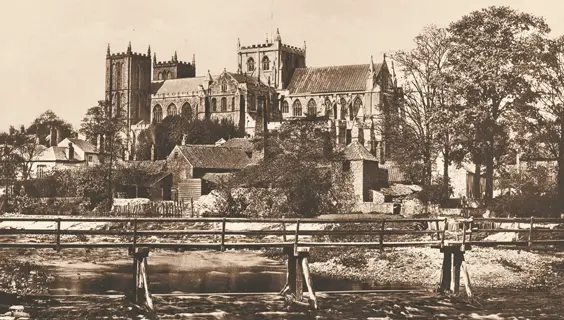

The Curiosities of Ripon Cathedral

By David Winpenny

For most of its existence, what we now call Ripon Cathedral wasn’t a cathedral. At the time of St Wilfrid, Ripon briefly had a bishop – he was Eadhead, previously bishop of Lindsey and based at ‘Sidnacester’ (probably Stow in Lincolnshire), who held the newly created Ripon see between 681 and 685.

Despite Wilfrid’s links with Ripon, he was never styled ‘Bishop of Ripon’. After Eadhead, the short-lived diocese was joined on to the see of York to form the new bishopric of Northumbria, which Wilfrid ruled for around five years before being expelled – his was a tumultuous life.

Eventually, Ripon settled down as part of the large York diocese, but it was not plain sailing for the Ripon church. Wilfrid’s monastery was sacked by the Danes in around 875, and in 937 Alfred’s grandson Athelstan fought an alliance led by the kings of Dublin, Alba and Strathclyde at the Battle of Brunanburh (possibly on the Wirral, but maybe elsewhere – historians have yet to pin down its exact location).

“Church that ran its own system of justice”

His victory, against much larger forces, is said to have been helped by his pre-conflict vow that he would give three churches – York, Beverley and Ripon – special privileges if he won. The fulfilment of this vow may have led to Ripon’s ‘Liberty’ – a wide area centred on the church that ran its own system of administration and justice, outside the king’s writ.

Ripon was also a ‘chartered sanctuary’, allowing fugitives thirty days’ safety from arrest under the protection of the church authorities. There were strict rules about sanctuary: anyone seeking it had to confess his sins, surrender his weapons and allow the church authorities to supervise his case. He then had to decide whether to surrender and stand trial or go into exile. Ripon’s sanctuary area extended to at least a mile from the church, and, where its boundary crossed the roads leading into the city, sanctuary crosses were erected.

The stump of one remains, at Sharow, just over the River Ure. Made of limestone, it probably dates from the thirteenth century and was given to the National Trust in 1900. It is the Trust’s smallest property. Another cross stood in the area of Ripon, now near the canal, known as Kangel – a corruption of ‘archangel’. In 2005 Ripon’s two rotary clubs reinstated markers – stone gateposts – on the approximate site of the seven lost crosses, and linked them with a 10-mile, circular ‘Sanctuary Walk’.

“Stopped being a monastery”

The church buildings were reduced to ruins in 984 when Ripon was burned by King Edred, another of Alfred’s grandsons. His justification for his ravaging the town – and, indeed, all of Northumbria – was, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, ‘because they had taken Eric for their king’ (that is, the Viking king Eric Haraldsson, better known as ‘Bloodaxe’).

It continues: ‘In the pursuit of plunder was that large minster at Ripon set on fire, which St Wilfrid built.’ How much of the Saxon minster, other than St Wilfrid’s crypt, was left after Edred’s depredations is unknown, but there was enough to house St Cuthbert’s body in 995. After that we know very little until after the Norman Conquest.

We do know that at some point the foundation stopped being a monastery and became a college of secular canons – ordained priests who observed the services of the church and undertook its organisation, but, unlike monks, were not bound by public vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

“Round arches of the Norman style”

By the end of the tenth century the archbishops of York regularly spent time in Ripon, with a palace on a site immediately to the north-west of the church. Whatever buildings remained may have suffered again after the Norman conquest of 1066, especially in the Harrying of the North of 1069. By then, of course, the archbishops were of Norman stock – the first of them was Thomas of Bayeux. He may have repaired or even rebuilt the Saxon church, but it wasn’t until almost a century later, under another Frenchman, Roger de Pont l’Evêque, archbishop from 1154 to 1181, that Ripon’s great minster began to assume its present shape.

If you stand inside the west end of the building, facing east, and then look up at the walls to the north and the south, you’ll see part of the nave walls built in Archbishop Roger’s campaign. This part of the building was just the width between these north and south walls – there were no aisles. The design is what’s called the Transitional style – a combination of the round arches of the Norman style and the newly adopted pointed arches of the Gothic. You must imagine this pattern repeated along the length of the nave – you can see more fragments next to the large arches that support the central tower.

Article taken from ‘Secret Ripon’ by David Winpenny, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445672168

Article taken from ‘Secret Ripon’ by David Winpenny, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445672168