And Then There Were None – Review – Sheffield Lyceum Theatre

By Clare Jenkins, November 2023

Back in 2015, And Then There Were None was voted the world’s favourite Agatha Christie, beating Murder on the Orient Express and The Murder of Roger Akroyd. It’s also the best-selling crime novel of all time, having sold more than 100 million copies since its publication in 1939. And that’s without an Hercule Poirot or a Miss Marple in sight.

Reading the book (formerly called Ten Little Indians), you can see why. It’s pacey, ingenious, unsettling, with a subtle but remorseless build-up of dread from the opening scenes of eight people, all strangers to each other, heading to the same house party. Written just before the outbreak of the Second World War, it’s imbued with a sense of impending doom.

Watching Lucy Bailey’s production, though, its staggering popularity is considerably less clear. Despite using Christie’s own adaptation, and despite Bailey’s enormous success with Witness for the Prosecution (now in its sixth London year), it feels one-dimensional, Cluedo-esque, ‘murder by rote’ – and often under-projected.

Like a cardboard cut-out toy theatre production, it offers curiously flat characters inhabiting a sparsely furnished, albeit chic, set. There’s a lot of standing around talking in front of a sofa (carefully avoiding the fake bearskin rug). Indeterminate music and some inconsistency in the lighting adds to the slightly threadbare effect (the right people aren’t always spotlit, the gauze curtain doesn’t always drape properly).

The play starts with the eight characters introducing themselves at the isolated, boat- and telephone-free Soldier Island just off the coast of Devon. The two servants (there to meet and greet, carry luggage, make meals, run baths – those were the days) inform them that their hosts, a Mr and Mrs U. N. Owen, won’t now be arriving until the following day. By which time, it transpires, everyone will be dead. So who’s killed them – and why?

The latter question is answered by the playing of a gramophone record on the first night, when each is accused of murder by an anonymous voice. Everyone protests their innocence but the truth is more complicated than that. And so the hunt is on for the killer before the next death occurs, the next little glass soldier disappears from the dining-table…

“Grimmer tone”

Some of the deaths occur, unconvincingly, onstage. First to go is boy-racer Anthony Marston (Oliver Clayton), in a classic Christie scene of after-dinner drinks with poisoning attached. When, one offstage death later, the elderly General Mackenzie (Jeffery Kissoon, moving from colonial authority to sorrowful guilt) appears to rise from his chair after being stabbed, knife still in chest, the response of the audience is more laughter than horror. Even more disconcerting is when the corpses rise and walk slowly off stage, glowing white like the soldiers. The final death, by contrast, seems shockingly, elaborately gratuitous.

Coronation Street’s Andrew Lancel’s ex-policeman William Blore is all oversized trousers, puppet-stiff gestures and not one but two dodgy accents (South African and Cockney).

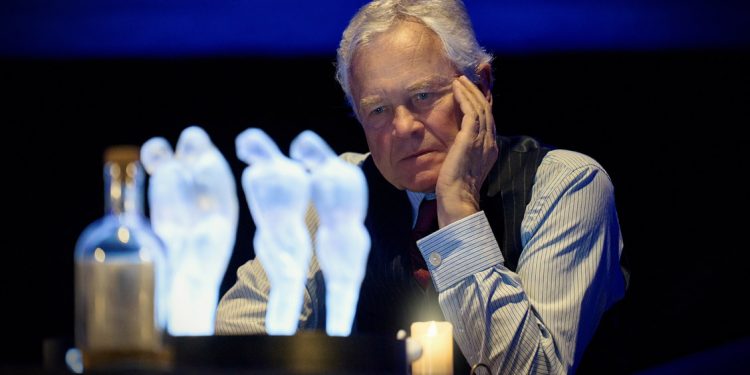

David Yelland as the assured Judge Wargrave and Bob Barrett as the increasingly anxious Dr Armstrong, meanwhile, seem to be acting in a different, more naturalistic, play. And Sophie Walter gives a strong performance as Vera, the Owens’ temporary secretary, gradually becoming more paranoid as the bodies pile up.

If the first half lacks psychological variety, Act 2 sets a grimmer tone, as the characters descend into feral Lord of the Flies fight-for-survival. By this stage, the chandelier has started to flicker, ghosts lurk behind the curtains, personalities start to unravel, perspectives start to shift. “Not all lunatics look like lunatics, eh, doctor?” as one character puts it. Slowly, the outside world begins to creep in, the stage taking on a Magritte-style surrealism, the gramophone now resting on a sandbank, sea and sky becoming indivisible.

As a result, it becomes a more interesting, more existential play about revenge and justice. But it’s still tension-lite – until the final graphic death. Which would be fine if the rest of the play built up to that – but it sadly doesn’t. And I was left wondering: isn’t this really a radio play?

‘And Then There Were None’ is at Sheffield Lyceum until Saturday 11 November. It will be at York’s Grand Opera House from 21-25 November

images: Manuel Harlan