The Leeds Military Riot of 1844: When Soldiers Fought the Police

By Harry Bratley

In June 1844, a fracas known as the Military Riot was probably one of the most unusual disturbances ever to take place in Leeds – a mass revolt against the town’s police force. Soldiers fought the police, and the police battled with both soldiers and townspeople. The unrest continued for three days and ultimately resulted in the complete removal of the 70th Foot Infantry Regiment from the town.

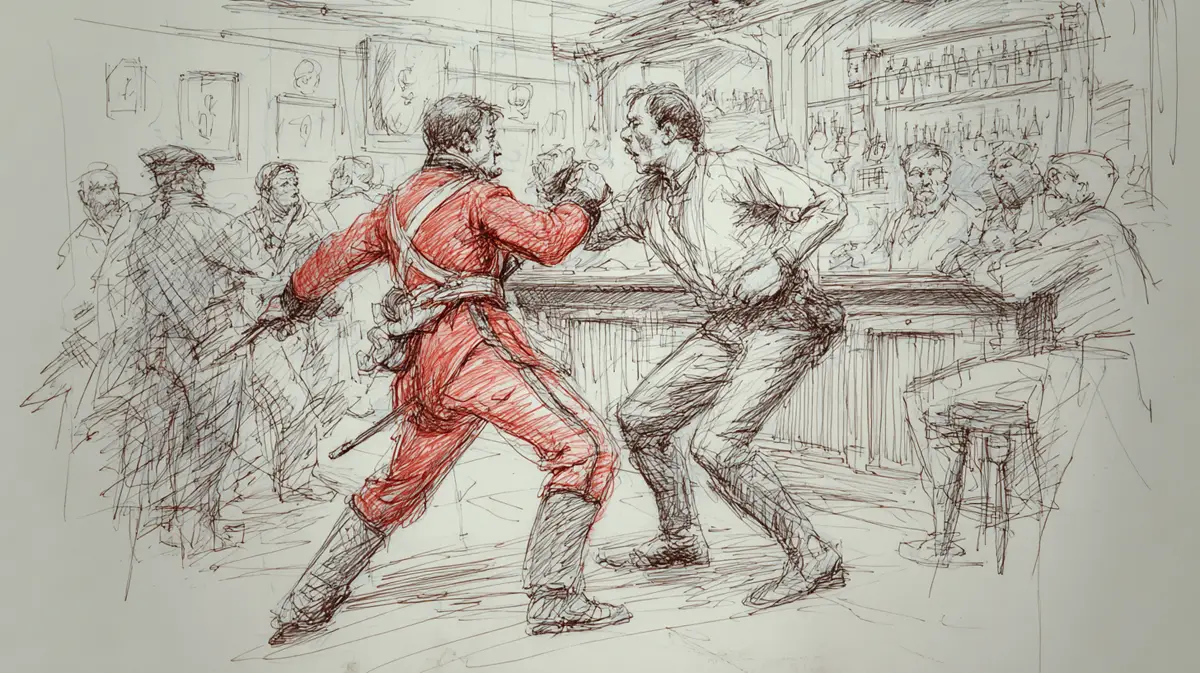

So, what caused all the trouble? It began when two officers from the Leeds Corporation Police appeared at the Green Man beer house in Kirkgate on the evening of Sunday 9 June 1844. They interviewed a man who had complained about being attacked by two officers of the 70th Foot Infantry Regiment, a military detachment garrisoned in the town. The man, a stranger to Leeds named Edward Thompson, had entered the beer house and ordered a pint of ale, laying down twopence halfpenny on the table. Before the drink was brought, one of the soldiers pocketed the money. When Thompson asked for it to be returned, the soldier – John Karin – struck him. Thompson stood up and was then struck again by another soldier, John Brian, who violently pushed him outside.

One of the soldiers then entered a nearby house of ill repute, grabbed a fire poker, returned to the street and struck Thompson on the head with such force that he was knocked senseless and sustained a serious wound.

“Serious assaults”

The constables arrested the two soldiers, but on the way to the Police Office they were attacked by more soldiers – friends of those in custody – and beaten with fists and military belt buckles. When more police arrived, a general brawl broke out between the soldiers and police. At this point, no townspeople were involved; they simply stood back and cheered the soldiers on. Karin and Brian were re-arrested, along with three other soldiers, and order was restored – but not for long.

The next morning, Monday 10 June, the soldiers appeared before the magistrates. All denied guilt except one, who remarked that only civilians were present during the assault, adding that not one of them would “sooner help a soldier than plunge a knife into him”. The magistrates found all the soldiers guilty. Sherburd and Brian, who had committed the most serious assaults, were sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. The other three were returned to their barracks and detained for twenty days.

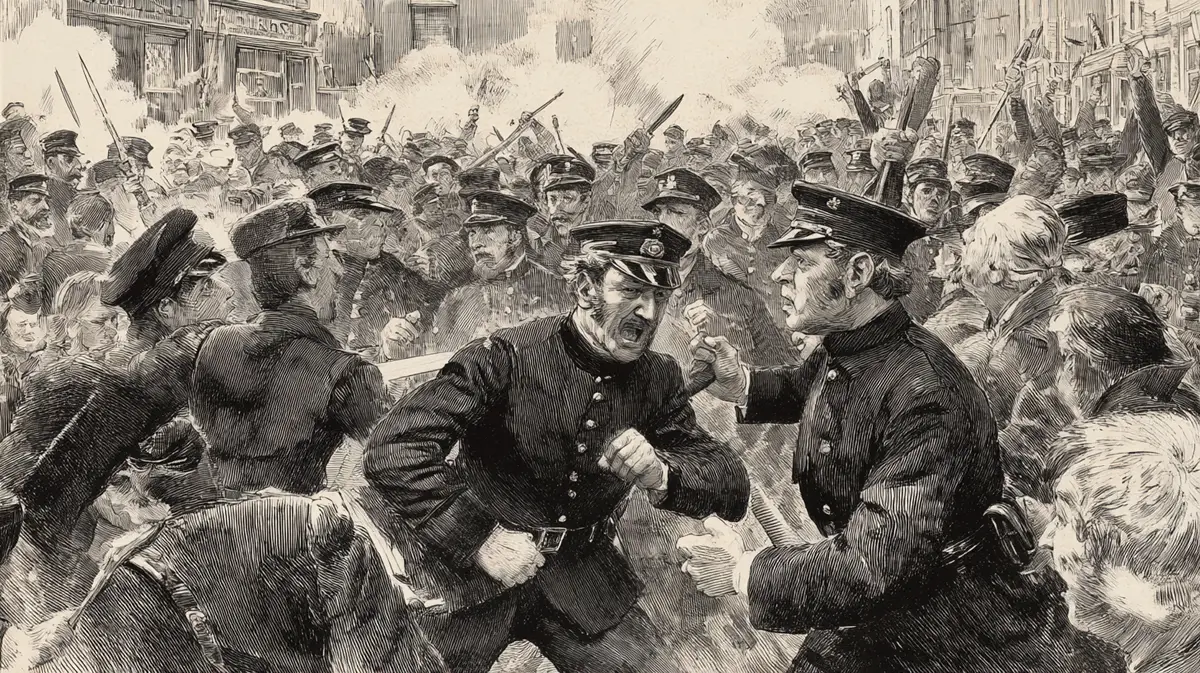

That evening, violence erupted once more. In an attempt to ease tensions, the military were confined to barracks, but orders were disobeyed. Around forty to fifty soldiers left in small groups and met at the Green Parrot Pub in Harper Street to plan revenge against the police. Leaving the pub armed with bludgeons and belts, they attacked several officers on Vicar Lane.

As the fighting moved towards Briggate, the soldiers encountered a crowd of over a thousand civilians protesting against attempts by the Leeds magistrates and police to stop Sunday political meetings. The soldiers raised the cry “Down with the Police!” and the crowd, not knowing their full intentions, joined them. In the pitched battles that followed, the police fared worst, as the townspeople actively supported the soldiers.

“Violence subsided”

A witness later reported that “the whole of the lower orders in that neighbourhood turned out in the streets and provoked the soldiers to violence upon the officers,” who were “beaten, wounded, and declared they would ‘murder all bloody policemen in the town’.” Constable Samuel Smith was the first to be attacked; he was so severely injured he had to be taken straight to the Infirmary. Constables Wildblood and Robertson also suffered serious injuries.

As the riot intensified, shopkeepers in Kirkgate, Briggate and Commercial Street were forced to close in fear of looting and damage. At the start of the disturbance, most of the night-duty police were still in bed, so no reinforcements could be sent to those already on duty. This gave the soldiers and the mob a free hand for more than half an hour, during which several more officers were injured.

Eventually, the soldiers were rounded up by their own officers and marched back to the barracks, where they were confined until the violence subsided. However, many townspeople stayed on to continue the battle.

By the time the police cleared central Leeds, four separate groups of rioters had emerged – the original Briggate crowd, one of Leeds Irish in York Street, another in Park Row, and a fourth at the barracks on Woodhouse Lane, cheering the soldiers. Several civilians were arrested, having encouraged or joined the violence.

On Tuesday 11 June, the magistrates assembled once more. The civilians arrested the night before were remanded for another day. Colonel White and two other officers of the 70th attended court. The magistrates were informed that all soldiers would remain confined to barracks. Colonel White agreed that any soldier identified as participating in the affray would be handed over the following day for full investigation.

“Defered judgement”

That evening, with the soldiers contained, a crowd of working-class townspeople – joined by Leeds Irish and Chartist radicals – pelted the police in Kirkgate with stones and bottles. This time, the police and magistrates were ready. Well-organised and armed with cutlasses, the police prevented themselves being isolated, and by 10pm, order was restored in the town centre for the first time in three days.

On Wednesday 12 June, two men arrested the night before for riot and assault were each fined £5 or given two months’ imprisonment. No soldiers appeared in court. Colonel White had promised that those involved would be identified and brought forward. Statements were taken from more than twenty witnesses, several of whom went to the barracks to identify the soldiers. Those identified were taken to court.

Lengthy legal arguments followed, but the magistrates deferred judgement until the next morning. Only two soldiers – William O’Brien and John Cosgrove – were held in custody. The others were told to return the next day.

Following further evidence, ten soldiers and seven civilians were committed for trial at the next court sessions. All the soldiers were granted bail on Colonel White’s guarantee. All but two civilians were also bailed; those without sureties were taken to prison.

At the hearing, the defendants faced 22 charges of riot and assault. All pleaded not guilty. Numerous witnesses were heard, including Constable Smith, who had only just recovered enough to testify, his head still bandaged. After giving evidence, he returned to the Infirmary.

“Premeditated”

After a three-hour deliberation, the jury returned verdicts. Soldiers Michael Coglan, William O’Brien, John Moran, Patrick McLeneghan, and John Cosgrove, and civilians Manasseh Flatlow, Daniel Davins, John Keating and Benjamin Cawood were found guilty. All others were acquitted.

Character witnesses spoke for all the guilty parties except O’Brien. The Recorder sentenced him to one year’s imprisonment. Coglan, Moran and McLeneghan received eight months each. Flatlow was fined £4 and released upon payment. Davins received eight days; Keating, seven; and Cawood was released the same day.

In his remarks, the Recorder condemned the attack on the police as “disgraceful, wicked, mean, cowardly and unsoldierlike”. Such conduct could not be tolerated in a major town like Leeds. He made a point of singling out O’Brien, whom the court considered the ringleader.

Remarkably, a confession followed. As the prisoners were being transported to the Wakefield House of Correction, O’Brien confessed to Policeman Beanland that the attack had been premeditated, planned as revenge for the earlier arrests. He stated that all soldiers involved had met at the Harper Street beer house, except Robert Harwood (acquitted), who had not participated. Coglan, though convicted, was not part of the original plot but joined in later. Other soldiers confirmed his statement.

Following the riots, the Mayor of Leeds submitted a memorial to the military authorities requesting the 70th Regiment’s removal. Although no immediate action was taken, and by late June they remained in their Woodhouse Lane barracks, the Leeds Mercury reported that marching orders were expected. A few days later, the 70th Regiment was finally – and ignominiously – marched out of Leeds.

images are representational