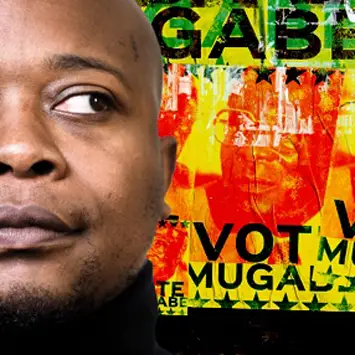

An Interview with Actor & Writer, Tonderai Munyevu

Tonderai Munyevu was born in Zimbabwe in 1982, one of the so-called “born frees” – a member of the generation born after independence. In Mugabe, My Dad & Me – a new one-man play that he has written and performs in – he describes how the first cracks of prosperous Zimbabwe’s decline began to appear in the 1990s, and how he emigrated with his mother to England, where he has since remained. It goes on to reveal how his father lost his job at the hands of a white man, and how this changed both their lives irrevocably, until his father’s death prompted Tonderai to question his identity and what it means to return ‘home’. Interspersing his dialogue with the audience are Robert Mugabe’s speeches: ranging from the 1980s figure in a Savile Row suit, to the bitter and derisive missives from the 1990s, up until 2017 when Mugabe was ousted by a political coup.

What sparked the idea for Mugabe, My Dad & Me?

In November 2017 Mugabe was disposed. That was really the moment I had the first feeling and thought, ‘oh I’m missing it, because I’m not there’. I also had this weird, emotional reaction that I was away from Zimbabwe but also thinking, ‘Oh, he’s not there’. At that point you look at it as a very jubilant turning point. A lot of emotions came out, like when you look at what’s happening in the news with Afghanistan. It’s just so triggering to anybody who has lived through this kind of political turmoil. When big shifting things happen on a political global scale it plays off in real life, rooted in people’s real emotions day-to-day which I find really fascinating.

How did it develop from wanting to tell Mugabe’s story through his speeches?

How did it develop from wanting to tell Mugabe’s story through his speeches?

I quickly realised as I started writing that I needed to put it into context because he’s just a political figure. I didn’t know him personally, so I couldn’t really have a take on him. What I knew was important was to talk about was how Mugabe and his politics had affected my family, and through my family one could see how other families might have been affected. It became important to give it that context.

Is this your first one-man show?

No, I did a one-man show – another macabre piece about Mugabe’s policies, about kicking people from shanty towns. A charity collected seven stories from seven women. The director felt I should be telling the story so I did it as a 35-minute monologue at the Young Vic which was genuinely stressful and terrifying. Performing this (Mugabe, My Dad & Me) is different – I’m completely terrified because it’s such a personal story. And my mom recently passed away so it’s raising a lot of issues. The idea of a one-man show terrifies me but I’m glad to be given the opportunity to do it.

And you aren’t on the stage alone – there’s live music from Millicent Chapanda, who plays the mbira.

I thought it was important to have a female voice, but without having an actual fem voice. It felt it was really about my dad and me. My mother’s in the story but the angle wasn’t about looking at that, but women are so central in the culture that a female ‘voice’ was important to include. Certainly my mother has been central in my personal life, in terms of picking up the pieces where my father left them. And there is a great female icon who was very central to the first war of liberation. So it felt like a very symbolic thing for the play.

How do Millie and her music fit into the play?

Millie represents the rituals of of our culture, especially around death and the celebration of life. She plays a very emblematic and spiritual Zimbabwean instrument. People use it to dance and have fun but it’s really also linked to spirituality and possession.

Did you always know you wanted to act and write?

I grew up always interested in theatre, but, being a child of a migrant, it’s a struggle because I was really bullied at school. My mom also thought, ‘oh great, do theatre because it makes you feel good about yourself, but you should be a lawyer’. I was good at religious studies, so I studied Theology at university. At the end of the degree I was sure I wanted to act so did training with the Actors Company.

You have a theatre company called Jazz Productions – what sort of work do you do?

We perform two man versions of Shakespeare’s plays. I’ve been writing and directing for them for my whole career really, but lately phad a feeling that it’s time for me to really explore my own personal ambitions. I’ve been writing and pitching a lot, and hoping to catch a big fish. And this – Mugabe, My Dad & Me – is a big fish as far as I’m concerned. I’m also part of theatre company Stockroom’s (formerly Out of Joint) writers’ room, which is amazing as I’m employed by them on a salary, which is quite unusual as a writer.

What are your ambitions?

I’m trying to make work that is sustainable, that is thoughtful. It’s really about wanting to make something that five years from now can be put on again and has relevance and significance. That takes time to dig a little deeper to understand what it is that you’re working on, so that it goes beyond yourself.

How did you feel about returning to Zimbabwe recently?

I went on the project so it was really specific and detailed. I’m always happy to be involved, but it’s always an existential thing isn’t it? Always about, ‘Am I good enough to be here? How much of the language have I retained?’. I’m using my own country and my own experiences – what right do I have? Is what I’m saying accurate? I’m super gay and in that environment people treat me as a gay man because they know that I’m not local so they can’t impose what they think. I do worry that I don’t see the country as clearly as people who live there every day. It’s a heightened situation but I’m always glad to be home. It feels different – and not just the sunniness. It just feels where I belong.