The History of Ilkley Spa

Ilkley is well-known as a ‘spa town’ – and, as author Melanie King explains in this extract taken from her new book, there was a time when people would come from miles around to experience the ‘water cure’…

About the same time Wilson and Gully set up hydrotherapy centres in Malvern, another convert from the Gräfenberg hydrotherapy centre in Silesia decided to do something similar in Ilkley, West Yorkshire. The former mayor of Leeds, Hamer Stansfield, persuaded friends to create a consortium to build the Wharfedale Hydropathic Establishment and Ben Rhydding Hotel.

Ilkley already had cold-water baths – three of them, in fact. Ilkley had an ancient well reputedly good for treating scrofulous cases when the water was either drunk or bathed in. In 1760 the local landowners, the Middeltons, constructed three baths, the establishment ultimately known as White Wells, high above the town – cold-water plunge baths that, high on the moor, were not for the fainthearted. A roof was not added until the 1820s and merely setting out on Ilkla Moor baht ’at (without a hat) – as the Yorkshire song reminds us – could make a person ‘catch thy deeath o’ cowd’. Reaching White Wells was not an endeavour for the frail and infirm in any weather, even (as people often did) on a donkey following the craggy, winding path. Stansfield could see the advantages of the pure, cold waters but realised that to become successful his establishment needed to be more accessible.

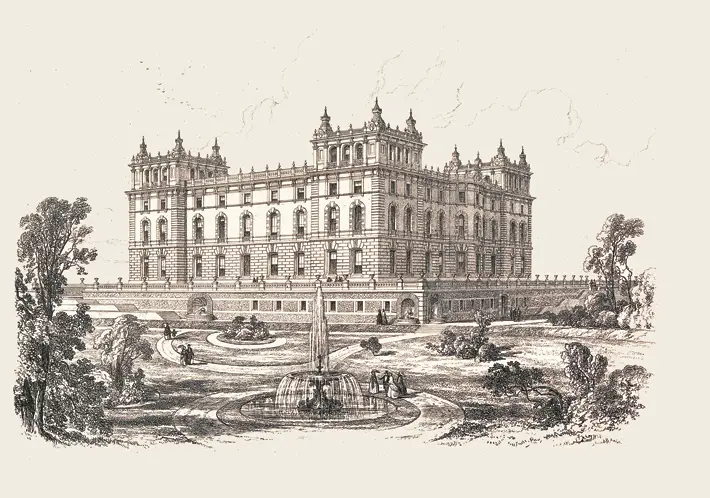

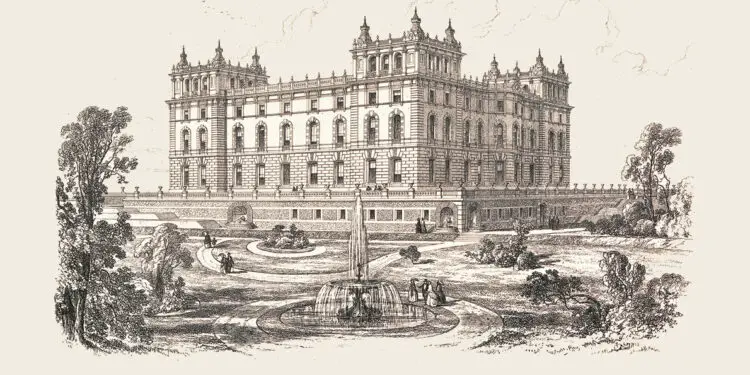

Ben Rhydding Hydro was therefore built on Otley in Wharfedale, on the edge of Ilkley Moor. Stansfield designed the house with turrets, giving it the appearance of a grandiose castle. Rooms were luxurious, with private bathrooms and entertainments that included a bowling alley. When its doors opened in 1844, treatment followed a similar format to those in Gräfenberg and Malvern: wet sheets, cold showers, bracing hill walks, and a plain diet with the added bonus of hearing the Scriptures read aloud each day after breakfast.

Ben Rhydding Hydro was therefore built on Otley in Wharfedale, on the edge of Ilkley Moor. Stansfield designed the house with turrets, giving it the appearance of a grandiose castle. Rooms were luxurious, with private bathrooms and entertainments that included a bowling alley. When its doors opened in 1844, treatment followed a similar format to those in Gräfenberg and Malvern: wet sheets, cold showers, bracing hill walks, and a plain diet with the added bonus of hearing the Scriptures read aloud each day after breakfast.

“Men and women allotted separate days”

In 1847 Dr William Macleod, after spending time in Malvern with Wilson and Gully, became manager of the Ben Rhydding Hydro. Macleod saw a tempting business opportunity and soon bought all the shares, at which point he began making substantial changes, including adding a Turkish bath and creating three separate baths based on his interpretation of an Ancient Roman bath. The first room he called the frigidarium, an open-topped room with couches and dressing rooms to prepare clients for their Turkish bath and then for relaxation afterwards. The next room, the tepidarium, was a smaller room with steamy temperatures of 90–110°F, followed by the hottest bath, the calidarium, where temperatures reached 140–150°F. Macleod decided against incorporating the rough Turkish massage, introducing instead a gentler version on shampooing tables (‘shampoo’ comes from the Hindustani word for kneading, pressing or massaging). Cold-water baths were naturally provided, as well as douches, with men and women allotted separate days for their treatments. Unlike in Malvern, under Macleod’s management at the Ben Rhydding plenty of fine food and alcohol was available.

The beauty of Ilkley and the Victorian enthusiasm for the water cure soon attracted other entrepreneurs to the area. In 1856 Benjamin Briggs Popplewell and a group of Bradford businessmen bought land on the southern slopes of Ilkley Moor to build the Wells House Hydro. It was initially run by a German, a Dr Antoin Rischanek, but his ‘foreign ways’ proved unpopular in Yorkshire, and before long he was replaced by a Sheffield doctor. Within a few years, another establishment opened nearby, Craiglands, whose name referred to Craig Tor on the adjoining moor. Various other establishments likewise opened in the second half of the century, such as Rockwood House, Marlborough House and Moorlands. All offered the comforts of a high-class vacation with the damp sheets of the water cure.

The increased competition, both in Ilkley and from elsewhere, caused a drop in patient numbers at Ben Rhydding. The addition of a golf course in 1890 failed to attract more patients, but when golf ultimately proved more popular than hydrotherapy the spa became the Ben Rhydding Golf Hotel. During the Second World War the hotel was recommissioned for the Wool Control Board and in 1955, having never reopened as a hotel, the building was demolished.

The Ben Rhydding Hydro was responsible for spawning a similar treatment centre in Matlock, Derbyshire. In 1846 a wealthy 43-year-old cotton-mill owner named John Smedley contracted a chill and a fever while on honeymoon in Switzerland. Years of treatment with drugs proved ineffective (one alarming manifestation of his illness was a religious mania). Then in 1849 he spent time wrapped in damp sheets in Ilkley. Smedley was so impressed with the water cure that he dedicated the rest of his life to establishing a hydrotherapy hospital for his employees at Lea Mills. Since he recognized that many working people could not afford the fees most hydrotherapy centres charged for a month’s treatment, Smedley had patients from his mill treated at his house, which he turned into a free hospital. The Smedley Hydro had its origins in the small dwelling that he purchased on the Matlock Bank in order to house six patients, who paid 6 shillings per day. It opened in 1853, and Smedley continued to treat patients for free in his home. Recognizing that not all patients, especially the frail, could withstand the harsh regime and frigid waters applied in Gräfenberg, Malvern and Ilkley, Smedley adjusted the temperature of the waters to spare the most delicate frames. He also treated his patients with mustard packs – an innovation the purists saw as a departure from the water cure, and one that, moreover, had been introduced by a layman, they argued, rather than a physician. ‘Yes,’ wrote one of his defenders, ‘because John Smedley had not got a series of letters tailing off after his name he was a quack. Anyway he quacked to good purpose, and sent his patients away quacking with joy over their restored good health!’

“Fashionable watering hole”

Matlock, in a gorge alongside the River Derwent, had been developed as a spa in the early decades of the eighteenth century, complete with baths, hotels and an assembly room. It was in the latter establishment in 1804 that the bashful young Lord Byron, a Harrow schoolboy unable to dance because of his club foot, watched in envy as his cousin Mary Chaworth was led onto the floor. By that time Matlock had become a fashionable watering hole. Smedley’s was not the first hydro in the area; three others had opened in previous years, including the one in Darley Dale, 2 miles distant, opened by Dr Rischanek in 1848 following his departure from Ben Rhydding. His house featured fourteen bedrooms, a beautiful dining room, pleasure gardens, baths, douches and accommodation for twenty patients. However, Smedley’s Hydro became the most well known in Derbyshire, in part due to its owner’s forceful personality and missionary zeal. God played an essential role in his personal life as well as in the water treatments. In 1850, having fallen out with the Church of England and converted to Free Methodism, he built a number of schools and chapels around Matlock, earning the nickname the ‘Prophet of the Peaks’ – a moniker that owed as much to his faith in water as to his faith in God.

Daily routine at Smedley’s establishment was regimented, disciplined and frugal. He claimed that his system of treatment was mild, ‘with the application of bandages, not used in the same way elsewhere, and some newly invented baths’. Meals were simple, while books, newspapers, tobacco and alcohol were banned. Visitors were banned on Sundays. The establishment had a monastic element, complete with periodic silences and readings from the Scriptures. Fines were levied on anyone who broke the rules. The effectiveness of his treatments meant patient numbers steadily increased. In 1860, 110 patients visited Smedley’s, with numbers three years later climbing to 1,050, plus more than 400 more treated at his free hospital. By 1867, some 2,000 patients visited each institution. So many new patients wished to attend that in 1868 Smedley was obliged to add a new four-storey wing.

Smedley died in 1874, but not without having groomed a successor, a young doctor named William Bell Hunter. A limited company purchased the Hydro and improvements were made to the house. Dr Bell Hunter remained in post until his death in 1894. Smedley’s wife Caroline Ann lived for more than twenty years after her husband’s death, opening the Smedley Memorial Hydropathic Hospital on Bank Road in 1882 as a memorial to her husband. This was not part of the new Smedley company and relied on subscribers to continue its role as a hospital for the poor.

In 1891 Kelly’s Derbyshire Trades Directory listed more than twenty hydropathic centres in Matlock. By that time, however, the water cure had spread far beyond Malvern, Ilkley and Matlock, having reached all parts of the United Kingdom. As early as the 1860s more than twenty new treatment centres had appeared in established spa towns as original bathhouses were converted for hydrotherapy or else purpose-built facilities were attached to hotels. Hospitals that offered free spa treatments to the poor – the Bath Mineral Hospital, the Devonshire Royal Hospital in Buxton and Margate’s Royal Sea Bathing Hospital – all added the latest hydropathic services and equipment to their treatments.

‘The Secret History of English Spas’ by Melanie King, £25, Bodleian Library Publishing

Published on: 7 September 2021

ChatGPT said:

html

Copy

Edit