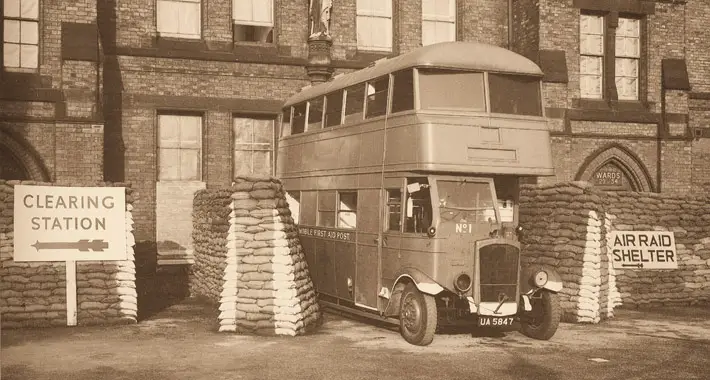

The Leeds Blitz of 1941

By Harry Bratley

During the Second World War, Leeds was an important producer of aircraft, tanks and ammunition, as well as being a major manufacturer of textiles, and the city would have been a strategic focus for German air attacks. Among the targets would have been the Barnbow munitions factory at Crossgates and, undoubtedly, the Avro factory at Yeadon, where Lancaster bombers were being built for the Royal Air Force – both, surprisingly, were left untouched during raids on the city.

There were a total of nine air raids on the city by the German Luftwaffe, with the most devastating attack being on the night of 14–15 March 1941, named the ‘Quarter Blitz’, when 40 enemy aircraft unloaded more than 25 tons of bombs over a large area, including the city centre. Over 4,500 buildings were damaged, 65 people were killed and 258 were injured.

Air-raid sirens started sounding at 9 pm when German bombers were detected crossing the east coast, signalling a possible attack on Leeds. Air-raid wardens – whose main task was to protect people during raids when enemy planes dropped bombs – would have been the first to respond that night, with over 4,000 on duty, most of them part-time volunteers. By the end of the night, four wardens had been killed and seven severely injured.

Leeds was indeed the target that night and, by midnight, the streets around Water Lane were alight. Leeds Museum, Mill Hill Chapel, the Royal Exchange Building, Denby & Spinks furniture store and the Yorkshire Post offices (then on Albion Street) were among the buildings in the city centre that were hit. The raid continued with more bombs dropped at Gipton, Headingley and Roundhay Road, followed by further damage on Wellington Street, the Central and City railway stations, the Metropole Hotel on King Street and Quarry Hill Flats.

“Explosives and incendiaries”

German bombs damaged several thousand houses across Leeds during the raid, and the Fire Service dealt with 116 fires throughout the night, with 85 members of the Service injured. Members of the Ambulance Service were also hurt, with one ambulance worker killed and five more injured. Luckily, by the time of this particular raid, many private and public air-raid shelters had already been erected in Leeds, which would have saved many lives.

Press-censorship laws prevented newspapers, including the local press, from reporting any details that might be of use to the enemy, and the mention of specific towns or cities was prohibited. The Yorkshire Post headlined the air raid on Leeds as ‘NORTH-EAST TOWN’S LONGEST ATTACK’, reporting that raiders passed over in waves and were engaged by ground defences, the barrage being one of the most intensive since the outbreak of war. It also commented that many of the high explosives and incendiaries were dropped on residential areas and that, having regard to the intensity of the raid, casualties were not unduly heavy. However, the effect of the raid could not be concealed from the citizens of Leeds. The first funerals of those killed took place four days later, when five victims of the air strike were buried at Harehills Cemetery, attended by the Lord Mayor, Alderman Withey.

“Shadow factory”

There was one interesting survivor of the raid that night. The German bombardment took out the old Leeds Museum on Park Row and many of the exhibits were completely destroyed, including two Egyptian mummies. However, one mummy did survive – that of Nesyamun, the high priest of the Temple of Amun in Luxor, the largest religious building in the world – a gift to the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society in 1824 by John Blaydes. The mummy and the coffin were blown out into the street but, even though the inner coffin lid had been smashed, the remains of Nesyamun were remarkably untouched. So, 3,000 years after his life ended, you can still see him on display at Leeds City Museum, which today stands on Millennium Square.

Although many parts of the city were devastated by the Blitz, the German Luftwaffe failed to find the main prize: the Avro factory at Yeadon, built in 1939 alongside what is now Leeds Bradford Airport. The factory produced Lancaster bombers used in the legendary ‘Dambusters’ raids that destroyed three dams on the Ruhr in Germany in May 1943. Covering 1.5 million square feet, it was the largest single factory unit in Europe at the time. So why did the Germans miss such a large industrial area? The Avro works were what was known as a ‘shadow factory’. To avoid air strikes, the roof was camouflaged with fields, hedgerows, dummy buildings and even a duck pond. Hedges and bushes made of fabric were changed to match the colours of the seasons, and personnel moved dummy animals around daily to enhance the camouflage. It worked: enemy bombers never detected the aircraft-manufacturing plant.

“Dust and smoke”

A diary by Arthur White, written for Mass-Observation, a UK social-research project, gives an insight into how the Blitz affected the people of Leeds after the raid. White lived on Beeston Road and owned two men’s clothing stores. His diary entry for 15 March 1941 is peppered with fragments of conversation taken from the people around him, revealing not only how he felt but how many others were feeling too. On the bus into town, White tells of the ‘whispering, and the movement of bodies’, then the remark that ‘Leeds has caught it at last’, implying that many thought it would only be a matter of time before the city fell victim to a heavy bombing raid. He also describes the bomb damage, noting ‘buildings with all their windows blown in, roadways full of broken glass and a lingering smell of dust and smoke everywhere’. He touches on the human cost, with someone talking about eight deaths in their area, rescue crews searching for bodies, and how uncomfortable the destruction, death and shock had left him feeling – claiming that the situation made him and others feel on edge, worried and ‘restless’.

Government and press messaging often suggested that, no matter what the damage (frequently claimed to be minimal), the British people would emerge stronger than ever. White’s reflections suggest otherwise. Many had died or were left with serious injuries, a large number of buildings in the city centre were hit, and everyone was clearly shaken by the events. The war impacted heavily upon the people of Leeds, who supported the country’s military efforts with manpower, machines and money, and directly experienced the fears and losses caused by raids. For the people of Leeds, this was one battle they all had to endure on that devastating night.

Top image is representational

![Merlin [Northern Ballet] – Review – Sheffield Lyceum (3)](https://www.on-magazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Merlin-Northern-Ballet-–-Review-–-Sheffield-Lyceum-3-150x100.jpg)