The Civil War Battle of Leeds, 1643

By Harry Bratley

When, on 22 August 1642, King Charles I raised his standard at Nottingham, the King’s dispute with Parliament became the English Civil War, a conflict that, for nine long years, ripped the nation apart and left the soil of England steeped in the blood of its sons and daughters.

Like most towns during the Civil War, Leeds had its share of troubles. At the outset of the war, the town became a stronghold for the Royalists, held by military troops under the leadership of Sir William Saville. However, all this would change when, on 23 January 1643, the town was successfully seized by Parliament’s forces.

Although the Parliamentarian army of ‘Roundheads’ is forever linked with Oliver Cromwell, in Yorkshire the war was all about one man – Sir Thomas Fairfax. Although he had been knighted by Charles I in 1641 to secure his support, this backfired on the King when Fairfax’s allegiances changed and, by 1642, he was serving as second-in-command to his father, Ferdinando, the 2nd Lord Fairfax of Cameron, commander of the Parliamentary army.

To keep the threat of combat away from the county, Yorkshire aristocrats, rather naively perhaps, persuaded the leading men on both sides to sign a neutrality treaty on 29 September 1642, with an agreement to disband their troops and keep the peace. However, the treaty was soon discarded when, less than a month later, on 23 October 1642, the Royalist army marched into Leeds.

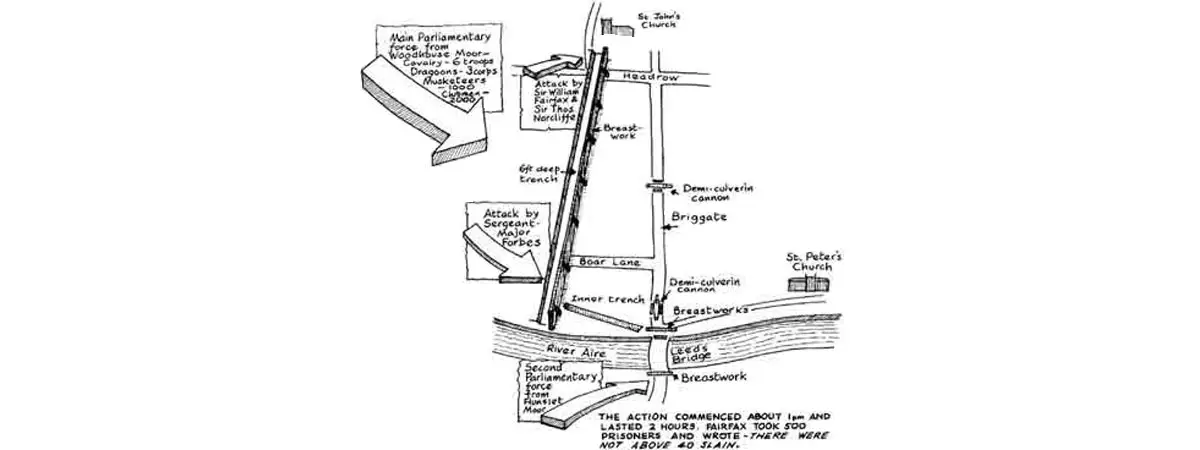

This occupation, however, was short-lived. Although the Royalist forces under Sir William Saville had seized the West Riding towns of Leeds and Wakefield without opposition, Saville met resistance when he attempted to storm Bradford on 18 December 1642. Reinforced by volunteers from the surrounding area, the citizens of Bradford drove them back, forcing the Royalists to retreat to Leeds. There, the task of building the Royalist defences in Leeds fell to Saville. To strengthen their command of the town, he constructed a six-foot-deep defence trench in an arc around the western side of the town, from St John’s Church down to the river.

“Surrender the town”

These new defences would soon be tested by Sir Thomas Fairfax, and although the forces under his command were small, he was keen to retake Leeds for the Parliamentarian cause. Writing to his father, Lord Fairfax, on 9 January 1643, he declared that “these parts grow very impatient of our delay in beating [the Royalists] out of Leeds and Wakefield”. The general’s intention was simple: to take the town of Leeds. Only a small matter of 2,000 Royalist soldiers stood in his way.

Fairfax’s letter evidently brought a decisive reply from his father, and on 23 January 1643, an enlarged Parliamentary army, many only recently recruited, made its way towards Leeds. The army’s journey towards the town, however, was not without difficulty. Kirkstall Bridge had been destroyed as part of the town’s defences, forcing Fairfax’s troops to cross the River Aire at Apperley Bridge and proceed to Woodhouse Moor, which, due to heavy rain, was difficult to cross. This compelled them to move south of the river onto Hunslet Moor, with another large group basing themselves northwest of the town, near St John’s Church.

Once his army was in position, Sir Thomas Fairfax sent a trumpeter to Sir William Saville, inviting him to surrender the town, to which Saville replied that he did not “give answer to such frivolous tickets”. He refused to surrender, and the Battle of Leeds was the unavoidable consequence.

That afternoon, in a heavy snowstorm, the battle began. Fairfax assaulted the town from his two attack points, crushing the 2,000-strong Royalist army, with many meeting their death by drowning while escaping across the river. Fairfax’s account of the battle recounts that “every commander gave charges and command to encourage their men, who being mightily emboldened by their valiant leaders, performed with admirable courage. When bullets flew about our men’s ears as thick as hail, they made way into the town and got possession thereof. There were not above forty slain, whereof ten or twelve at the most on our side, the rest on theirs. Sergeant-Major Beaumont, in his flight endeavouring to cross the river to save his life, lost it by being drowned therein; and Sir William Saville in his flight also crossing the same river, hardly escaped the same fate”.

“Fresh supply”

The taking of Leeds was seen as a great triumph and was seized upon by Parliament, which, as was typical during the Civil War, published propaganda leaflets celebrating Fairfax’s victory.

Although the battle was quick and decisive, within a matter of weeks circumstances changed when the King’s wife, Henrietta Maria, known as Queen Mary, arrived from the Continent with a convoy of additional troops, ammunition, and, most importantly, a fresh supply of money. This enabled the Earl of Newcastle to attack the Parliamentarian army in Yorkshire, prompting Lord Fairfax to mobilise his forces in Leeds. On his father’s instructions, Thomas Fairfax made a show of strength at Tadcaster. However, on 30 March 1643, it all went terribly wrong when, on their return journey across Seacroft Moor, they fell prey to the Royalists under the command of General Goring. There were many casualties, and 800 Roundhead prisoners were carted away to York. Fairfax escaped with some of his surviving troops to Leeds, quoting that the Battle of Seacroft was “the greatest loss we ever received”. This was a real wake-up call for the Parliamentary forces in the North.

With Leeds now effectively under siege, Newcastle could easily have retaken the town. However, after unsuccessfully trying to broker a treaty, the Royalists instead retreated to Wakefield. Afraid of another siege, Fairfax persuaded Parliament to grant him £7,000 to reinforce his army, and the Royalists missed their opportunity to wipe out the fighting wing of the Parliamentarian army in Yorkshire.

“Orderly retreat”

Intending to take prisoners that could be traded for his own soldiers seized at Seacroft, Sir Thomas Fairfax attacked the Royalists at Wakefield on 21 May 1643. This was a complete success, driving the Royalists out. However, they regrouped, and on 30 June 1643, their 10,000-strong forces repelled a surprise attack by Sir Thomas Fairfax at Adwalton Moor near Bradford. The Earl of Newcastle’s victory once again left the Royalists in control of Yorkshire. Following the battle, Sir Thomas Fairfax escaped to Leeds, where his father was desperately trying to organise an orderly retreat to Hull, resulting in Newcastle’s Royalist forces now dominating not only Leeds but the whole of Yorkshire.

By now, the war was going badly for Parliament until a major turning point in the conflict in late 1643. Parliament made a deal with the Scots, who agreed to support the English Parliamentarians on the condition that the Church of Scotland’s “Solemn League and Covenant” Presbyterian Charter was adopted in England and Ireland. The arrival of the Scottish Army, fighting for Parliament in January 1644, saw the Parliamentarians once again retaking not only Leeds but the whole of Yorkshire, which they would then control for the duration of the war.

The Civil War ended with what many in 1642 could probably have never considered – the trial for treason of Charles I and his execution on 30 January 1649.

Drawings are artist’s impressions