Ancient India, Living Traditions Exhibition, British Museum, London – Review

By Clare Jenkins, May 2025

At both the start and the end of the British Museum’s latest exhibition, there are stone, marble and golden statues representing three of the main Indian religions: a pot-bellied, elephant-headed figure engaged in a playful jig, a serenely seated Buddha, and another meditator, cross-legged and closed-eyed, a sacred ‘endless knot’ emerging from his chest.

The first is Ganesha, one of Hinduism’s best-loved gods. The second is indeed the Buddha. And the third represents one of the 24 enlightened teachers (tirthankaras) of Jainism, the religion that holds all life so sacred that devotees use fly-whisks and face masks to ensure they don’t harm even the smallest of insects.

The statues set up the theme of the exhibition: how, between 200BC and 600AD, each faith represented its beliefs and deities in art. How each one interpreted the divine in an increasingly earthly way that believers could relate to. How, therefore, over the course of 800 years, those sacred images moved from abstract representations to human and animal form.

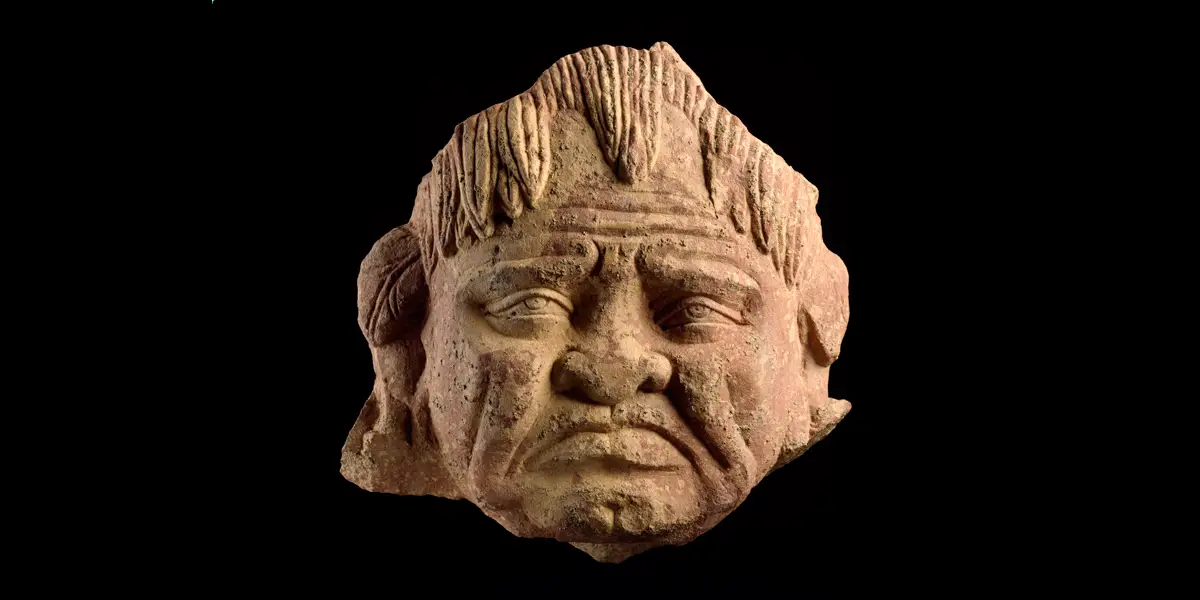

Head of a grimacing yaksha, about 2nd or 3rd century.

This mottled pink sandstone figure represents a yaksha (male nature spirit). Yakshas can grant prosperity but also make life difficult if not properly placated This is represented by the fierce or scowling expressions on these yakshas. Leaves sprout above this yaksha’s ears which possibly connects him with trees.

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

“Atmospherically staged”

Here, for instance, is a terracotta teeth-baring yaksha – a male nature spirit, looking not unlike the kind of gurning carved head you can find in York Minster’s Chapter House. Over there is the female version, the yakshi, looking considerably more sensual with her curving, bejewelled figure and ample breasts. Small terracotta figures of both have been found across the subcontinent – just as you might find images of divinities in many religious households today.

The Buddha, meanwhile, is initially represented simply by footprints – including tiny ones on a swaddling blanket held by an attendant nurse straight after his birth, as depicted on an intricately carved relief taken from a Buddhist stupa in Amaravati, south-east India. It took a few more years before he started to appear in familiar physical form, seated in the lotus position, with elongated ears, half-closed eyes, and the oval shape on his head indicating his eventual enlightenment.

There is much to linger over in this atmospherically staged exhibition, with its wafting silk drapes, soothing lighting, and soundtrack of birdsong, temple bells, and music played on the tabla and sitar. Each religion is given its own space – which could lead to the argument that too much is crammed in and the historical and religious scope is too wide. But it’s still a pleasure to explore.

Silk watercolour painting of the Buddha, China, about AD 701–750.

From about the third century BC, following trading networks, Buddhist missionaries took their faith and its devotional art beyond India. In different regions, Buddhist art merged with local ideas and art to form new artistic styles. This is one of the oldest and best-preserved paintings from Cave 17 – the famous ‘Library Cave’ at Dunhuang. It shows the Buddha, seated between bodhisattvas, with his hands in the gesture of preaching. This composition originates from earlier devotional images from India which became popular across East Asia.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

“Divine beliefs”

Beginning with the worship of nature spirits over 2,000 years ago (including a fat, squat, terracotta figure spewing foliage, not unlike a medieval Green Man), it segues into each religion’s development of devotional art. En route, it explores how gods, spirit guides and divine beliefs have been represented, and adapted, up to the present day. And how these representations have been shared by each different belief system, and across the Indian Ocean to Southeast Asia and along the Silk Roads to China and Japan.

Short videos show how some of today’s estimated two billion believers of all three faiths carry out acts of worship and prayer: a Hindu grandmother and her granddaughter in Leicester, for instance (Hinduism is Britain’s third largest religious group, rather outnumbering its 25,000 Jains).

The 180 exhibits – which include drawings, manuscripts, hanging scrolls, silk paintings and richly carved sandstone tablets as well as a fossilised ammonite from Nepal – are absorbing, often exquisite. Many come from two major sacred sites: Amaravati and Ahicchatra, a 4th century temple complex in the north-central Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Others, in either pink sandstone or marble, represent Jain deities.

Ganesha made in Java from volcanic stone, about AD 1000–1200.

Hindu ideas and imagery flowed in both directions between India and Southeast Asia. The elephant-headed god Ganesha is part of Southeast Asia’s diverse religious landscapes. This sculpture shows Ganesha’s traditional attributes, such as his broken tusk, axe and prayer beads, along with some differences. Javanese artists often portrayed him with skulls, his feet together and carrying an empty bowl rather than one filled with sweets, indicating that varying communities understood and worshipped him differently.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

“Serene”

You could have a lot of fun just spotting the serpents: a snake goddess, five-headed snakes, cobra canopies… Among the most ancient deities to be worshipped (and feared) in India, they were believed to grant wealth, fertility and protection – as well as being able to kill with a single bite. The Hindu god Shiva is often depicted with a cobra coiled round his neck. Meanwhile for Jains, one bronze statuette from AD 1300 to 1400 shows the 23rd Jain tirthankara meditating under the snake hood sent to protect him from evil spirits.

Other highlights include a small gold reliquary inset with garnets and turquoise, dating to around AD100 and believed to show the oldest image of the Buddha in human form; an array of slender and serene Jain statues, representing universal compassion; and another Ganesha statue, found in Java and dating from around AD1100-1200. If you look closely enough, the elephant-headed god has such a sensitive, soulful, look in his eyes, you wonder how anyone can mistreat such wonderful creatures.

Seated Jain enlightened teacher meditating, about 1150-1200.

This marble figure depicts a Jain tirthankara (enlightened teacher). Tirthankaras are human, not divine, and the earliest certain representations of them in human form were shaped in Mathura, possibly in about the first century BC. Seated in meditation, the tirthankara has the sacred symbol of an endless knot in the middle of his chest.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

“Exuberant”

Then there’s a black stone lingam, representing the god Shiva in phallic form. Another statue shows him as ‘Lord who is half-woman’, with both an erect phallus and curvaceous breasts. Hinduism has never knowingly shied away from the erotic – as anyone who’s ever visited the temples at Khajuraho in the state of Madhya Pradesh will know.

Women’s reproductive power is also celebrated. In the Amaravati relief, for instance, the Buddha’s mother, Queen Maya, seems to give birth to him with voluptuous, sensual ease. Life, love, fecundity – they’re all on exuberant display here, as opposed to death, sin and sorrow.

Ancient India: Living Traditions, is at the British Museum in London until 19th October

britishmuseum.org

Top image: © The Trustees of the British Museum