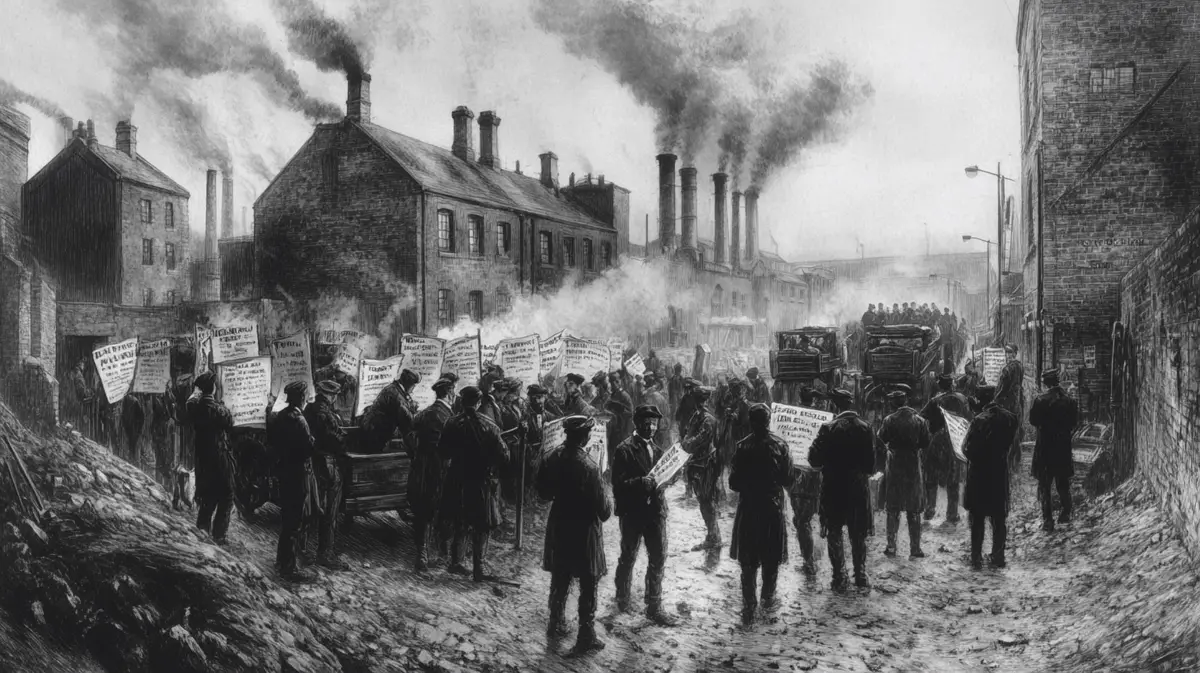

The Leeds Gasworks Riots of 1890

By Harry Bratley

During the summer of 1890, the most brutal street violence in nineteenth-century Britain brought Leeds to a standstill. Factories were forced to close, streetlamps went out, and angry mobs roamed the town in a conflict without parallel in the industrial history of Leeds.

The Gas Committee, which controlled the council-owned gasworks, had in 1889 agreed to an increase in wages and improvements to working conditions, forced by the growing strength of the National Union of Gas Workers. This obliged the council to charge consumers more for gas. However, the Committee had a plan to reverse these union gains and was waiting for the right moment.

Liberal councillor Alderman Gilston suggested that the best time to act would be in summer when demand for gas was lower. In mid-June, without consulting the union, the Committee imposed new working conditions. Notices were posted at all works informing the men that from 1 July they would be required to sign a new contract agreeing to complete 25% more work within their eight-hour shift.

The men refused to sign the new agreement, and on Friday 27 June, they downed tools and walked out.

The Gas Committee had anticipated opposition to their demands and had prepared for a strike. To ensure continuity of supply, they had arranged for replacement workers from London and Manchester. When the strike commenced, agents were dispatched to bring in this alternative workforce.

The strikers soon discovered the Committee’s plan. Union leaders directed members to prevent the ‘scabs’ from reaching any of the gasworks. Pickets were doubled and installations strongly guarded.

“Increased force”

The first clash occurred on Monday 30 June. To accommodate the new recruits at Meadow Lane works, a marquee was to be erected in the yard. When a wagon arrived with the tent and provisions, the crowd recognised its purpose, dragged the delivery men from the cart, and beat them. Vastly outnumbered, the police escorts were unable to intervene.

As the situation descended into riot and mob rule, the Chief Constable was ordered to ensure the tent’s delivery that night. With an increased force of over seventy officers, the wagon approached the works at 9pm. The expanded police presence allowed it through with only some booing and stone-throwing.

That same night, the first replacement workers arrived by train at the railway goods station across the road from Meadow Lane works and were quickly settled in. The Gas Committee’s phase one was complete. The next phase, however, would prove far more difficult—and dangerous.

Word spread that more recruits from Manchester were arriving at 4am on Tuesday. A huge crowd awaited the train. Unable to take the new men directly to the gasworks, police had to march them through thousands of protesters and house them in the Town Hall. Protesters surrounded the building, determined to prevent the non-unionists from being moved. Fearing they would be overwhelmed, the Council summoned Dragoons from York and additional police from nearby towns.

Meanwhile, at Meadow Lane, the new workers from London had started work. The crowd outside feared gas production would soon resume. Union officials scaled the yard walls and appealed to the new men to stop work. When the circumstances of the lockout were explained, the new recruits realised they had been misled and wanted to leave—but feared the crowd outside would attack them.

After guarantees of safe passage were given, they exited the gates to cheers and were escorted to union offices in Kirkgate. Representatives told the Gas Committee they had been misled and demanded their fares home. The request was refused, and the men were told to make their own way back. That evening, some were seen walking through Pontefract—on foot, without fare money.

“Insulted”

With the replacement workers no longer in post, gas supplies fell critically low. Industries shut down. In clothing factories alone, as many as 20,000 people were idle. Anger against the authorities intensified, placing the Gas Committee under extreme pressure to reinstate gas supply.

At dawn, the Town Hall remained surrounded. Union leaders instructed the crowd not to leave until the ‘scabs’ emerged—and to stop them, by any means necessary, from reaching the works.

At 8am, under heavy police and military escort, the new recruits set out for the New Wortley Gasworks on Wellington Road. Public hostility was palpable: the crowd numbered more than 30,000. The men were jeered, spat at, and insulted, but the soldiers hemmed them in.

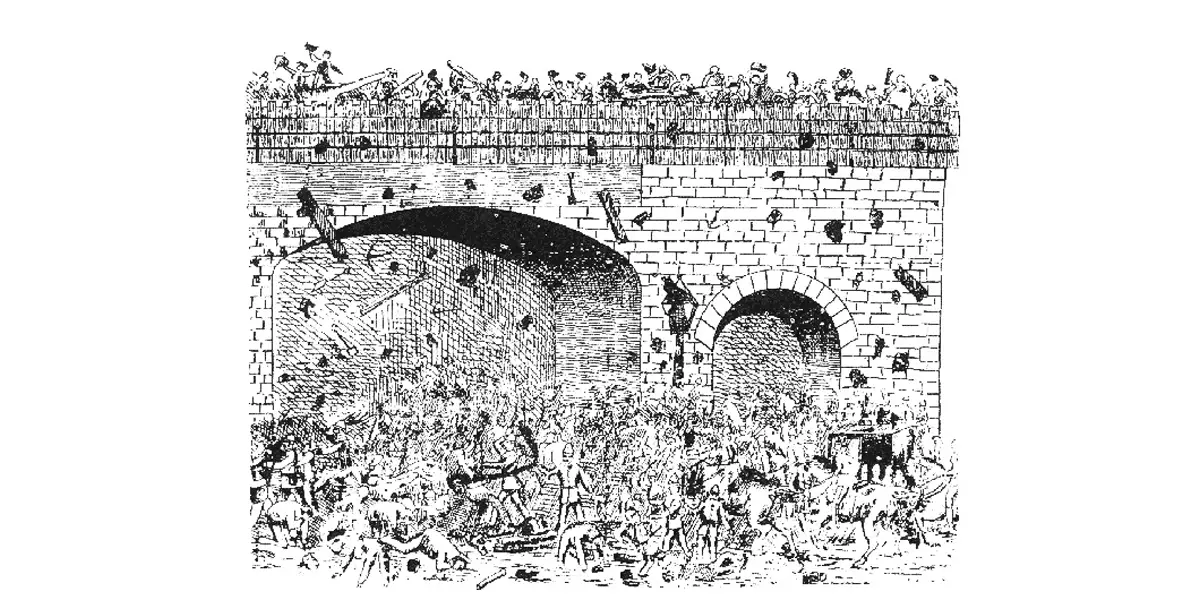

As the column neared New Wortley Railway Bridge, everything collapsed into chaos.

The strike leaders had identified the bridge’s height as a strategic point of attack. As the column approached, the crowd—estimated at 15,000—assailed them from above with bricks, stones, iron belts, and other heavy missiles.

One report described the scene:

“The bridges were crowded with men… and they massed piles of missiles. As they came within range, the fire was directed with simply terrific force on them. The scene that ensued defies description. Bricks, stones, clinkers, iron belts, sticks, etc., were hurled into the air to fall… upon and amongst the blacklegs and their escort.”

“Scaled the wall”

Those below were helpless. Many were badly injured. The military drew their swords and charged, but the crowd fought back. Soldiers were dragged from horses, trampled, kicked, and beaten. Eventually, the military and police forced their way to the gasworks gates, forming a shield through which the workers could run inside.

One union man described it:

“The soldiers made guard by the gates, but as soon as they were opened and the blacklegs made to enter, the crowd rushed in. I was with them. We charged at the blacklegs, who in their terror made a rush for the wall, over which many escaped. The police counter-attacked. I received a terrible blow on the back of the neck and went down like a bullock.”

The police eventually secured the gates with the remaining new workers inside. Tens of thousands outside screamed in frustration. Inside, the recruits were terrified, doubting the authorities’ ability to protect them.

Protesters climbed the walls, calling down to reassure the men that their quarrel was not with them, but with the Committee. One by one, the workers scaled the wall and fled, cheered by the crowd. More than half left. The Committee may have succeeded in getting them inside—but not in keeping them there. Gas supplies would not resume as easily as hoped.

In a jubilant show of solidarity, the men who fled were paraded to Town Hall Square, where a mass meeting took place. They said they had been misled and were unaware they had been hired to replace strikers.

“Arbitration talks”

That night, another violent episode erupted at Meadow Lane. Up to 15,000 people gathered outside, hurling bricks and bottles at police. As the mob surged, the police responded with batons and drove them back. The Yorkshire Post reported many serious injuries. An innocent bystander recounted:

“I reached the works when the police arrived and stood in the crowd. The policemen began pushing the people back, but the crowd would not move. The police began hitting anyone they could with their staves. They used their weapons freely on anyone—women and children included. I was struck half a dozen times, my head was split open, my face covered in blood. I had done nothing.”

By the end of the night, more new recruits had fled. Many spent the night at union offices and left the next day with union-paid tickets.

On Tuesday, the Town Council criticised Alderman Gilston for mishandling the situation. He defended himself, saying he had acted in the public interest.

The Chamber of Commerce hastily convened arbitration talks between the union and the Committee. Though no resolution was reached that day, both parties agreed to reconvene the next.

That evening, tensions again escalated. At Meadow Lane, a small group of non-unionists continued fuelling furnaces. Fearing that gas production might resume, the crowd outside grew and began hurling missiles over the wall. The police retaliated, charging the crowd and driving them back—though not before protesters tore off one of the gates and carried it away triumphantly.

At New Wortley, gas production had barely resumed. Despite a strong police presence and new barricades, rumours of an imminent assault persisted. The Chief Constable ordered officers to arm themselves with cutlasses. The Mayor arrived, read the Riot Act, and warned that anyone remaining in an hour would be shot. By the time the Dragoons arrived, the protestors had dispersed.

By Wednesday, opinions on the Committee were divided. Some still wanted to send more recruits; others saw that the battle was lost. Rumours of legal action from local businesses reinforced their weakened position. A settlement had to be reached.

Talks resumed the next day. After lengthy discussions, the union secretary announced an agreement had been reached. He told around 500 men assembled at the union office that:

The requirement to sign the new contract had been withdrawn.

Withheld wages would be paid.

In his view, the Committee had “totally surrendered”.

“Momentous victory”

The men accepted the outcome, but one issue remained: the ‘strangers’ still inside the gasworks. The workers refused to return unless all outsiders left.

This posed a problem. The Committee had legal obligations to the replacement workers—some had twelve-month contracts. The union insisted it was not their concern: the ‘scabs’ had to go.

A Committee delegation visited Meadow Lane and offered the recruits a severance deal: train fare home and a lump-sum payment. The offer was accepted. The same deal was offered at New Wortley. By 5pm, the last of them had departed on the express train to Manchester.

With the outsiders gone, the Leeds gas workers returned. The dispute was over.

But recriminations followed. Local papers, townspeople and unions criticised the Committee’s handling of events and the financial cost. What had been launched to save ratepayers’ money had ended up costing them around £20,000. The Liberal councillors responsible were decisively defeated in the next election.

The strike had been a momentous victory for the workers. It came at a time when the union movement was under heavy attack. In East London, a similar dispute had seen the union crushed. In Leeds, the strategy of importing strike-breakers and using force had failed.

The press, particularly the Leeds Mercury, was not pleased:

“Strikes are assuming a new character. The gas men have not only realised their commanding position, they have committed to an armed battle with authorities—and won.”

The Times was even more scathing of the authorities:

“The Gas Committee entered a battle it could not maintain and has been forced to surrender. It has been a bad business for Leeds—costly in cash and full of public inconvenience.”

This was a defining moment for New Unionism and the power of organised labour. The involvement of other trades and use of secondary picketing had shifted the balance of power, demonstrating the effectiveness of collective action in industrial Britain.

images are representational