Masbro Boat Disaster, Rotherham

By Vivien Teasdale

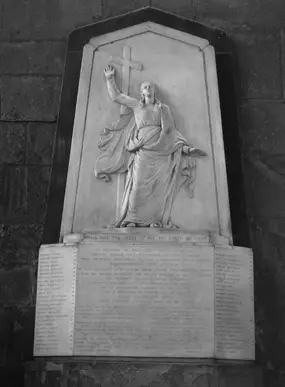

Walk around Rotherham Minster Church (previously Parish Church of All Saints) and it will not be long before you see a beautifully carved marble memorial with a long list of fifty names. Look closer and you will see that only three of those remembered there were adults.

This was not the result of some industrial disaster involving child labour, but a day of celebration that quickly turned to tragedy. Boat builders Chambers and Son of Masbro’ (Masbrough) had been commissioned to build a new boat at their boatyard on Forge Lane, for Henry Cadman of Sheffield and Robert Marsh of Doncaster.

By 14 July 1841 the John & William was ready to be launched into the River Don where the river is so narrow that boats had to be launched sideways: a traditional method which had never caused any problems before. However, the John & William was slightly different. It was of a type known as a ‘billy boy’ – a flat-bottomed coastal vessel, mainly used on the east coast. But they were usually only 5 feet 6 inches in height from the keel to the deck but this one was 7 feet high. This shouldn’t have made such a lot of difference but it may have made the boat less stable.

“Sudden increase in weight”

Another tradition in the area was to fill the boat with people, especially children, who particularly enjoyed the excitement of the day, the flags flying, the gathering speed of the boat sliding down the slipway and the massive splash as it hit the water. Families and neighbours gathered on the banks to watch the spectacle as the boat filled with boys, many playing truant from the nearby school. There were superstitions too. No members of the owner’s family were allowed on board and no women; they would bring bad luck to the launch.

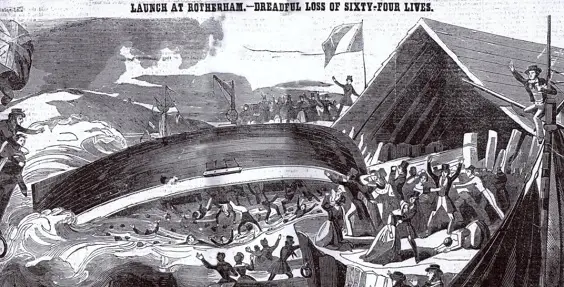

A glorious morning set the scene for the long awaited launch. As soon as the boat was full of cheering, eager children the signal was given and the supports at each end of the boat were struck away. One end freed immediately and the boat began to move, but the other end stuck. On deck, the boys ran to see what was happening and the sudden increase in weight on one side of the boat caused it to keel over and submerge into the river. ‘Their joy was transformed into despair and a thrill of horror prevailed all around’ an eyewitness wrote to the Rotherham Advertiser in later years.

Some were fortunate. They were thrown from the boat as it turned over and landed close to the opposite bank, where willing hands dragged them ashore. As always, the courageous appeared. George Langthorne leapt into the icy water to rescue some of the boys and John Johnson of Doncaster Gate was seen to dive down three times and each time bring two of the boys to safety. William Freeman also dived, desperately searching for his sons: Samuel, aged sixteen, and little William junior, who was only eight.

“A builder climbed onto the keel”

Their father saved at least five boys, but both his own lads perished. Another family who suffered more than one loss was that of John Smith, a waterman who had taken his two sons, Charles and Henry, to the event. All were lost, leaving his widow, Ann with their small daughter, Miranda, who was only one year old. Henry Newsome, a carpenter, was luckier. He jumped in and managed to save his son, Henry junior, who was only nine. His daughter, Ann, who worked as a nurse for the Hague family had an equally lucky escape. She had taken John Hague to see the launch but had been ‘seized with a presentiment of danger’ and left the ship before the launch.

Then matters became even worse. The owner, Mr Chambers, desperately hoping to help, shouted that the people must be saved and to sacrifice the boat if need be. Captain George Taylor of the John & Joseph and a builder who was nearby climbed onto the keel and tried to axe a hole through to the trapped victims but air getting into the boat simply made it sink deeper. Many blamed this single action for the greater loss of life.

Everyone rallied round. With a typical Victorian approach, brandy to refresh the survivors was sent by Joshua Crosland of the Waggon & Horses, William Flockton of the Hammer & Vice and Mrs Horsfield of the Ship Inn. The Quarter Session court,which was being held nearby, had to be halted as people flocked to the area and the police were needed to hold back the crowds, some just trying to get a glimpse of the action, others crying desperately for their children.

“Bells were muffled and tolled for three days”

About half of the boys who died went to the British School, which was nearby. One lad was heard to say that: ‘Mr Sharp, our worthy schoolteacher, did not give us a holiday or make any reference [to the launch] so half the school played truant and went to the launch.’ Rotherham also had a charity school known as the Feoffee’s School, providing education for poor boys.

The master of the school, John Mycock, who lived nearby at the Crofts, was quick to write to the newspaper refuting the suggestion that some of his boys had been killed, since ‘not one Charity boy was present upon the sad occasion’. No doubt the trustees would have asked questions if those receiving charity had absented themselves for such a frivolous reason. There were some positive events though. John Bletcher, aged fourteen years, was pulled out unconscious but awoke later in his home in Roger Lane, Hollowgate.

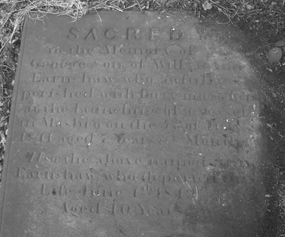

Many of the dead were buried at the parish church where the bells were muffled and tolled for three days. Others were buried at the Independent chapel in Masbrough on College Road. This is now a warehouse and few of the gravestones can be seen. Most are in appalling condition. Only one gravestone referring to this event is still legible – that of George Earnshaw, whose mother, Ann, died the year after her son:

‘Sacred to the memory of George son of William and Ann Earnshaw who awfully perished with forty-nine others at the launching of a vessel in Masbro’on the 5th July 1841 aged 7 years and [8?] months. Also the above named Ann Earnshaw who departed this life June 4th 1842 aged 40 years.’

“Verdict of ‘accidental death’ on those who died”

Subscriptions were called for to help the families and in the days following the disaster the newspapers listed all those who gave a donation. The managing committee included: Thomas Badger,who was also the coroner overseeing the inquests, Andrew Crawshaw, (treasurer) watchmaker and jeweller; William Beatson, chemist; John Aldred, chemist; Rev James Bromley; William Earnshaw; Benjamin Badger, auctioneer; G W Chambers;Thomas Law, linen and woollen draper; William Bingley; George Taylor; Frederick Fleck, iron merchant; George Hutchinson; Francis Parker; William Wingfield; C S R Sandford, fire iron manufacturer (of Sandford & Yates); Alexander Grant; George Knowles; John Graves Clark; Richard Haggard; John Barras. All these men also served on the inquest jury except George Knowles, Richard Haggard and John Barras.

The inquest, held at the Angelpub in High Street, eventually brought in a verdict of ‘accidental death’ on those who died, but the boat owners also had to pay a ‘deodand’ of one shilling. A deodand is a forfeit to the Crown, usually given to charity, when an animal or object, in this case the boat, has caused a death. Not surprisingly at a later meeting of the local council it was recommended that in future shipyards should ensure ‘the entire exclusion of all unnecessary persons, but especially children, from their vessels at the time of a launch’.

Article taken from ‘Yorkshire Disasters: A Social and Family History’ by Vivien Teasdale, £10.99 from Pen & Sword

Top image taken from a local press clipping, Rotherham library