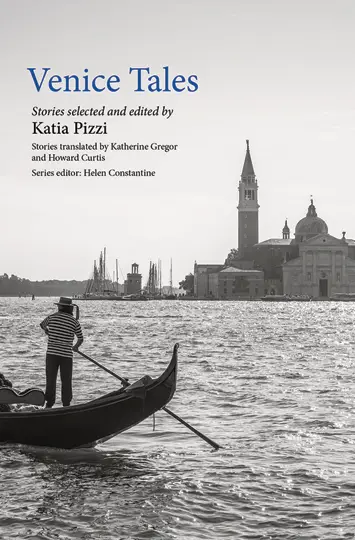

Venice Tales, Stories Selected and Edited by Katia Pizzi – Review

By David Schuster

I’ve only spent a single day in Venice but, like so many others over the centuries, I fell under its spell. Somehow, every alleyway and tiny square backed by a baroque church holds the promise of mystery. Managing to be both grand but faded, elegant but shabby, La Serenissima is a uniquely alluring city. It was the desire to feel something of that magic again that made me want to read Venice Tales, a collection of short stories edited by Katia Pizzi.

This book’s point of differentiation from others on the subject is that the tales – some factual, some fiction – were all written by Italian authors. The translation into English, by Katherine Gregor and Howard Curtis, is expertly done, capturing the nuances of language with the beauty and flow that you’d normally associate with your native tongue. The Italian viewpoint perhaps provides a more grounded, prosaic view of the Floating City.

The writers span almost the whole of Venice’s history, from the Middle Ages to the present day, and Pizzi has chosen to present the book chronologically. To arrange any collection of entertainment – be it written or music – by creation date always strikes me as ill-advised. The consumer is thus presented with the oldest, and least familiar, style first. I read a lot of Victorian fiction, which many find too slow and florid for modern tastes, but I admit that I struggled with the first of the tales. This extract from Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio is, at its heart, an extremely humorous satire on deceit and gullibility. However, it was written in 1353, and for me at least, the archaic phraseology gets in the way of the story.

It’s lucky, then, that the editor has included such a comprehensive and enlightening introduction. In this, each of the articles is described in detail, providing some fascinating background. What is especially useful is that Pizzi also offers comparisons between the stories – similarities and differences. I strongly recommend reading the introduction, and using this to identify those narratives which most call to you. In this way, I selected A Ghost in Venice, Silver and The Man Who Sleeps in Churches as most appealing to me, and read these first. I’d then encourage you to read the rest, skipping about, using the introduction as your guide. In this way – as from wandering off the tourist trail – you’ll encounter wonders and horrors which you might otherwise have passed by.

“Spirit of the city”

A Ghost in Venice, Silver and The Man Who Sleeps in Churches are all fiction, written in this millennium. As the name suggests, the first of these is a paranormal anecdote, but with a nice M. Night Shyamalan-style twist. Silver is an achingly beautiful love story, cleverly capturing the poignancy of returning to both a person and a place left behind. The Man Who Sleeps in Churches is something more unusual, capturing the excitement and fear that drives some people to spend the night, without permission, in public spaces – churches, libraries and museums. An unusual hobby, and one I was previously unaware of.

A Ghost in Venice, Silver and The Man Who Sleeps in Churches are all fiction, written in this millennium. As the name suggests, the first of these is a paranormal anecdote, but with a nice M. Night Shyamalan-style twist. Silver is an achingly beautiful love story, cleverly capturing the poignancy of returning to both a person and a place left behind. The Man Who Sleeps in Churches is something more unusual, capturing the excitement and fear that drives some people to spend the night, without permission, in public spaces – churches, libraries and museums. An unusual hobby, and one I was previously unaware of.

Generalising, the fiction works better than the factual articles, mainly because the former are complete, whilst the latter are parts of larger works. Of these, the extract from infamous lover Casanova’s The Story of My Life is the most fascinating. This details his daring escape from the attics of the Doges’ Palace, which adventure highlights the practical difficulties of having a dungeon in a city with no cellars. Conversely, I’d challenge the inclusion of the chapter from Of Venetia, the Noblest City, Francesco Sansovino’s 1581 work, which reads like an exhaustingly over-enthusiastic historical treatise.

Sitting somewhere between the poles of fact and fiction lie the curious chapters from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Reminiscent of The Arabian Nights, this story-within-a-story imagines a meeting between Marco Polo and the Chinese Emperor Kublai Khan. At the Khan’s command, Polo relates tales of places he visited, or heard of, on his travels. Many of these are fantastical, but each contains within it allegorical references to aspects of Venice, his beloved birthplace.

Despite these criticisms, the spirit of the city – both good and bad – gleams from between the lines, and you are left with a much better understanding of it than you would get from any guidebook.

So yes, Venice Tales did help me recapture a little of the magic of my brief visit. But more than that, this is a book that should be dipped into and considered – it will reward your efforts.

‘Venice Tales’, Stories Selected and Edited by Katia Pizzi, is published by Oxford University Press

![Merlin [Northern Ballet] – Review – Sheffield Lyceum (3)](https://www.on-magazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Merlin-Northern-Ballet-–-Review-–-Sheffield-Lyceum-3-150x100.jpg)