The Romans in Yorkshire – A Concise History

By Ingrid Barton

Julius Caesar invaded Britain in 55 BC but the Romans did nothing more until 43 AD when the Emperor Claudius, ostensibly at the request of a British king, landed near what is now Colchester and began a conquest of the land. Soon Roman armies had advanced as far north as the river Don and the silence of prehistory is broken as, for the first time, individual people in our region are mentioned by Roman historians.

Immediately we are in the middle of a story. It concerns that dominating northern tribe, the Brigantes. Its reigning queen, Cartimandua and her consort, Venutius, are not getting on too well – keep an eye on the handsome armour-bearer! It seems she has decided that these new invaders are powerful enough to make good allies and has agreed a peace treaty with them (whether, as the Romans said, she has also agreed to give them sovereignty over her tribe will never be known – there are no Brigantian historians).

One day, to ingratiate herself still further with the Romans, Cartimandua sends back to them, in chains, Caractacus, a rebellious British prince of the Catuvellauni tribe who had come to her court seeking asylum. Venutius has been unhappy for some time about the cosy deal with the Romans, but treating a suppliant and guest in this way is going too far. The relationship with his wife completely breaks down. She abruptly divorces him and installs the armour-bearer in his place. He raises an army and attacks: she calls on her new allies for help. The Romans are delighted: now they have a perfect excuse to send troops north of the Don.

The ‘Venus Mosaic’ comes from the floor of a Roman villa discovered in Rudston, East Yorkshire in 1933

“Extensive occupation”

The leader responsible for the pacification of what was later to became Yorkshire is Quintus Petilius Cerealis, the Roman governor of Britain who, ten years before Cartimandua asked for help, had helped to defeat Queen Boudicca. He now leads the Ninth Legion from its base at Lincoln, crosses the Humber, probably at Petuaria (Brough) and, at about two days further march north, establishes a fort on a well-positioned site between two rivers. It is given the name Eboracum (now York). Cartimandua is restored to power, but it is only a matter of time before further revolts lead to more extensive occupation and eventually to the total conquest of Brigantia; York, in time, becomes the capitol of Northern Britain. Cartumandua’s story, unlike Boudicca’s, remains without an ending.

The strategic siting of York had lasting effects on the subsequent history of Yorkshire, as it became the pivotal point of the all-important northern road system when the conquest moved up country. From here, for centuries, expeditions against troublesome northern tribes were organised. York connected Ermine Street, coming up from the South, with the most important forts: Calcaria (Tadcaster), Isurium Brigantium (Aldborough), Calaractonium (Catterick) and, in time, all the marching camps and forts established in the Pennines right up to Hadrian’s Wall. Roads from York also went east, to Bridlington on the coast, and to Delgovicia (probably Malton).

Roman wall and the west corner tower of the fort at York, with medieval additions

Kaly99 at the English Wikipedia [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

“Freedom from taxes”

Eboracum itself became one of the biggest military centres in Europe. Its impressive fort walls stretched along the river Ouse, strengthened with multi-angular towers, one of which can still be seen. Behind this, where the Minster now stands, was the pillar-lined main administration building. (One of its pillars, erected upside down, stands outside the South door of the Minster.) Stonegate and Petergate are on the line of the original fort’s thoroughfares.

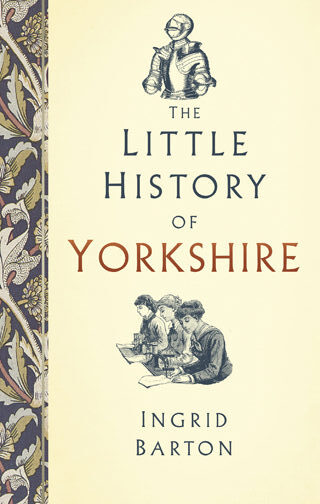

York’s military importance meant that no less than two Roman emperors were in Eboracum when they died. The first was Septimius Severus in 211. His sons, Caracalla and Geta, were declared co-emperors (Caracalla murdered Geta not long afterwards). The second was Constantius Chlorus whose son, Constantine, was hailed emperor by the army in 306. He went on to Christianise the empire and move its centre from Rome to Constantinople.

Although never really officially approved, it was very common for a civilian town or vicus to grow up next to a Roman fort. The one at York was located on the west side of the Ouse, where the cemetery and, probably, the yet-to-be-discovered amphitheatre were also situated. (The beheaded skeletons of gladiators were discovered nearby in 2004.)

Eboracum’s vicus was declared to be a ‘colonia’ by the emperor Caracalla. This term was used for a settlement of veterans and once carried with it certain benefits including freedom from taxes, but we don’t know if that was the case with York.

Emperor Septimius Severus; Marble from Altes Museum, Berlin

[GFDL or CC BY 3.0], from Wikimedia Commons

“No evidence of violence”

Isurium Brigantium (Aldborough near Boroughbridge), although only a small village today, was the second largest military settlement in the area. The road that runs next to it (mostly on the line of the A1) connected Eboracum with forts right up to the Antonine Wall, while another road branched off from it to Luguvalium (Carlisle). The church stands on what was the forum of the town. Its amphitheatre, the largest in northern England but lost for centuries, was located in 2011 at nearby Studforth Hill, thanks to the help of geomagnetic scanners, but it has yet to be excavated. The fort itself is in the care of English Heritage.

But what of that other Yorkshire tribe, the cart-driving Parisi? It seems that they were friendly with the Romans from the beginning and so their immediate fate was rather different to that of the Brigantes. It is likely that their territory provided safe passage for Roman troops during the first phases of the conquest of the Brigantes (who were tribal rivals). If so, the Romans were suitably grateful, for there is no evidence of any violence in the capitol, Petuaria (Brough) and the area seems to have gone its own way and prospered quietly as the Parisi too came under Roman rule.

Life for ordinary farming people in Roman Yorkshire was far less influenced by the occupation than further south, where large slave-run farms provided huge amounts of grain for the army. Field systems remained much the same as before and the traditional round houses, some of them hundreds of years old, remained in use. A few villas were built, notably those at Rudston and Langton, but there is curiously little evidence that typical Roman goods like glass, kitchen ware and amphorae of wine found their way down to ordinary people. Even the mosaic floors that survive are merely crude country versions of the more splendid ones in southern villas.

“Modest prosperity”

There was a fort at Hayton, a day’s march from Eboracum at the foot of the Wolds, and extensive excavation nearby has revealed the remains of bath houses, a timber-lined well and stone-built buildings, as well as a number of more traditional round houses. A little further down the road at Shiptonthorpe there was another ribbon development, of wooden houses this time, probably belonging to retired soldiers. Roman export items were found in all the places associated with the fort, whereas nearby Holme-upon-Spalding-Moor, where there were industries such as potteries, had almost nothing in the way of luxury goods.

The main point of conquest (apart from providing career opportunities for aspiring young Roman commanders) was to obtain resources and taxes. In Yorkshire there was lead, coal and ironstone to be exploited and good clay to be turned into saleable pots. There were potteries at Crambeck, Knapton and Norton as well as Holme-upon-Spalding-Moor, leather tanneries at Catterick, and iron foundries in many places. Ordinary folk, no doubt, bought some of these products but they were mostly sold to the military, along with food supplies, bringing modest prosperity to the region. The security provided by the army maintained peace during years that in much of Europe were very turbulent.

“Began recalling its soldiers”

“Began recalling its soldiers”

This peace deteriorated during the fifth century when Anglo-Saxon raiders from Germany began to attack the coast. For many years they were successfully turned back by the army, which built defensive coastal forts at Scarborough, Filey, Flamborough, Goldsborough, Huntcliff and Ravenscar. However, Rome itself was in trouble, coming under increasing attack from the Goths, and riven with internal dissentions. It began recalling its soldiers from the outskirts of the empire. In 410 the last of the Roman army left Britain. Its inhabitants, used to someone else defending them, were now left alone to face the invaders.

Yorkshire Folk: From the tombstone in York of Corellia Optata, 13 years old, possibly from the vicus:

‘To the spirits of the departed. Ye hidden spirits, that dwell in Pluto’s Acherusian realms, whom the scanty ash and the shade, the body’s image, seek after life’s little day, I, the pitiable father of an innocent daughter, caught by cheating hope, lament her final end. Quintus Corellius Fortis, the father, had this made.’

Places to Visit:

Wheeldale Roman Road, near Goathland

Aldborough Roman Site, Boroughbridge, North Yorkshire

The Yorkshire Museum, Museum Gardens, York

Cawthorne Roman Camp near Pickering, North York Moors

‘The Little History of Yorkshire’ by Ingrid Barton is published by The History Press, £12 hardback,

ISBN: 9780750983563