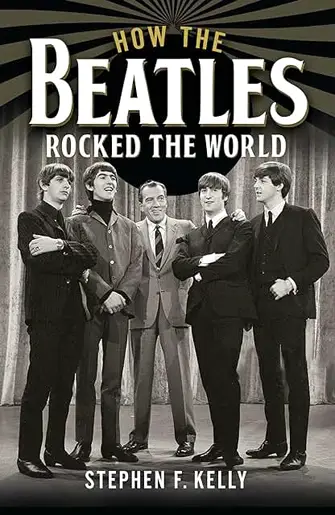

How The Beatles Rocked the World by Stephen F. Kelly – Review

By Clare Jenkins

The old saying is ‘If you can remember the Sixties, you weren’t there’. Stephen F. Kelly remembers them. As a teenager in Birkenhead at the start of this transformative era, he recalls going to the Cavern in Liverpool’s Mathew Street and seeing not just The Beatles but also The Searchers, The Merseybeats and The Rolling Stones.

Years later, on a trip back to the basement nightclub with German friends, he’s overcome with nostalgia: ‘It is as if I am a teenager again’, he writes, ‘rebelling against the old order, desperate to escape suburbia and my dreary job in a shipyard and make something of my life. I was a typical child of the time, not unlike Arthur Seaton in Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, a teenager and a bit younger than Seaton, but not giving a damn, just wanting to change the world. And that world was indeed ready for change.’

Central to that change, according to Kelly, were The Beatles, whose story is threaded throughout this pacey, informed and informative social history of the decade.

The generation they belonged to had pretty much escaped the war (and National Service), unlike their parents. They wanted things to be very different: peace, a voice, better education, wider opportunities, freedom… ‘It was an era,’ writes Kelly, ‘when young people seized the initiative from an older generation, challenging authority and changing attitudes. They confronted the political ideologies of the past with their new radicalism, throwing out the social mores that had made life restricting for so many women, gay people and couples trapped in unloving relationships. They generated new ideas in art, music, drama, books and television, and even provoked the established religious orders in their search for new spiritual meanings.’

And there were a lot of them: five million teenagers were living in Britain at the start of the decade, thanks not least to the immediate post-war baby boom. As the decade unfolded, attitudes previously set in stone started to crumble: unquestioning respect for authority figures and institutions, including the Catholic (and Anglican) Churches, acceptance of a hierarchical political system that wouldn’t let you vote until you were 21, the sense of forelock-tugging subservience that implied you should know your place in society. In came irreverence, social mobility and disobedience: Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s ‘winds of change’ started to blow through not just the UK but throughout Europe, the Empire, the USA – even, eventually, through the Soviet Union.

It’s a broad sweep and much has been written on the subject before, not least by Dominic Sandbrook in White Heat. But by using The Beatles as the bedrock, Kelly makes the case for the ‘Fab Four’ being at the heart of the seismic changes in society.

He quotes an American journalist: ‘With their music, their very presence, their humour, their wit, their good looks, everything about them, they helped the United States emerge out of that period of mourning [after the murder of President Kennedy] and really touched off the Sixties as we think of it.’

His German friend agrees: ‘The Beatles changed our society. After the war we were so repressed. There were things we didn’t mention, questions we daren’t ask. But the Beatles released us from that straitjacket and young people began to talk about these things.’

‘These things’ included sex, of course, which was suddenly everywhere, in many forms. As poet Philip Larkin famously wrote: ‘Sexual intercourse began/ In nineteen sixty-three/ (which was rather late for me)/ Between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban/ And The Beatles’ first LP.’

“An age of radicalism”

It surfaced in politics (the Profumo scandal), in TV dramas like the Play for Today and Wednesday Play slots, in theatre productions such as Hair and Oh! Calcutta!, in books like Lady Chatterley’s Lover (subject of the famous obscenity trial) and Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction, in films like Alfie and The L-Shaped Room, and of course in real life. Though, with the new contraceptive pill initially only prescribed to married and engaged women, illegal abortions were widespread in the UK, with numbers ranging from a conservative 54,000 each year up to 250,000.

It surfaced in politics (the Profumo scandal), in TV dramas like the Play for Today and Wednesday Play slots, in theatre productions such as Hair and Oh! Calcutta!, in books like Lady Chatterley’s Lover (subject of the famous obscenity trial) and Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction, in films like Alfie and The L-Shaped Room, and of course in real life. Though, with the new contraceptive pill initially only prescribed to married and engaged women, illegal abortions were widespread in the UK, with numbers ranging from a conservative 54,000 each year up to 250,000.

Where homosexuality was concerned, Basil Dearden’s film Victim was the first English-language film to use the word. Ironically, the gay barrister faced with blackmail was played by Dirk Bogarde, himself a ‘closet gay’. The Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein found himself one of a number of high-profile men to be prosecuted for ‘indecent acts’. At least they weren’t subjected to ‘cures’ that included electric shock aversion therapy.

Both main churches had to re-examine their attitudes towards these and other social issues. No wonder, then, that when The Beatles discovered India, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and meditation, so many young people followed in their footsteps, both literally and metaphorically.

The Sixties was an age of radicalism throughout society: on the streets, in the ‘new’ universities (where pioneering Sociology degrees became popular), in the showing of Cathy Come Home on TV; an age of Angry Young Men (and women) writing books (Stan Barstow’s A Kind of Loving, John Braine’s Room at the Top) and plays (John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mr Sloane).

It was an age of pirate radio, poets, Private Eye and Pop artists like Peter Blake (who designed the Sgt Pepper album cover) and Pauline Boty; of fashion designers Mary Quant and Ossie Clarke; models Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton, photographer David Bailey, Cathy McGowan and TV’s Ready, Steady, Go. Of Teddy Boys, Beatniks, Mods & Rockers; of cannabis, Purple Hearts and LSD; of Labour’s Harold Wilson in Downing Street, George Best (‘the Fifth Beatle’) on the football pitch; an age of protests against the Vietnam War and the nuclear threat, and in support of CND, Women’s Lib and Black Power; an age which saw the abolition of the death penalty and the overhaul of same-sex and abortion laws.

So this is a wide-ranging book, but Kelly always manages to bring it back to The Beatles. What they did, he writes, ‘was to give hope to a generation. If they, four working-class lads from the North, could make it, then almost anyone could, no matter what school you had been to.’

It may have been Bob Dylan not The Beatles who sang ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’’, but they were, and they did.

‘How The Beatles Rocked the World’ by Stephen F. Kelly, is published by the White Owl imprint of Pen & Sword Books, £25 hardback