Standing at the Sky’s Edge – Review – Sheffield Crucible

By Clare Jenkins, December 2022

You can’t miss Sheffield’s Park Hill flats. They snake across the hill behind the railway station, dominating the skyline. They’re also what you see from the windows of the Crucible Theatre, which is reprising its 2019 hit production of Richard Hawley and Chris Bush’s musical ode to the iconic/notorious 1960s housing estate.

These ‘streets in the sky’ were part of the city council’s postwar building boom, designed for people who’d been living in nearby back-to-backs and tenements earmarked for demolition. “It were paradise,” reflects Harry, one of the central characters, recalling carrying his bride Rose over the threshold into their brand-new marital home. “We were so grateful.’

Over time, though – like so many similar blocks of flats – cracks appeared in both the fabric and the residents. People stopped being proud of the estate as conditions deteriorated. “Junkies and prossies” rubbed shoulders with refugees, the lifts stank of urine, litter (and sometimes furniture) was thrown off the balconies. Gradually the inhabitants left or were rehoused but, instead, of being demolished, the estate was Grade II* listed in 1998, making it the largest listed building in Europe. Property developers Urban Splash took over six years later and began renovating the “man-made monolith” for a whole new hip population of academics, artists, media types and London escapees. The gentrified flats became “split-level duplexes”, the Brutalist architecture celebrated.

“Clenched fists”

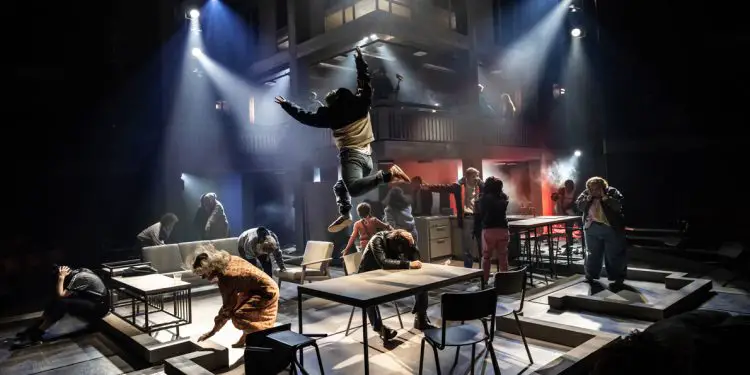

And that’s where the estate’s story currently stands, a story traced enthrallingly and empathetically over two and a half hours by Bush’s wise and witty words, Hawley’s mournfully romantic songs and a 30-strong, utterly seamless ensemble cast, including members of Sheffield People’s Theatre. Instead of taking a strictly chronological timeline, director Robert Hastie plays with time in a cleverly Priestley-esque way. Large digital clocks descend to show the years going backwards and forwards while the characters, from different decades, overlap and interweave, sharing the same unadorned grey space, even at times the same dining-table, without sensing each other’s presence.

Superb choreography by Lynne Page means that, while they and their stories ebb and flow around each other, outside on the walkways old women struggle with shopping, angry men stride home with clenched fists, young women push prams while young men carry knives, asylum-seekers keep their heads down and their eyes averted, and delivery men carry bottles of milk and boxes of groceries.

Essentially, three sets of characters, all residents of one particular flat, encapsulate the social history of the housing estate. The first occupant is steelworker Harry (Robert Lonsdale), “set to be the youngest foreman in Sheffield”. He’s thrilled with his “paradise”, telling Rose (Rachael Wooding), ”We’re sitting pretty up here, on top of the world”. They exclaim over the view, rejoice in all the mod cons and she contemplates a job on the perfume counter at Cole Brothers (another Sheffield icon, another Hawley ballad).

By the 1980s, the estate, like the city’s industries, was in decline and Harry is in Full Monty despair, embittered and emasculated by unemployment. Like another ghostly visitation, we hear Margaret Thatcher’s voice drifting out of the radio: “Where there is discord, may we bring harmony…” The Miners’ Strike looms.

“Universal messages”

The flat’s next inhabitants are refugees from the Liberian civil war, warned to keep their front door locked at all times, encountering racist taunts and threats when they venture out. “It’s not a castle, it’s a prison,” teenage Joy (Faith Omole) shouts in frustration. But she finds a friend – and eventually lover – in Jimmy (Samuel Jordan), a decent working-class white boy stumbling towards a better life which never arrives. Post-gentrification, 30-something professional Poppy (Alex Young) settles into the flat after the end of her relationship in London. “Can you get Ocado up here?” asks her bewildered mother Vivienne (Nicola Sloane).

There’s plenty of debunking of such hoity-toity Southern ways in Bush’s script: Poppy cooks slow-baked aubergine from a recipe by Ottolenghi, finds fresh turmeric in the local market, frets over gluten-free bread. There are plenty of defiantly South Yorkshire references here, too: Henderson’s Relish, the rivalry between Sheffield and Leeds, between Wednesday and United. All of which raised laughs and cheers in the first night audience. There’s even a laugh for the description of Sheffield as “this sad, grey, Brexit-voting sh*t-hole”. It will be interesting to see how such northern sensibilities travel, given that the show transfers to London’s National Theatre in February. Have they heard of Hendo’s in Highgate?

What should travel well are the universal messages emanating from this immensely human production – the meaning of Home, the importance of family, life’s hopes, dreams and disappointments, loss, loneliness and the need for love. Hanging to one side of Ben Stones’s stark split-level set is the neon-lit sign “I Love You Will U Marry Me”, the now-famous graffiti scrawled over Park Hill bridge by (the here uncredited) Jason Lowe. The story behind it – he wrote the proposal, at some personal risk, for his girlfriend Clare Middleton, but she married someone else and died six years later – is a powerfully bittersweet one of love and grief.

“Memories and wistfulness”

Richard Hawley’s melancholy ballads – ‘Tonight the Streets Are Ours’, ‘Our Darkness’, ‘My Little Treasures’ the magnificent ‘Coles Corner’ – are themselves threaded through with such emotions: “As the dawn breaks over roof slates,” runs the opening song, “hope hung on every washing line. As your heart aches over life’s fate, I know we never had much time.” Arranged by Tom Deering and directed by John Rutledge, the songs are played by a band occupying the balcony, and throb with memories and wistfulness while managing, mostly, to avoid the occasional dip into mawkishness. One particularly powerful moment is when Nikki (Maimuna Memon) appears (out of the blue) to sing ‘Open Up Your Door’ outside her ex-fiancee Poppy’s apartment. Another comes at the end of the first half, when Connie the estate agent-cum-narrator says, “The shine’s worn off, cracks are starting to show”, and the entire cast belt out ‘There’s a Storm a’Coming’ while moving frenziedly around the stage as rubbish rains down on them.

If, ultimately, the show is a tad overlong and there’s an unexpected downer towards the end, well, that can be life, can’t it? Maybe that’s what makes it all the more human, and all the more haunting.

Standing at the Sky’s Edge is at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre until 21st January

images: Johan Persson