The History of the Manchester & Leeds Railway

By Anthony Dawson

The Manchester & Leeds Railway had been envisaged as early as 1825 as one of the links in an iron chain from Liverpool to Hull, but this proposal lay dormant until 1830, when, following the triumphant opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in September 1830, a meeting was held at the Royal Hotel in Manchester on 18 October 1830, where a ‘highly respectable meeting’ took place. On 30 October 1830 the Manchester Guardian reported:

In the course of the last five years, the committee have had the opportunity of observing a gradual reform of general prosperity and a constantly increasing extension of commerce.

Capital for the railway was to come from the sale of 8,000 shares at £100 apiece. The Board was to be composed of eminent men from along the route of the proposed line. Twenty-nine Directors were appointed, at the following proportion, to reflect the ‘interests of the important places affected by the new line’:

Manchester 10

Leeds 8

Liverpool 4

Halifax 3

Bradford 2

Rochdale 2

“Progress”

George Stephenson and James Walker (who were also involved with the Leeds & Selby scheme) were appointed as joint engineers. Two routes were proposed: Walker suggested a direct route of 37 miles, which would have involved considerable civil engineering, while Stephenson’s meandering Calder Valley route was easier but 13 miles longer. One correspondent to the Leeds Mercury (on 23 October 1830) thought Walker’s route better fulfilled the aims of the Manchester & Leeds Railway by ‘the formation of the shortest, and most direct communication between Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds and Hull’.

Stephenson’s route had one major advantage over that of Walker, however, in that it proposed to connect:

Bradford, Huddersfield, Halifax, Oldham, and Rochdale &c., not merely with Manchester and Leeds, but it would be a connection of the trade of one individual place with one another…

For this reason, as well as the lower cost, Stephenson’s route was approved.

A Bill for the Manchester & Leeds Railway was presented to Parliament on 10 March 1831, where despite the fierce opposition of the canal interests, it received a first and second reading. Its progress to committee was prevented by the dissolution of Parliament on 23 April. The Board then petitioned for their Bill to be reintroduced to the next session, only for it to be thrown out at committee because ‘the preamble for an Act … to build a railway between Manchester and Leeds had not been proved’.

“Improved financial climate”

Once again the Board petitioned Parliament, but once again the Bill was thrown out, the case for the railway still not having been proved. And here the Manchester & Leeds remained for five years, until the whole parliamentary process began again in February 1836.

With an improved financial climate, no doubt thanks to the influx of slavery compensation money, and with railways such as the Liverpool & Manchester being such an obvious success, the Board of the Manchester & Leeds submitted a second Bill that, despite renewed opposition from the canal interest, received Royal Assent on 4 July 1836. The company was authorised to build its line from Oldham Road, Manchester, to a junction with the proposed North Midland Railway at the then obscure village of Normanton, 15 miles to the south-east of Leeds, which, thanks to George Hudson, would become an important early railway centre.

The Manchester & Leeds Company was formally incorporated in 1836 and Directors were appointed at a General Meeting on 8 September 1836, ‘for the purpose of proceeding in the execution of the Act’. James Wood was elected as Chairman and Daniel Broadhurst at Secretary. Directors included: Thomas Broadbent (mill owner, Huddersfield), Henry Forth, Robert Gill, Henry Houldsworth (of Manchester, future Chairman), William Hayes, Aaron Lees, John Smith, James Wood, James Simpson, Richard Barrow Jnr., and the Hon. Captain T. Best. Among the proprietors was Thomas Potter of Hyde, a wealthy Unitarian cotton mill owner who would later be Chairman of the Manchester & Birmingham Railway. Tenders for the western section were invited during June 1837 and those for the eastern section – Summit Tunnel at Littleborough being the dividing line – in May 1838.

Kirkgate station, Wakefield, as depicted by A. F. Tait in the 1840s. It is scarcely recognisable today

“Talented draughtsman”

Thomas Longridge Gooch was appointed as Resident Engineer, having cut his engineering teeth (so to speak) while working under George Stephenson on the Liverpool & Manchester. Gooch had been apprenticed to Robert Stephenson & Co. at their Forth Street Works, Newcastle, aged ‘not quite fifteen’ in 1823, and after two years in the workshops, progressed to the drawing office, where he became a talented draughtsman and surveyor. He was appointed as senior draughtsman and private secretary to Stephenson senior aged only twenty-two, with the two working side-by-side on the Liverpool & Manchester project.

Gooch prepared the first survey of the Manchester & Leeds under Stephenson in 1830, but, following the failure of the first Manchester & Leeds Bill, he worked with Stephenson Junior on the London & Birmingham line until secondment back to the Manchester & Leeds in 1835. Gooch was good company, as the civil engineer Henry Clarkson, who was in charge of the section from Todmorden to Leeds, recalled:

He was one of the pleasantest men possible to be associated with, always genial, and of a very social and friendly disposition; he was, too … of a musical turn, and used to indulge in sentimental songs … in an evening.

Railway Opposition

There was considerable opposition to the railway, not only from the canal interests, but from landowners and even towns, which were reluctant to have a railway pass through them.

Despite being shareholders and Directors of the company, the Fieldens of Todmorden were eager to extract the maximum amount of compensation from the loss of their land to the railway. The Fieldens – Joshua, John, James and Thomas – were hugely influential Unitarian mill owners and parliamentarians. They built the magnificent Unitarian Church in Todmorden in 1865, and also the town hall. For a strip of land, 300 yards long and 50 feet wide, the Fieldens claimed compensation totalling £1,819 13s 10d. According to the Manchester Courier, the court proceedings took two days:

The jury, after nearly and hour’s consultation, gave their verdict … land and buildings and timber, £1,191 10s 6d; severance, including £55 mill damages, £215.

Samuel Turner of Sowerby Bridge claimed £1,500 from the company in compensation for ‘a valuable stone quarry’ affected by the route of the line, but the company offered £500 (the value of the land). Again the dispute went to court, and the jury decided that the company should only pay Turner £475, and that Turner had to pay the costs.

A well-known postcard depicting the LYR and Great Northern joint station at Kirkgate, which was opened in 1854

“Company was in breach”

The townsfolk of Wakefield – no doubt goaded by the Aire & Calder Navigation Co. – attempted to prevent the passage of the railway close to the town in tandem with the local aristocracy, who were implacably opposed to the M&L. In May 1838 there were disputes over land in Thornes (just south of the town) and Kirkthorpe (to the east). The matter ending up in court, the jury found in favour of the railway, much to the fury of the local press.

But worse was to come, as a legal injunction was placed on the M&L Railway Company over a claim that the company was in breach of its own Act in crossing Kirkgate, a major public highway. This, remembered Henry Clarkson, was ‘one of the most important cases of litigation on this line’:

The Aire and Calder Company, who had been up to this time almost invincible, stoutly opposed the construction of the line … and actually obtained an injunction [1840] from the Court of Chancery to stop the works. The ground on which this order was granted was a clause in the Railway Company’s Act, that the said important street should be crossed by means of a viaduct. The Aire and Calder Company contended that this implied an opening over the entire width of the street; the Railway Company … insisted on their right to build two piers in the street forming one large opening for carriages, and a smaller one on each side for foot-passengers. The case went before Judges in London, who sent it down to be tried at York before a special Jury.

Matters became so heated that some of the infuriated townsfolk expected the company to demolish the viaduct. The York jury found in favour of the M&L, but the Aire & Calder Company had been so sure of their success in court that ‘a sumptuous dinner had been ordered in anticipation of their victory’, which was eventually eaten by the M&L party, who ‘enjoy[ed] the good things provided for [their] opponents’!

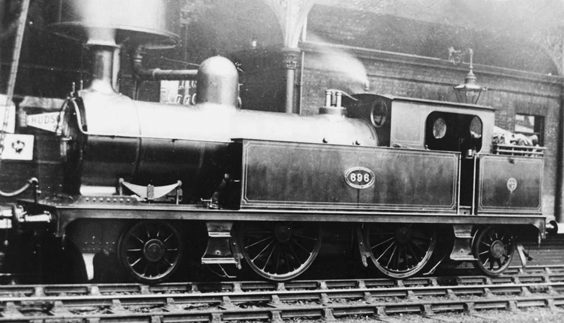

Photographed at Kirkgate in 1908 is one of Aspinall’s 2-4-2 radial tanks. No. 696 was built at Horwich in August 1898, being scrapped forty-nine years later by the LMS, in 1947

“Magnificent stone building”

While under construction, part of the Kirkgate viaduct collapsed, killing one of the workers, James Williams. Henry Clarkson remembered:

On the 8th November 1838, I was walking to Wakefield from Sandal with my Clerk, William Paley, and had almost reached the recently formed viaduct across the Ings Road, at the moment that a heavy train of loaded wagons, drawn by horses, was passing over it. Just before we reached it, I saw the sides of the arch suddenly give way; the centre rise up, and then fall in a confused mass … The man in charge of the wagons and the horses was killed and the Inspector of the works had a very narrow escape, being only saved by my shouting loudly to him…

Undaunted by this tragedy, or the legal case, the company pushed on with rebuilding the viaduct, much to the disgust of the Tory, Anglican Wakefield Journal:

Workmen are completing the viaduct over Kirkgate … we presume that some arrangement has been entered into between the contending parties … We have understood that the case was not to have been settled…

The station at Wakefield was built at Kirkgate, on a plot formerly occupied by strawberry fields and Joseph Aspdin’s cement works, where he produced his patent ‘Portland Cement’. It was opened on 5 October 1840. In the station approach was built the Wakefield Arms Hotel – using Aspdin’s cement – to provide passengers on the M&L at Wakefield with refreshment, meals, beds and ‘good stabling’. The original timber station was replaced by a magnificent stone building in 1854, built as a joint station by the Lancashire & Yorkshire and the Great Northern. After many years of neglect, Wakefield Kirkgate was restored from 2013 to 2015 at a cost of £4 million to breathe new life into the building, which had been unmanned, unsafe and virtually derelict since the 1970s (despite being the larger of Wakefield’s two stations).

The site of the contentious M&L bridge over Kirkgate, Wakefield. The current structure was built by the LYR when the line was widened at the turn of the century

“Unsuitable to transport bulky cargoes of wool”

Between November 1839 and March 1840 there was a court injunction halting the railway works at Healey Mills, about a mile west of Horbury. The M&L Act empowered it to divert the Calder but not to interfere with the supply of water to nearby business, including the scribbling mill at Healey New Mill (now a Grade II listed building). Benjamin Hallas, owner of New Mill, claimed that the diversion of the Calder had left ‘the … mill entirely dry’, and furthermore the access road had been diverted and reduced in width (from 15 feet to 11), so that it was now unsuitable to transport bulky cargos of wool to and from the mill. Finally, a decision was reached in favour of the M&L in early March 1840, when the Lord Chancellor dissolved the injunction.

The Aire & Calder Company’s opposition to the M&L kept their respective lawyers busy for years. The M&L announced it was to cross the Calder at Broad Reach, where the Calder meanders considerably, and under its Act the M&L had powers to divert the river. The M&L announced in January 1839 that it was to divert the route of the river ‘near to Kirkthorpe, in the parishes of Warmfield and Wakefield’. It was initially planned to cross the Calder by three bridges, but to reduce the cost of building the railway a single three-arch skew bridge and embankment were proposed instead. This change of plan required the re-routing of the Calder, which was blocked by several wealthy Wakefield landowners, claiming that the plans for this work had not been submitted to the Navigation Company for perusal. As a result, the court had a stop placed on the work yet again.

An East Midland Trains Class 43 rushes along the M&L bridge over the Calder at Broad Reach, summer 2017

“Interfere with boats”

The railway company eventually paid some £12,352 to the canal interests to enable the diversion of the Calder at Broad Reach and to enable their work to continue. Despite this, however, when the company erected a temporary bridge crossing the Calder in March 1840, the Aire & Calder people fought back, claiming it would interfere with boats plying the river. The diversion of the Calder required the excavation of a ‘new cut’, which considerably straightened and shortened the river at this point, and as a result should have been favoured by the canal interests.

Despite all the expensive legal ramifications, the ‘new cut’ was ultimately of little use, as the Aire & Calder Navigation had opened its own cut between Broad Reach and Stanley Ferry, effectively bypassing the one dug by the railway. This new cut was opened on 15 March 1839 and involved the construction of an iron aqueduct at Stanley Ferry (described as ‘perhaps England’s least well-known canal structure of any significance’), which was built under the Aire & Calder Co.’s Act of 1828. The first boat to cross the new aqueduct was the schooner James, which had been built in Wakefield.

Article taken from ‘The Early Railways of Leeds’ by Anthony Dawson, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445667805

Article taken from ‘The Early Railways of Leeds’ by Anthony Dawson, published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99 paperback, ISBN: 9781445667805