The Gift of a Radio by Justin Webb – Review

By Helen Johnston

I first became aware of BBC journalist Justin Webb when he was working as a breakfast news presenter in the late ‘90s. It was one of those sweltering summer days we get occasionally and he suddenly complained that it was “stinking hot” in the studio. A pretty innocuous remark but it singled him out among the many posh and impassive presenters delivering the news at that time. An off-the-cuff remark to the viewers about working conditions – how daring! It made me smile.

I’ve no recollection of him again until a few years ago when I started listening to Radio 4’s Today programme. He is one of the regular presenters and an elder statesman now John Humphreys has retired, waking me and millions of others with the day’s news.

So, when I heard he’d written an autobiography I thought it would be interesting to find out more about him. And it was.

I had him boxed off as posh and privileged because he has what was once the only kind of accent we heard on the BBC. (Nowadays, thankfully, they let in people with regional accents, although they’re still in the minority). Webb grew up in Bath, went to boarding school, and his maternal grandad was Leonard Crocombe, a distinguished journalist chosen by Lord Reith to be the first editor of the Radio Times. So far, so upper middle class.

Except it’s not as straightforward as that. He was an only child, brought up by his mum Gloria, an insufferable snob, and his stepdad Charles, who was mentally ill. One day when BBC newsreader Peter Woods was on the television Webb’s mum told him he was his biological father. She’d had an affair with him while he was married and he wasn’t a part of Webb’s life.

Strangely, despite Webb following in Woods’ journalistic footsteps at the BBC, he never sought out his father and never met him.

Webb admits that as a young child he wished Charles dead because he was aware that life without him would be so much easier. Yet when Charles does eventually die years later, Webb records it matter-of-factly and gives nothing away about how he felt. Was it a relief after all of those years, did he grieve for him at all? He doesn’t tell us.

Webb was aware growing up that he didn’t have a male role model he could look up to, turning instead to watching the Bath rugby team to try to discover what it was to be a man. Webb has three children of his own but doesn’t tell us about his relationship with them. Does he think he’s a good father himself? Perhaps he feels unable to judge and doesn’t like to presume.

“Plenty of dry humour”

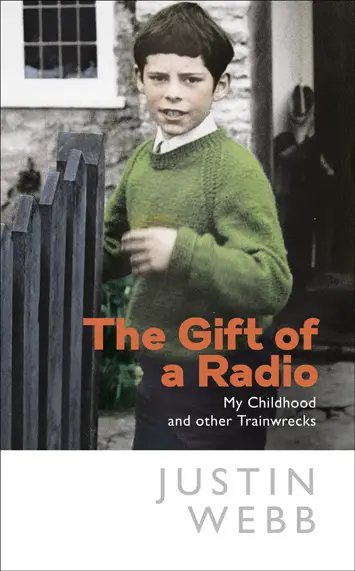

There are no family photos in the book, the only one is on the front cover, a shot of Webb as a young boy looking slightly confused. He explains in the book that this expression is because he wasn’t used to having his photo taken and was wondering why it was happening.

There are no family photos in the book, the only one is on the front cover, a shot of Webb as a young boy looking slightly confused. He explains in the book that this expression is because he wasn’t used to having his photo taken and was wondering why it was happening.

The lack of photos means we don’t get to see his mum, the biggest influence on his life and character. It’s clear he adored her (and she him) but that doesn’t mean he was blind to her faults, namely her distaste for the working class and their unmannerly ways. She looks down on the neighbours and anyone with a single syllable name, hence her instant dislike of Don, the hapless man from the Bath branch of the Labour Party who tried to sign her up during a period when she was, oddly, into Maoism.

She also turned to the Quakers and decided to send her son to Sidcot School, a boarding school run by them about 40 minutes from the Webb family home. The conditions were harsh (no hot water) and Webb says several times that the staff didn’t much care about actually educating their pupils. For instance, he was allowed to give up science.

At least at school he was able to meet other children his own age and, eventually, make friends, something denied him at home where his solitary pursuits included obsessing over his train track. He was aware he was missing out on something, and his mother must have known this too, realising he needed to escape the claustrophobia of her love and their circumstances.

In all then, it wasn’t so much a deprived childhood as a lonely and odd one. Webb took his cherished radio to boarding school as a comfort, little knowing that one day his own voice would be listened to by millions, maybe some of them taking comfort from their radio too.

The tale of his childhood is a tragicomedy. It’s very well written, of course, and there is plenty of dry humour about his parents’ foibles. His mum refusing to send him to one local school because they boasted they had the children of doctors there (the boasting was the problem, such a lower-class thing to do). His stepdad’s compulsion with replacing the garage doors on a regular basis and buying endless padlocks to keep them secure.

And yet there’s a sadness there too, for the little boy trying to make sense of this strange childhood. Webb writes with a certain detachment, almost as though he’s reporting on someone else’s life. When he recounts being in a coach crash in which a passenger dies there’s no account of how it affected him. Did he have flashbacks, was he able to travel by coach again? Maybe it’s the stiff upper lip coming into play.

There is some reflection at the end of the book but Webb is philosophical and certainly there’s no self-pity. He’s made a success of his life. Whether that’s because of, or in spite of, his upbringing is open to debate.

‘The Gift of a Radio’ by Justin Webb is published by Doubleday, £16.99 hardback