1842 – Chartists, General Strike and ‘Plug Riots’ in Leeds

By Harry Bratley

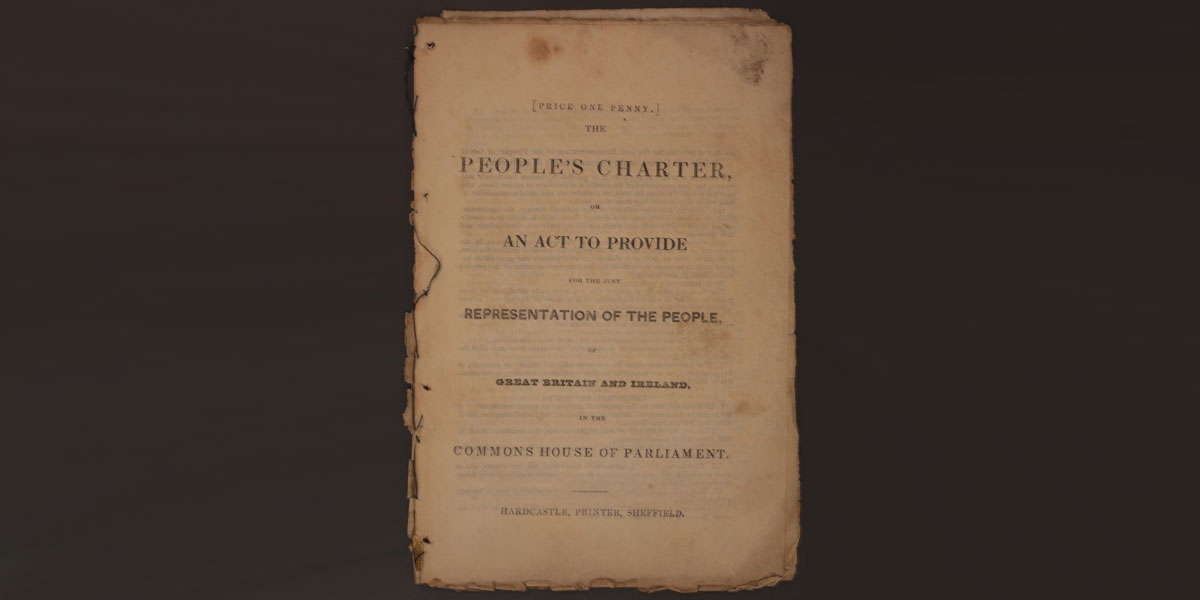

Written in 1838, mainly by William Lovett of the London Working Men’s Association, the People’s Charter stated the ideological basis of the Chartist movement. Launched in Glasgow in May 1838 at a meeting attended by an estimated 150,000 people, it was presented as a popular-style Magna Carta. It rapidly gained support across the country and its supporters became known as the Chartists.

A petition, decided at Chartist meetings across Britain, was brought to London in May 1839 for Thomas Attwood to present to Parliament. It boasted 1.25 million signatures, yet it was rejected by Parliament. This triggered unrest, which was quickly crushed by the authorities. A second petition was presented in May 1842; this time it was signed by over three million people, but again it was rejected. Further unrest followed, leading to the General Strike and ‘Plug Riots’.

“Nationwide movement”

The People’s Charter detailed six key points that the Chartists believed were necessary to reform the electoral system and thus alleviate the suffering of the working classes – these were:

- Universal suffrage (the right to vote)

When the Charter was written in 1838, only 18 per cent of the adult male population of Britain could vote. The Charter proposed that the vote be extended to all adult males over the age of 21. - Vote by secret ballot

Voting at the time was done in public using a ‘show of hands’ at the ‘hustings’. Landowners or employers could therefore see how their tenants or employees were voting and could intimidate them and influence their decisions. A secret ballot would protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. - No property qualification

At the time the Charter was written, potential members of Parliament needed to own property of a particular value. This prevented most of the population from standing for election. By removing the requirement of a property qualification, candidates in elections would no longer have to be selected from the upper classes. - Payment of members

MPs were not paid for the job they did. As most people required income from their jobs to be able to live, this meant that only those with considerable personal wealth could afford to become MPs. The Charter proposed that MPs should be paid an annual salary of £500. - Equal representation

A ‘pocket’ borough was a parliamentary constituency owned by a single wealthy patron who controlled voting rights and could nominate the two members who were to represent the borough in Parliament. There were, at the time, great differences between constituencies, particularly in the industrial north where there were relatively few MPs compared to rural areas. The Chartists proposed the division of the United Kingdom into 300 electoral districts, each containing an equal number of inhabitants, with no more than one representative from each district to sit in Parliament, thereby securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors. - Annual Parliaments

As it stood, a government could retain power as long as there was a majority of support, making it very difficult to replace a bad or unpopular government. Annual parliamentary elections would present the most effective check against bribery or intimidation, as no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal male suffrage voting every twelve months.

Chartism was a nationwide movement brought about by Parliament’s uncaring attitude to the working classes. This was reflected in the failure of the 1832 Reform Act to make Parliament representative of the working classes; the failure of the 1833 Factory Act to address the demand for a maximum ten-hour working day; and the imposition of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which centralised the existing workhouse system to cut the costs of poor relief and discourage perceived laziness. This Act resulted in the infamous workhouses of the early Victorian period: bleak places of forced labour and starvation rations.

“Insurrection”

Leeds was one of the most important centres of Chartist propaganda in the north of England, where Fergus O’Connor, the Chartist folk hero, published the Northern Star, which by 1839 had a national circulation of 50,000. Notably, the Northern Star gave effective voice to the Chartist movement in Leeds, carrying details of local radical meetings and highlighting social issues, giving O’Connor significant influence over Chartism in Leeds and the wider Yorkshire area. The years from 1839 to 1842 were ones of severe depression in the local economy. The destitution and desperation this induced amongst the working classes rallied great support for O’Connor’s calls for the use of ‘physical force’ to achieve the objects of the Charter.

In 1842, with many people suffering hardship due to severe recessionary economic conditions, and given Parliament’s intransigence to the demands of the People’s Charter, poverty boiled over into a level of militancy that many believed could result in a popular uprising. The General Strike of that year, inspired by the Chartist movement together with demands for better pay and working conditions, was also branded the ‘Plug Plot Riots’, so named because mills were stopped from working by the removal, or ‘drawing’, of a few bolts or ‘plugs’ in the boilers to prevent steam being raised. The insurrection soon spread to nearly half a million workers throughout Britain, and represented the largest single exercise of working-class strength in the nineteenth century.

By July 1842, the effects of the economic depression and rising unemployment in Leeds were so great that the town was braced for unrest as the ‘Plug Riots’ swept through Lancashire and into Yorkshire. The council and magistrates prepared to safeguard the town against any disorders that might occur. Thirty thousand staves – strong sticks used as weapons – were provided for special constables; the streets were cleared early in the evenings and public houses were forced to close at 8pm.

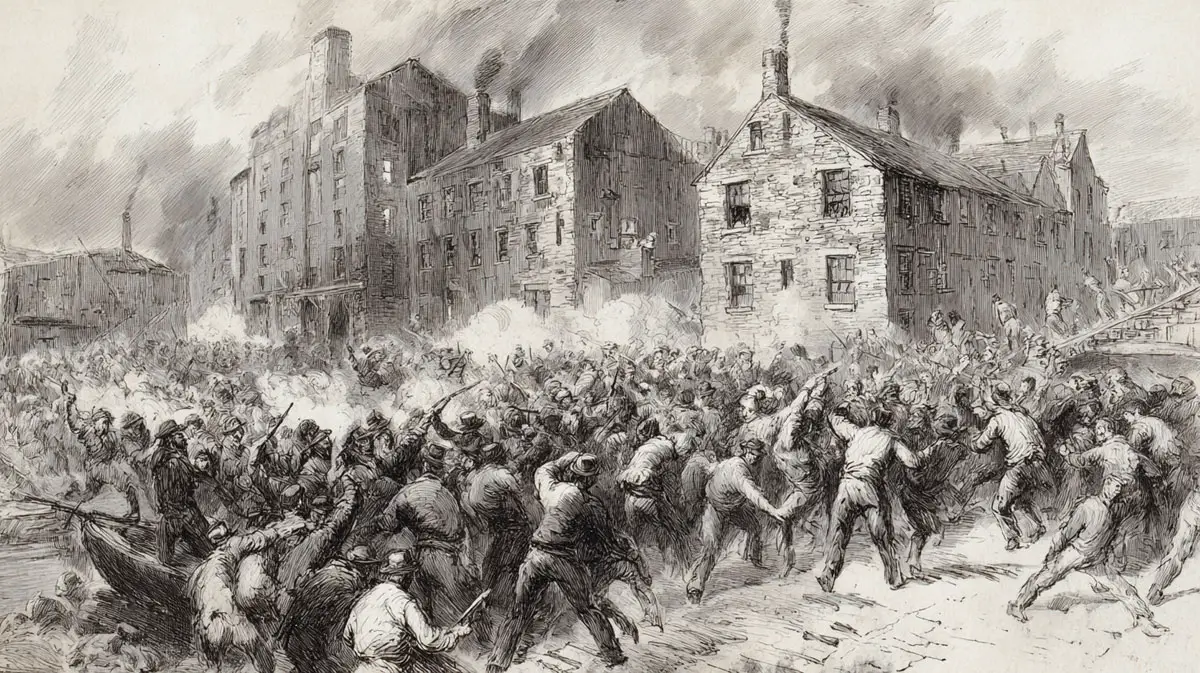

On 17 August, riots finally broke out, mainly in Hunslet and Holbeck. News was received that a mob had stopped several mills in Holbeck, and a large force – consisting of 1,600 additional special constables in support of the regular police, the 17th Lancers and the Yorkshire Regiment – raced to the area. Around a thousand rioters had marched to the Holbeck premises of J. G. Marshall, where workmen bravely defended the boiler at Temple Mill.

“Mob dispersed”

Although the mob did break in, they could not find the boiler plugs; however, they did manage to stop the engines at Benyon’s Mill. Having met the 17th Lancers on Water Lane, been read the Riot Act and threatened with artillery, the mob dispersed. They then continued to Maclae and Marshall’s Mill on Dewsbury Road, where a number entered by the watch-house door and opened the large gates. At this moment, Mr Read, the chief constable, rode into the yard, where he was quickly unhorsed but managed to beat off the mob and have the gates closed.

A large force of special constables arrived and duly arrested thirty-eight people who, at trial, were given sentences ranging from transportation to up to ten years, or being bound over to keep the peace. Although the riot was linked with Chartism, there is no evidence that leading Chartists in Leeds were directly involved.

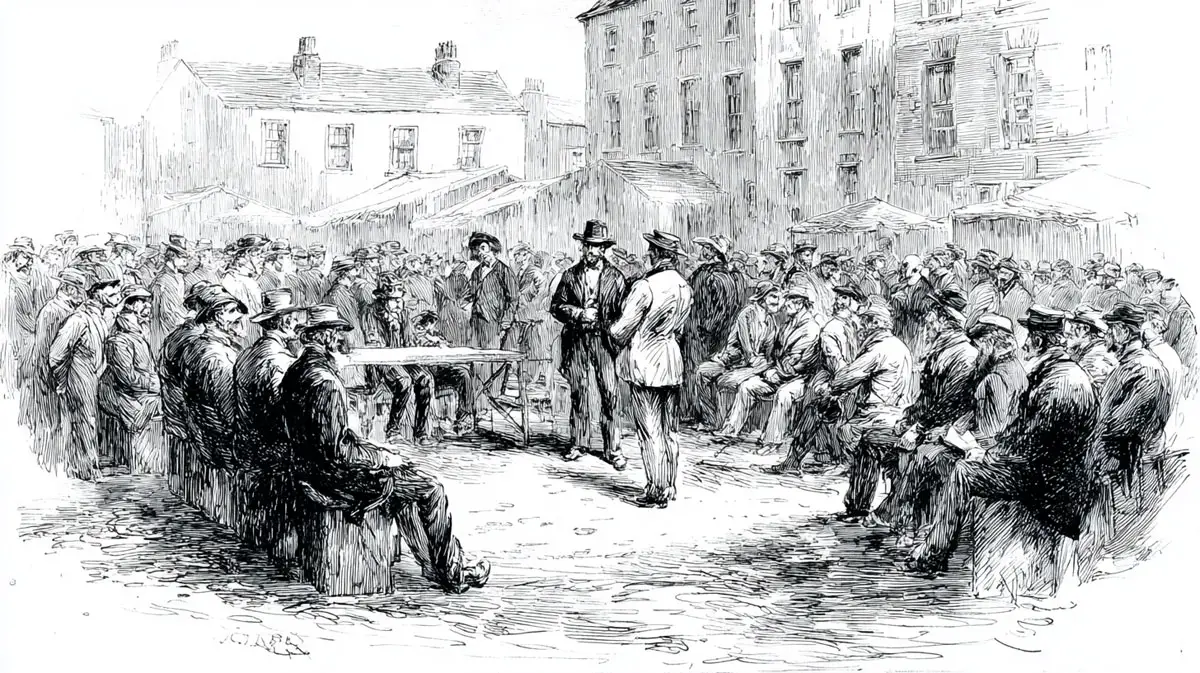

The next day, the Chartists and their followers marched again and successfully shut down collieries, factories and mills. They then proceeded to hold a large meeting on Hunslet Moor. The police were called in, along with 600 soldiers, and they stopped the meeting.

Further trouble broke out when a huge gathering of between 8,000 and 10,000 people marched through Calverley, Stanningley, Bramley and Pudsey, removing boiler plugs at all the mills and factories along the way. When they reached Bank’s Mill in Far Pudsey, the workers refused to stop work and the crowd proceeded to destroy the place. When a small military contingent arrived to disperse the mob, the people moved as one mass to attack the soldiers, who wisely turned their horses around and retreated.

“Troubled areas”

Prince George, the grandson of George III and cousin of Queen Victoria, and colonel of the 17th Lancers, was the military commander in Leeds at the time but, as the Leeds Times reported, he unfortunately did not acquit himself very well on the day. Making his appearance in full dress uniform on Camp Field, Holbeck, where the Riot Act was being read to a few straggling people, the Prince drew his sword and waved it about with great gallantry.

The Prince talked a good deal, in very bold and decided language, declaring his determination to resist the mob in their attempts to stop the mills. While Prince George was speaking, with his sword thus drawn, a few lads got into Messrs Titley, Tathum and Walker’s engine house and pulled the plug out, whereupon the works were immediately stopped. The crowd laughed, but Prince George was very angry. However, he withdrew his body of troops back to the Court House, without having achieved any decisive victory. Embarrassingly, on the following day, General Brotherton assumed command, replacing Prince George.

The General Strike and ‘Plug Riots’ were short-lived. Although the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, favoured a non-intervention approach to the problem, the Duke of Wellington argued for troops to be sent to deal with the strikers and rioters. Eventually, Peel agreed with Wellington, and the army was despatched to the troubled areas, where organisers of the strikes and several Chartist leaders were detained.

Out of 1,500 people arrested, seventy-nine were found guilty and sentenced to between seven and twenty-one years’ transportation to Australia. Although the campaign lost its central leadership, some 500,000 workers remained on strike through the end of August and into September, with the most persistent holding out until the end of September before settling with employers.

“Improved working conditions”

So, what did the General Strike and ‘Plug Riots’ achieve? In all cases, strikers prevented proposed wage cuts at their factories. Some had to settle for this small victory; in other cases, owners granted wage increases from pre-strike levels. Although the campaign failed to secure the People’s Charter, one of the initial goals – better pay and workplace conditions – was largely achieved. In 1844, Parliament passed the Factory Act, which improved working conditions for women and children, who made up a substantial percentage of the industrial workforce at this time.

Chartism survived and thrived as a movement, later reaching its apex of influence in 1848. Trade unions continued to exert their force periodically, but would not be legalised until 1871 to enable workers to combine. Under the provisions of the Trade Union Act 1871, trade unions gained legal status. As a result of this legislation, no trade union could be regarded as criminal for being in restraint of trade (withdrawing their labour), and trade union funds were protected.

Although trade unions were pleased with this Act, they were less happy with the Criminal Law Amendment Act, passed the same day, which made picketing illegal. By 1918, five of the Chartists’ six demands had been achieved – only the stipulation that parliamentary elections be held every year was unfulfilled.

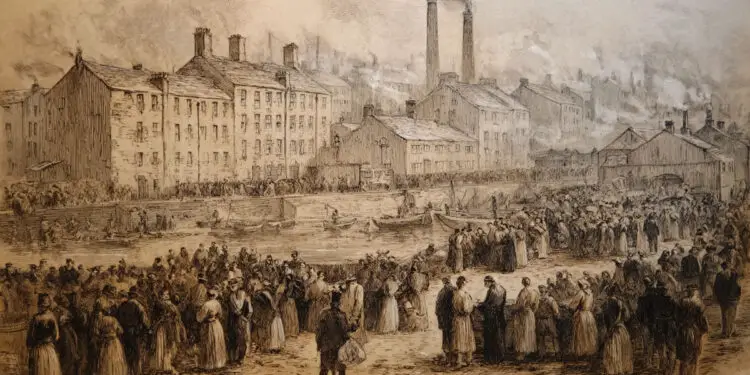

images are representational

Key takeaways:

In 1842, after Parliament rejected a second Chartist petition, unrest escalated into a general strike – the ‘Plug Riots’.

In Leeds (Hunslet and Holbeck), mills were stopped by pulling boiler plugs; troops and special constables intervened.

Dozens were arrested; wage cuts were largely prevented; the Factory Act 1844 improved conditions.

Chartism endured, achieving five of six Charter aims by 1918 (not annual parliaments).

FAQ

What were the Plug Riots?

Industrial stoppages in 1842 where workers halted steam power by pulling boiler plugs during a Chartist-inspired general strike.

When did unrest reach Leeds?

Mid-August 1842, with notable clashes on 17 August in Hunslet and Holbeck.

Why did the strike happen?

Economic depression, wage cuts and Parliament’s rejection of Chartist petitions.

What changed afterwards?

Proposed wage cuts were mostly blocked; the Factory Act 1844 improved conditions for women and children; Chartism continued as a national movement.

How many signed the petitions?

~1.25m in 1839 and over 3m in 1842.