Unearthed: The Power of Gardening, at the British Library – Review

By Clare Jenkins, June 2025

My father was a gardener, working around the Midlands initially for convents, then for ‘lords of the manor’ in their big houses. We grew up in tied cottages, always with lovely gardens he’d created himself, occasionally with vegetable patches. He also kept bees. So while we may have been short of money, we were never short of honey.

Dad would have identified strongly with some of the observations made by fellow gardeners in this engrossing exhibition about the rich and radical history, development and healing power of gardens. In one of a series of short films, made in collaboration with Lewisham’s Coco Collective community garden scheme, a man picking his own vegetables says: “We are part of the earth, and the earth is part of us.”

“Mindful”

A fellow CC gardener agrees. “I’m looking after this plant,” she says, “and then the plant is looking after me.” A third states simply: “This is self-help.”

My father, too, found solace in nature, had the greenest fingers of anyone I’ve ever known, and could reel off the Latin names of everything he saw and sowed. This, despite having left school at 14 and being hired by a local farmer in Scotland in the way Thomas Hardy wrote about in The Mayor of Casterbridge.

The films illustrate some of the powerful messages of Unearthed: that gardens can be simply functional (think of all those ultra-manicured, daisy-less lawns) or areas of beauty. But they can also be instrumental in improving people’s physical and mental health. After all, what can be more mindful than planting a seed, seeing the first shoots appear, then watching as the plant, herb, fruit or vegetable ripens until ready for picking.

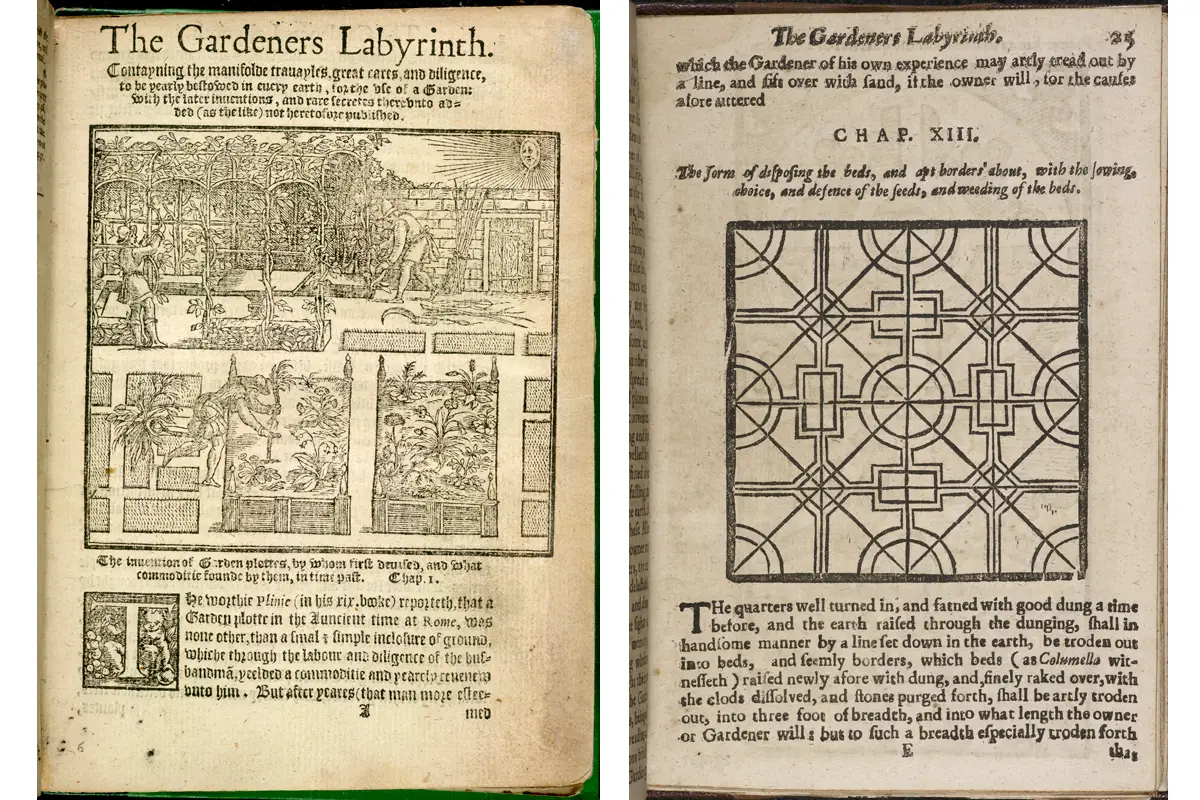

Images from Thomas Hill, ‘The Gardeners Labyrinth’. London, 1577. From the archive of the British Library

“Depended on the land”

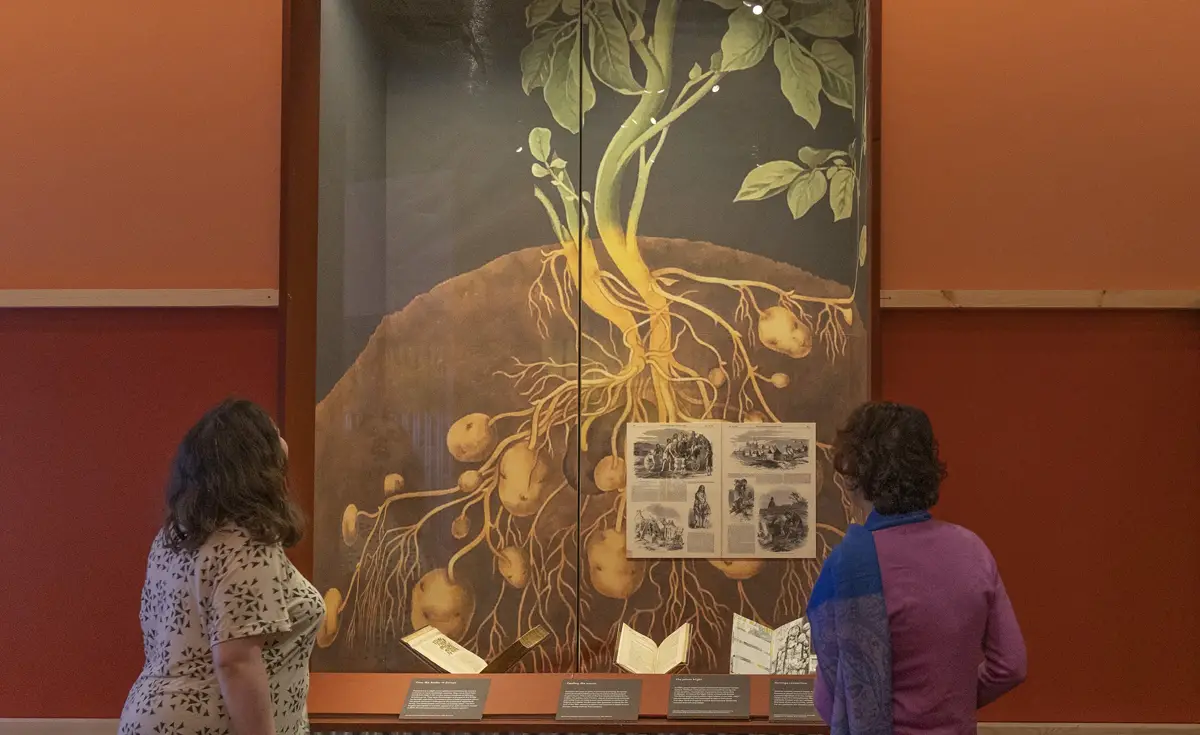

The exhibition starts conservatively enough, with medieval maps, woodcut illustrations and beautifully illustrated manuscripts, including the first printed gardening manual, The Gardener’s Labyrinth, written in 1558 by Thomas Hill.

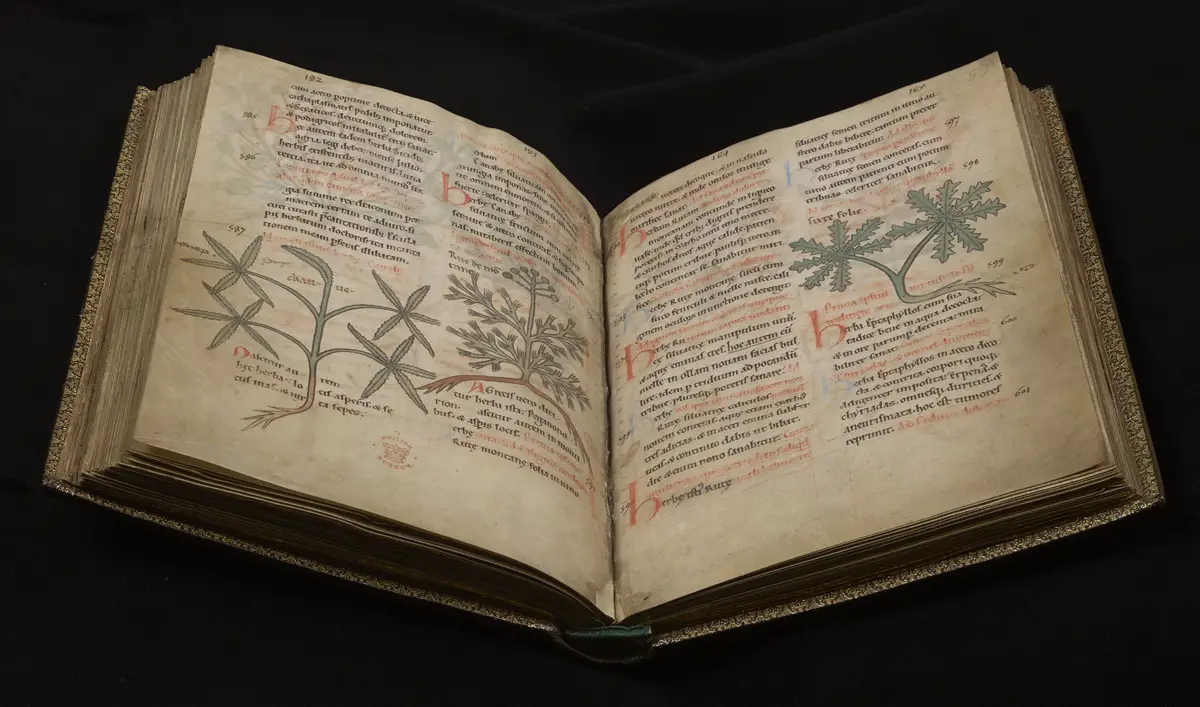

There’s a section on herbs, including the only illustrated collection of herbal remedies to survive from Anglo-Saxon England (dating from 1000-1025). There are medicines from the apothecary’s shop, a pestle and mortar, a recipe for how to treat scurvy, a 14th Century Persian version of the Greek book about medicinal plants, Materia Medica. And then another quote: “The earth can survive without us, but we can’t survive without the earth.”

For centuries, like my dad, people depended on the land not just for work but also for survival. On common land shared by rural communities, villagers could grow food – until the Enclosures effectively privatised them. A map from 1791 shows how shared land in one Buckinghamshire village was enclosed and transferred to wealthy residents, including the Rector, leaving just one small patch called ‘the Poor’s Allotment’.

Compilation of texts on medicines. Liège, about 1175. From the archive of the British Library (MS Harley 1585 f. 52.)

“Connected”

Gradually, during the Industrial Revolution, people had to move from their villages into towns and cities for work, often living in tenements and back-to-backs, with little room for gardens. Yet people still needed, as another Coco Collective gardener puts it, “to be connected to nature, to be connected to the ground.”

Allotments grew in importance during the First and Second World Wars, with the latter’s Dig For Victory campaign and Land Army Girls (my mother was one). By 1945, over one in five households had turned their gardens temporarily into allotments. Many town- and city-dwellers, of course, still have them: as another CC gardener says, “When I arrive here, I can feel goose pimples on the back of my neck and a big smile appears on my face, and there’s a truly beautiful feeling of – where else would I rather be to feel peace right now?” God can indeed be found in a garden.

There’s information about grow-your-own initiatives in prisons and refugee camps, and the garden design for Bethlem (or Bedlam) Royal Hospital asylum for the mentally ill. Information, too, about the development of green spaces in cities, the campaigns against encroaching urbanisation.

“Indigenous peoples and ecosystems”

One section looks at social resistance movements like the 17th Century Diggers and True Levellers who demanded land reform, protesting against the Enclosure Acts; the early 20th Century Garden City movement; and today’s guerilla gardeners and ecological campaigners who use seed ‘bombs’ to rewild wasteland and set up community allotments on derelict land. Literally sowing the seeds of change.

As Valerie Goode, the founder of the Coco Collective (which opened as a response to the pandemic, primarily for members of the local African community), says: “When you leave your food production in the hands of other people, you are leaving your health, your wellbeing, your sense of identity, in the hands of other people. When we reclaim our food, we reclaim our power.”

Elsewhere on show are the boots that Gertrude Jekyll, trailblazing gardener, writer and garden designers, wore for 40 years, and the world’s oldest mechanised lawnmower. There’s a mid-19th Century Wardian case: a mini travelling greenhouse designed to keep plants alive on long sea voyages during Victorian times. And, inevitably, there’s a discussion about the threat to indigenous peoples and ecosystems by the Imperial desire to ship plants (fabulous botanical illustrations of orchids and pineapples, by European, Indian, Chinese and Caribbean artists) back to Britain. Was this conservation, cultivation or colonial theft?

“Immersive”

Today, of course, we’re trying to reprise what our ancestors took for granted: taking back control of the land, recognising the loss of biodiversity, the importance of ecology. And so, while some people sacrilegiously dig up their front lawns to house their cars, others rewild patches of land, forego pesticides, respect No Mow May, do what they can for bees, birds and hedgehogs, allow daisies and dandelions to thrive. And, instead of buying supermarket fruit and veg, they grow their own.

The exhibition closes with a colourful, immersive installation by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg called Pollinator Pathmaker. Sit in front of it and allow yourself to see and hear the world from a bee’s perspective. Then go home and – like my father – get planting.

Unearthed: The Power of Gardening is at the British Library, Euston Road, London NW1 2DB, until 10th August

Top image: British Library Board