The Rise of the Sheffield Heavy Steel Industry and the Expanding Retail Sector

By Melvyn & Joan Jones

The heavy steel and engineering industry was a relative newcomer to Sheffield. It did not emerge on any appreciable scale until the 1850s, but by the end of the nineteenth century had overtaken the light steel trades and had resulted in the vast physical expansion of the urban area and explosive population growth.

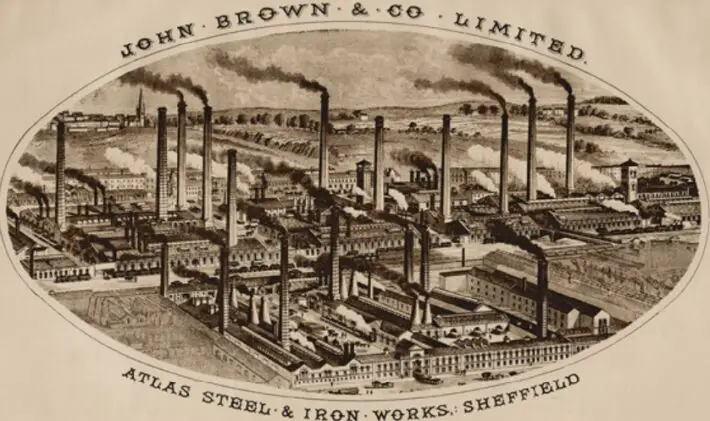

The new industry was based on the insatiable market that had arisen for machine parts, axles, tyres, boilers and springs for the railways, steel for guns and shells, and plates for ships. To meet the rapidly growing demand, light steel firms – including what were to become household names later in the century, e.g. John Brown (who started as a cutler), Charles Cammell (file-maker) and Thomas Firth (file, saw and edge toolmaker) – set up new works to manufacture steel on a bigger scale.

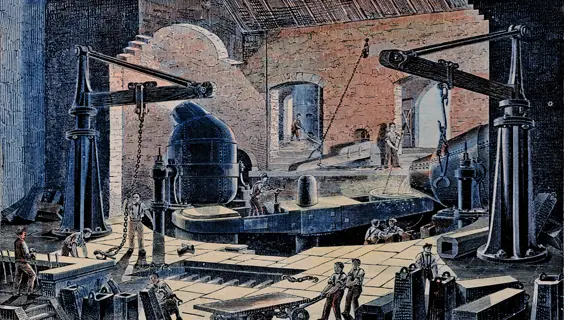

Throughout the 1850s, before the adoption of the Bessemer process, the only way of producing the large ingots of high-quality steel required by the market was to assemble in one work large numbers of converting (cementation) furnaces, crucible holes, and puddling furnaces (for making wrought iron for plate production and puddled steel). This naturally led to the growth of large new steelworks. These were mostly built on ‘greenfield’ sites in the wide Don Valley to the east of the town in Brightside and then Attercliffe.

“80–90 per cent of British steel-making capacity”

There was flat land beside the river for the construction and subsequent expansion of the large works and in the surrounding area for houses for the workers, who were attracted in large numbers. In addition, there was a constant supply of water from the River Don and access via the Sheffield & Rotherham Railway and its branch lines to the coking coal from local collieries, and to the pig iron from the Continent.

The new industry also took advantage of good locations beside the Manchester–Sheffield Railway to the north-west of Sheffield in the villages of Owlerton, Wadsley, and Oughtibridge, and even Stocksbridge on the Little Don where Samuel Fox had set up his works in 1841.

It has been calculated that the light and heavy steel trades of the Don Valley between Stocksbridge in the north-west, round the elbow bend and through Sheffield, past Rotherham to Swinton, accounted for 80–90 per cent of British steel-making capacity in the early 1850s.

“Six tons of cast steel in around thirty minutes”

The Bessemer converter made its first appearance on Carlisle Street at Bessemer’s Steel Works in 1858, in the very midst of the new steelworks with their many cementation furnaces and crucible holes. This was a radical step by its inventor Henry Bessemer following the sceptical reception of the new invention that arose from doubts about the process itself and about the quality of the large amounts of steel that were produced in such a short space of time. Traditional methods of converting pig iron into blister steel and then into crucible steel took fourteen or fifteen days to produce a 40–50 pound ingot of cast steel, whereas the Bessemer process could produce 6 tons of cast steel in around thirty minutes.

Two of Sheffield’s major new firms, John Brown’s and Charles Cammell’s, became the earliest converts and produced their first Bessemer steel rails in 1861, followed by Samuel Fox in 1863. By the first decade of the twentieth century there were at least eight heavy steel firms each employing more than 2,000 workers and six firms employing between 1,000 and 2,000 men. The biggest concentration of the heavy steel and engineering industry was in Brightside and Attercliffe – the ‘East End’ of Sheffield.

The beginnings of this massing together of the new industry had been evident in the 1850s, but by the beginning of the twentieth century it was no longer a thin and broken line of industrial premises but an almost solid mass of works and railway sidings surrounded by rows of terraced houses. The greatest concentration of works began within half a mile of the city centre along Carlisle Street and Savile Street. This complex included Charles Cammell’s Cyclops Works, John Brown’s Atlas Works (both works appropriately named after giants of Greek mythology), Henry Bessemer’s Steel Works and Thomas Firth’s Norfolk Works, with the railway running beside and between the works.

“Increasingly concentrated on armament production”

The new steelworks attracted to the east end of Sheffield a rapidly growing population. Brightside’s population trebled between 1841 and 1861 (from 10,089 to 29,818), doubled by 1881 (to 56,719) and had reached 75,000 by the end of the century. Attercliffe’s population growth was not quite on the same scale but still impressive: from 4,156 in 1841 to 7,464 in 1861 then a giant leap to nearly 30,000 in 1881 and to nearly 52,000 in 1901. And a great number of the new residents of Brightside and Attercliffe, and Burngreave, Grimesthorpe and Darnall, were in-migrants from near and far; for example, a study of the inhabitants aged fourteen years and over living in ninety-four houses in Forncett Street in 1871 within a stone’s throw of three important steelworks belonging to Henry Bessemer, John Brown and Charles Cammell showed that 85 per cent (408 out of 449) were migrants.

After the re-equipment of the railways in Britain with steel rails, rail manufacture tended to move to the coasts from where overseas markets could be more easily served. Although the unfavourable locational circumstances checked the production of commongrade steel in Sheffield, they did not check the development of the industry; they merely diverted development into new channels, namely the production of steels where the cost of manufacture and the value of the product far exceeded the cost of raw material assembly and distribution, and in whose making scrap could be extensively used.

Specialisation became the keynote of the heavy trades and the research laboratory became an important factor in the Sheffield steel industry after 1880. The most famous names in the industry increasingly concentrated on armament production, John Brown’s and Cammell’s increasingly specialising in the manufacture of armour plate, and Firth’s on gun barrels and armour-piercing shells. Before the First World War Sheffield was ‘the greatest Armoury the world has ever seen’.

“193 firms in the city engaged in refining and manufacturing steel”

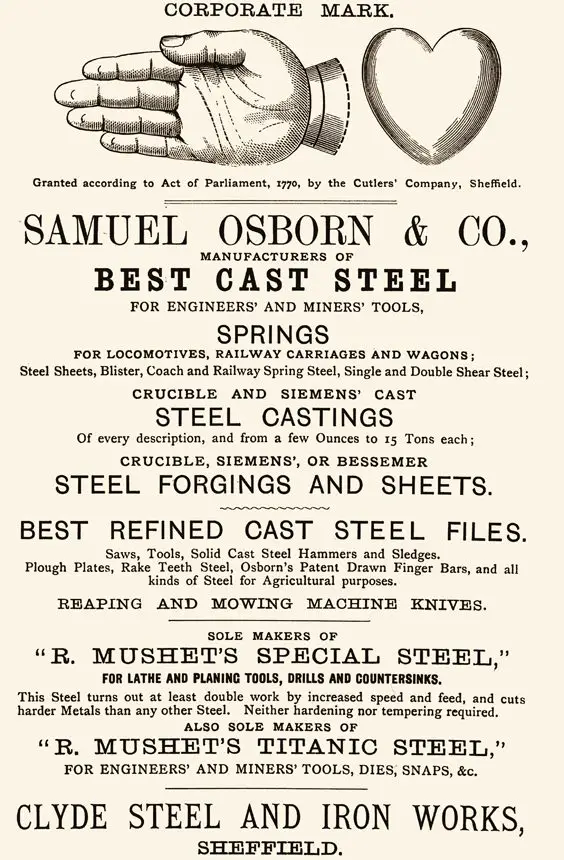

Other firms also increasingly concentrated production on specialised products. For example, Samuel Osborn’s specialised in cast steel ‘of every description from a few ounces to 15 Tons each’ and were the sole manufacturers of Mushet’s ‘special steel’ and ‘titanic steel’ used in the manufacture of specialised tools, drills and dies; Jessop’s specialised in cast steel for engineering, machinery and edge tool purposes; Jonas & Colver’s specialised in steel for small arms manufacture; and W. T. Beesley manufactured steel to a quarter of a thousandth of an inch in exactness. John Brown’s, Cammell’s and Vickers also had shipyards at the coast and in 1910 it was claimed that all three firms were capable of ‘turning out a battleship complete’.

By the beginning of the First World War, in spite of the steady expansion of the light steel trades the heavy steel trades dominated industry in Sheffield. Between 1891 and 1911 employment in steelmaking had increased by 50 per cent and in engineering by more than 80 per cent. There were 193 firms in the city engaged in refining and manufacturing steel, forty-one firms engaged in rolling and forging steel and there were thirty-three foundries. But as in the first half of the nineteenth century, it was not just the steel industry that expanded.

“Firm is still going strong today”

In the early 1840s George Bassett started his liquorice sweets business and by 1862 he employed 150 workers making delicious liquorice comfits, candied peel and Pontefract cakes. Later, of course, the firm ‘invented’ Liquorice Allsorts. This came about, apparently, when a ‘rep’ was visiting a customer and an assistant accidentally dropped a tray of samples onto the floor. The customer liked the assortment, and so Liquorice Allsorts came into being.

In the 1920s the Bertie Bassett trademark was designed and with minor alterations is still being used. The firm is now part of the Maynards Bassetts group. In 1883 one of the best-known food product firms was established – Henderson’s Relish, Sheffield’s answer to Worcester Sauce. The firm is still going strong today. And in 1895 William Batchelor founded Batchelor Foods, which for many years occupied a factory at Wadsley Bridge, in the upper part of the Don Valley.

The firm became famous for the production of processed peas (including ‘mushy peas’) and Cup-a-Soup. And for a short period between 1908 and 1925 Sheffield had its own car industry. Simplex cars, owned by Earl Fitzwilliam of Wentworth Woodhouse, produced luxury cars and motorcycles.

“Booming town”

Considerable expansion also took place in the retail sector as Sheffield’s population grew and grew, and by the end of the nineteenth century the retail core stretched for more than a mile from Haymarket in the north to the bottom of The Moor in the south. By the 1850s Sheffield had a number of markets across town. The Norfolk Market Hall opened in 1851 on Haymarket with money given by the Duke of Norfolk. The hall was 296 feet long and 115 feet wide with stalls and shops around an enormous fountain. On sale were fruits, vegetables and confectionary.

There was also the Smithfield Market for cattle, hay and agricultural implements and the Sheaf Market for agricultural and market garden produce together with poultry, rabbits, dogs and birds. The Fitzalan Market Hall sold meat, fish, game, poultry and butter.

By the 1870s Sheffield also had two co-operative societies. Serving the northern part of the town, the Brightside & Carbrook Co-operative Society was established in 1868 and by 1914 had 29,000 members. The Sheffield & Ecclesall Co-operative Society, originating in the Ecclesall Road area in 1874, also expanded quickly and by 1925 had twenty-nine grocery branches. By that time there were also four department stores in the booming town.

“Kept expanding”

The first one was Cockayne’s established in 1829 by Thomas Bagshawe Cockayne and his brother William. It started as a draper’s store before becoming a large department store on Angel Street by the end of the century. Meanwhile Cole Bros (now John Lewis) was established at No. 4 Fargate (Cole’s Corner) in 1847. It was owned by three brothers – John, Thomas and Skelton Cole – who were described as ‘silk mercers and hosiers’. They extended the original shop along Fargate and round onto Church Street and began selling a wider range of goods including shawls, bonnets, furnishings, carpets and sewing machines.

Cole’s Corner, as the area came to be known, was a favourite meeting place and the title of a Richard Hawley album. Atkinson’s, which is still going strong as an independent family store, began as a small drapery store on The Moor in 1872. John Atkinson, who started the business, specialised in hosiery, ribbons and lace. Over the next thirty years business kept expanding both in floor space and the range of goods on offer and by 1902 the original premises had been demolished and a new purpose-built store erected.

John Walsh, who had worked as a shop assistant at Cockayne’s, opened his first store in 1875 and in 1899 opened his purpose-built store on High Street that was five storeys high, covered more than 3 acres and employed over 100 members of staff.

Article taken from ‘Sheffield at Work: People and Industries Through the Years’ by Melvyn & Joan Jones, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445677538

Article taken from ‘Sheffield at Work: People and Industries Through the Years’ by Melvyn & Joan Jones, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445677538

Great article! Well written. I love stuff like this, thank you Sheffield’s industrial history is fascinating but taken for granted I think, too easy forgot (helped by Council flattening physical remains, entire communities, since 1950s) Also too easy to forget UK’s wealth was built on the backs of the working poor, who had sadly little to show for it; dying young – no H&S – or in workhouses, no money for Drs or to stop 100,000+ pauper children being trafficked as ‘indentured servants’ – child slaves – to Canada, should one parent should die or fall on hard(er) times, by corrupt mercenaries and arrogantly deluded do-gooders; ‘No room for these little ones on our crowded isles’-! = ‘UK happy to take profit from w’class but not to give any duty of care to their offspring, and the Colonies want cheap/child labour’. Never forget how much better things are for us, thanks to those who fought for it, or how grotesquely bad life was for most who made Steel City.