Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 – Review

By Clare Jenkins

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting shows a woman at an artist’s easel, brown apron over dark green gown, one hand cradling a palette, the other, raised, holding a fine paintbrush.

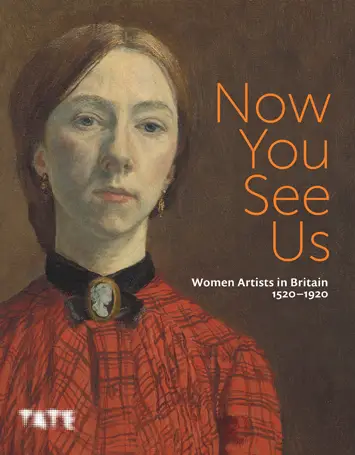

This 16th Century picture opened Tate Britain’s recent celebration of female artists over four centuries, Now You See Us. And it immediately set the scene for a fascinating exploration of women’s art from the Tudor court to Dame Laura Knight, Vanessa Bell and Gwen John, whose own self-portrait, gazing directly at the viewer, provided the image for both the exhibition poster and its accompanying catalogue.

The exhibition may have finished, but the book is a box of delights. Here’s Edmonia Lewis, first sculptor of Black and Native American descent to achieve international fame. Here’s Sarah Biffin, born without hands and initially an object of curiosity in travelling fairs, later appointed miniature painter to the Prince of Orange and his family in Brussels. Here’s Clare Atwood, also known as ‘Tony’, and her lovely work Terrace Outside the Priest’s House, which shows her ménage à trois partners Christopher St John (former lover of Vita Sackville-West) and Edy Craig, daughter of the actress Ellen Terry. Here are references to Joshua Reynolds’s sister Frances, Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s wife Laura, poet Alexander Pope’s wife Clara Maria, Thomas Gainsborough’s daughters…

But, of course, they were more – far more – than sisters, wives and daughters of.

“Always there”

Take Gentileschi herself. Born into an artistic family in 1593, she worked as an artist across Europe, including London. Raped by a family friend when she was 17, her reputation was subsequently overshadowed by the attack. No wonder she took artistic revenge through Biblical works such as Judith Beheading Holofernes and Susannah and the Elders, which shows two sexual predators spying on the naked Susannah.

As the book’s editor Tabitha Barber writes, Gentileschi’s ‘exceptional achievements were the very goals that women artists in Britain who came after her strove to attain: she was a professional who ran her own busy workshop, she was a member of an art academy, she made a career painting large historical and biblical subjects, she used female nude models for the creation of her works, and she was ranked as a serious artist, alongside men’.

Those threads run through this 200-page book. It charts the careers of over 100 women artists and the obstacles they navigated: prevented by fathers or husbands from selling their work, forcing them to retain their amateur status; forbidden access to professional training or life drawing; barred from membership of institutions… In the end, they set up their own societies and institutions, frustrated at seeing their work hung high or ‘stuffed into corners’ at the prestigious Royal Academy. The RA itself remained pretty much a men’s club until 1922, when it reluctantly accepted Annie Swynnerton as an associate member. She was nearly 80 at the time.

Yet women were always there. Portrait painter Mary Beale (1633-99), for instance, whose clientele included ‘members of the nobility, gentry families, Anglican churchmen, civil servants and City professionals’. As ever, it helped to be middle-class, monied – and married to a supportive man (Beale’s husband ran her commercial studio on Pall Mall).

The first women to exhibit their work at the Royal Academy included the Swiss artist Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), who arrived in London from Rome, set up her own studio and became a protegee of Joshua Reynolds, the leading portraitist of the day and President of the RA. Her paintings covered the Council Chamber ceilings in the RA’s new premises Somerset House, when it opened in 1780.

“Excluded from life classes”

Critics could be harsh about women artists’ work, calling Maria Cosway’s work, for instance, either mad or the ’weak dream of a sterile and fevered imagination’. Despite this, Cosway became the most high-profile woman painter to exhibit at the RA, showing 42 pictures there over two decades. They included the stunning Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, as Cynthia (1782), in which the controversial Chatsworth duchess is seen as the moon goddess emerging from silvery clouds into the night sky. Cosway’s husband, however, himself a society artist, refused to let her sell her work commercially.

She wasn’t the only woman discouraged from painting for profit. When in 1764, the 20-something Mary Black painted a vivid portrait of physician Messenger Monsey, she initially asked for £25 (half the amount charged by Joshua Reynolds), then half of that, only for Monsey to call her a ‘slut’ and ‘so saucy’ for being so bold as to expect payment.

Throughout the 18th and 19th Centuries, women artists were also excluded from life classes, only allowed into the RA Schools’ life drawing classes in 1893 – and then strictly segregated, with models demurely draped to keep their private parts private. Kaufmann herself managed to paint a male nude in the comfort of her own home – but only with her father present in the room.

Some artistic activities were regarded as suitable for women – among them needlework, watercolours or pastels and botanical illustration. Pastel, according to Joshua Reynolds, was ‘just what ladies do when they paint for their own amusement’. When Anna Mary Howitt painted fellow artist (and feminist campaigner) Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon as Boadicea, the influential art critic John Ruskin asked, “What do you know about Boadicea? Leave such subjects alone and paint me a pheasant’s wing.”

“Feminist visionary”

When the Slade School of Fine Art was founded in 1871, however, women were admitted on terms of near-equality with men. Among the students were brother and sister Gwen and Augustus John – whose careers took very different paths. And, by the turn of the 20th century, women made up a large proportion – sometimes over half – of students at art colleges. Yet there were still barriers and closed shops, and women often remained invisible in the art world.

When the Slade School of Fine Art was founded in 1871, however, women were admitted on terms of near-equality with men. Among the students were brother and sister Gwen and Augustus John – whose careers took very different paths. And, by the turn of the 20th century, women made up a large proportion – sometimes over half – of students at art colleges. Yet there were still barriers and closed shops, and women often remained invisible in the art world.

One groundbreaking work was Dame Ethel Wright’s magnificent 1912 portrait of the suffragette Una Dugdale Duval, whose marriage that year had caused a public scandal when, during the ceremony, she refused to promise to obey her husband. Wright herself was a feminist visionary who imagined ‘an idealised society based on individual freedom and social concord rather than prejudice’.

Yet it was to be another 60 years before the 1970s feminist movement began the archaeological dig into women’s art. As the book says, ‘Linda Nochlin’s well-known question – “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” – was a call to arms for art historians to research and reveal them.’

Now You See Us indeed.

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920, edited by Tabitha Barber, is published by Tate Publishing, 2024, price £32