric landscape”

“Prehistoric landscape”

From Catterick to Boroughbridge a series of henges was constructed in the late Neolithic and Early Bronze ages. The most unusual are the Thornborough Henges, a row of three circular banks and ditches, dating from between 3500 and 2500 BC, whose layout resembles the stars of Orion’s Belt. The central henge was constructed in part over an earlier earthwork, the Thornborough Cursus, a round-ended ceremonial avenue almost a mile long, bounded by ditches.

The siting of the Thornborough Henges, between the rivers Ure and Swale, was also near the gypsum belts. Excavation has shown that the henge builders dug pits to extract the gypsum, which was then used to whiten the banks they had constructed. The three henges (and probably nearby ones, including a now-vanished one at Nunwick immediately north of Ripon) would have shone out brilliantly in the prehistoric landscape. This area is usually interpreted as a ‘sacred’ or ‘ritual’ landscape, though after more than four millennia that can only be speculation.

Article taken from ‘Secret Ripon’ by David Winpenny, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback: ISBN: 9781445672168