Richard, Duke of York, and the Battle of Wakefield

By Paul L. Dawson

If Wakefield is known for any military event, it is for Richard, 3rd Duke of York’s death, supposedly on 30 December 1460. The prelude to these events was the removal of Richard II (r. 1377–99) from the throne and his replacement by Henry Bolingbroke as Henry IV (r. 1399–1413). Civil war ensued, resulting in the Battle of Shrewsbury (21 July 1403), which secured Henry IV’s position as king.

Henry IV was succeeded by his son, Henry V (r. 1413–22), who used the war with France to unite the elite behind him. He narrowly escaped a coup led by the Earls of Masham, Northumberland, Cambridge and others in 1415, in what became known as the Southampton Plot. Interestingly, at the time of the plot, the Earl of Masham was resident at Sandal Castle, having lived there since 1411. He had married the widow of Edmund Langley, Duke of York.

“Dynastic claim”

Henry V’s victory at Agincourt secured Lancastrian power, but his early death in 1422 and the succession by his son, Henry VI (r. 1422–61 and 1470–71), sparked a significant constitutional crisis, now known as the Wars of the Roses. Henry VI suffered acute mental health issues and proved almost incapable of rule.

By 1450, the defeats and failures of the English royal government in France had boiled over into serious political unrest, culminating in Jack Cade’s Rebellion. Richard, Duke of York, made a bid for power—not to become king, but to be recognised as Henry VI’s heir (at this point, Henry had been childless after seven years of marriage). York’s grandfather was Edward III, giving him the same dynastic claim to the throne as Henry Bolingbroke, later Henry IV.

At the Battle of St Albans on 22 May 1455, York killed many key leaders of the opposing House of Lancaster, leaving Lord Clifford, Henry Beaufort, the Earl of Somerset and others seeking revenge for their fathers’ deaths. Following the battle, Henry VI was placed in Yorkist custody along with his two-year-old son, and York was made Constable of England.

Following the death of Richard, Duke of York, at Pontefract, his son Edward became king. The Act of Accord in October 1460 had made the Duke of York and his heirs the rightful successors to the English throne, bypassing the son of Henry VI. With the duke’s death, Edward inherited the claim and secured the crown at the Battle of Towton. He later spent a night in Wakefield in 1471 during his campaign to retake the throne following the Readeption of Henry VI.

“Severe punishment”

The years 1456 to 1459 were marked by political turmoil bordering on civil war. In June 1459, a Great Council was summoned to Coventry. York, the Nevilles and other lords refused to appear, suspecting that the armed forces gathered the previous month were intended to arrest them.

Their fears were justified. In December 1459, York and the Earls of Warwick and Salisbury were attainted—their lives were forfeit, their lands reverted to the king, and their heirs disinherited. This was the most severe punishment a member of the nobility could suffer, placing York in the same position as Henry of Bolingbroke had been in 1398.

Now in Ireland with an army, York realised that only a successful invasion of England could restore his fortunes. Assuming he was victorious, York had three options: to become protector again, to disinherit the king’s son so that he would succeed, or to claim the throne for himself.

This eighteenth-century engraving is based on an image of Sandal from 1564 but bears no real resemblance to reality. The motte on which the keep stands is omitted; the barbican is reduced in scale; and the stairs from the keep gatehouse up the slope of the keep are impossible to reconcile with the castle’s actual ground plan revealed through archaeology. Moreover, the castle was not surrounded by woodland, nor does it sit on a large hillock as shown. The woods depicted are entirely artistic licence and have contributed to a centuries-long myth about the Battle of Wakefield. The original ink, chalk, and watercolour image—housed in the National Archives, Kew—is a workshop piece, drawn not from life but from field sketches and notes, later reworked. Neither image, alas, offers an accurate or reliable depiction of Sandal.

“Claiming the throne”

In early summer 1460, the Earl of Warwick, backed by the Earl of Salisbury, launched one of the last successful invasions of the country – the last being arguably in 1688. It was at the head of a French army that Henry VII would later win the throne in 1485. Warwick’s forces were bolstered by the Calais garrison – perhaps the only professional force of soldiers in the country at the time.

Warwick and Salisbury’s victory at the Battle of Northampton gave them control of the hapless king. York landed from Ireland in September and proclaimed himself king. Henry VI had proven incapable of governance, and the Lancastrian faction had grown powerful and wealthy in the absence of strong leadership.

York blamed Henry VI for the loss of French possessions and the economic crisis gripping the country. He believed that by claiming the throne, he could save the nation from what seemed like an inevitable invasion from France or Scotland. France had collapsed as a military power due to a weak monarch, which had enabled Henry V’s earlier conquest – York feared the same outcome for England.

A strong king was needed, and Henry VI was clearly not up to the task. Parliament and the House of Lords agreed. The Act of Accord, passed in the October Parliament, named Richard, 3rd Duke of York, as heir to the throne. It also specified that any act of aggression or malice against York – or the king – would henceforth be considered treason.

Queen Margaret, believing she had lost the war before it had even begun, pleaded with her uncle, Charles VII of France, for asylum. Yet it was not to France that she fled, but to Scotland, accompanied by the Bishops of Lichfield and Carlisle, the Earl of Exeter, the Duke of Devon, and other nobles.

Richard, Duke of York (1411–60), was heir to the throne. His personal ambition, combined with the failure of his rival, the Earl of Somerset, to retain territory won by Henry V in France, and the effects of a Europe-wide economic recession, led to the Wars of the Roses. His sons, Edward and Richard, became kings of England, and his granddaughter became the queen of Henry VII.

“Smoking ruin”

In Yorkshire, the Earl of Northumberland, York’s sworn enemy, had refused to accept York as heir. He began killing leading Yorkists and destroying their lands and property. Based at Pontefract Castle, the earl burned Sandal Castle to the ground, denying York a power base in the north. York was commissioned by Parliament to end Northumberland’s reign of terror, and the destruction of Sandal and the ravaging of the vast manor of Wakefield was an act of terror and resource denial. Both the court rolls of the manor of Wakefield and archaeological excavations of the castle show that the buildings in the bailey were destroyed by fire. The castle remained uninhabited until 1843.

To confront Northumberland, who had also taken over Wressle Castle and nearby Spofforth, the Duke of York and his ally Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, left London in early December, a few days after Parliament had been prorogued, taking with them only a small force. York was accompanied by his household and an entourage filled with lawyers. His goal, as in 1454, was to enter York and hold petty sessions to bring the violence to an end. Protected by the law of treason, York felt himself invincible.

York arrived in Wakefield on Christmas Day 1460 to find Sandal a smoking ruin – it is believed he arrived from Conisbrough. He expelled the small garrison left by Northumberland and appointed his own officers to run the manor. Lodging in the precursor to the Moot Hall – the Earls Hall, or medieval manor house of the then town – records of the manor of Wakefield (now inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Register) tell us that the duke’s household consumed one ox, six quarters of beans (16s 8d) and five quarters of oats (£10 2s 8d). Having dispensed local justice, York left the Moot Hall early on 29 December.

Where fountains play in 2025 was the site of the town’s gallows in 1460. Known as ‘Bitch Hill’, it was here that followers of Richard, Duke of York were murdered on 30 December 1460, having been captured in combat the day before.

“Taken prisoner”

According to an eyewitness, on leaving Wakefield (reportedly heading to York), York’s household and baggage were ambushed by men loyal to the Earl of Northumberland. In the fighting, Richard Anson, MP for Hull, was killed; Sir Thomas Harrington was mortally wounded; his son was killed; and John Sclatter suffered “great injuries and mutilations suffered in the wars of our noble father at Wakefield, where he lost his right hand and badly injured the other, so that he may neither clothe nor feed himself”.

After a short skirmish, York and his household were captured and taken back to the Moot Hall. The battlefield itself lies somewhere under the City Fields development. The land in question was owned by Lionel, 6th Baron Welles – an enemy of York since the Battle of Blore Heath, where he had been taken prisoner by the Yorkists.

Early on 30 December, the Earl of Northumberland and Lord Clifford began executing their prisoners – possibly in Manor House Yard or the Bull Ring, where the town’s gallows stood in 1460. Executed in the Bull Ring were Sir Edward Bourchier, William Bonville, Sir James Strangeways, Richard Hansard, and Geoffrey Southwarth. Their bodies were dumped in a mass grave outside what is now the cathedral. York, however, was still alive. Meanwhile, the Lancastrians “proceed to trash” the surrounding countryside, driving cattle, pigs, and other livestock to Pontefract. Sandal Castle was set ablaze.

Erected at the end of the nineteenth century, reportedly on the spot where the Duke of York was killed in battle on 30 December 1460, the cross is historically inaccurate. Archive evidence shows the battle was fought on 29 December and that the duke was murdered in Pontefract. The cross has nothing to do with the battle and is a work of whimsy.

“Hacked to death”

Some of the Yorkist high command escaped the initial carnage but were captured later that evening and taken to Pontefract. The prisoners were held in St Richard’s Friary. Early on 31 December 1460, Andrien Treslot murdered the Duke of York. Among the other prisoners in the friary was the seventeen-year-old Earl of Rutland, who was executed by Lord Clifford. William Plumpton then executed the Earl of Salisbury and his son, Thomas. Also hacked to death at Pontefract was Londoner John Harrowe. Parliament posthumously convicted Northumberland of murder in November 1461 – he and much of his household had been killed at Towton. The Earl of Salisbury’s widow took legal action against those who survived Towton at the court of King’s Bench, which found them guilty.

Sometime on 2 January, the Earl of Northumberland left Pontefract for Beverley, carrying with him the heads of York, Salisbury and Rutland. Their bodies were dumped in a grave at St Richard’s Friary. Clifford threatened to kill the surviving members of Salisbury’s household but settled instead for physical violence and extortion.

Wakefield bridge and chantry chapel. Myth says this is where the Earl of Rutland was killed, but he was actually murdered in Pontefract.

“Slung on a horse”

The Battle of Wakefield marked a significant turning point in the code of chivalry. In previous conflicts, the bodies of nobles had been respected, but this was not the case at Wakefield. The mutilated cadavers of the Yorkist nobility became weapons in a brutal propaganda war.

In a similar vein, the tradition of taking prisoners for ransom and treating them as honoured guests – that most chivalrous of virtues – was abandoned. Instead, prisoners were executed. Richard’s fate echoed that of his namesake son. His blood-soaked corpse was slung on a horse and carried to Pontefract for burial. His body was abused en route before being decapitated.

The brutality of the Lancastrians served to draw allies to Richard’s son, Edward, who was now the legal heir to the throne. The defeat at Wakefield was reversed at Towton, where Edward swept to victory and was named Edward IV.

Boots the Chemist stands where, in 1460, part of the medieval manor house of Wakefield once stood. First mentioned in 1308 as the Earl’s Hall (also known as the New Hall and the Wood Hall), it was a large and prestigious building, grand enough to accommodate the retinue of Earl Warenne, then lord of the manor. Enlarged and modernised over time, by 1460 it had become the largest and grandest house in Wakefield, supplanting the old and outdated castle at Sandal. In 1539, the great hall became the Moot Hall, serving as the courthouse for the manor of Wakefield. The last remnants of the manor were demolished in the 1950s.

“Battlefield discoveries”

We cannot say with certainty where the Battle of Wakefield was fought. It was once believed that the battlefield was at Manygates, but this is incorrect, and the cross there does not mark the spot where the Duke of York was killed. In 1825, while digging out a field boundary dating from 1450–1500 somewhere near Potobello House, bones were discovered alongside a sword. At the time, the bones were believed to be human remains and the sword was thought to be an infantry or bowman’s sidearm or hanger. These finds were taken as evidence that this was the site of the battle, but that conclusion is far from certain.

The bones no longer exist, so we cannot confirm whether they were human. The sword was assumed to be from the battle solely because it was found on land already believed to be the battlefield, but one does not prove the other. As with all battlefield discoveries, caution must be exercised when associating such artefacts with a specific event, especially when the exact find spot is unknown. Many of the supposed ‘facts’ of the battle are merely assumptions, repeated since the 1860s without proper scrutiny.

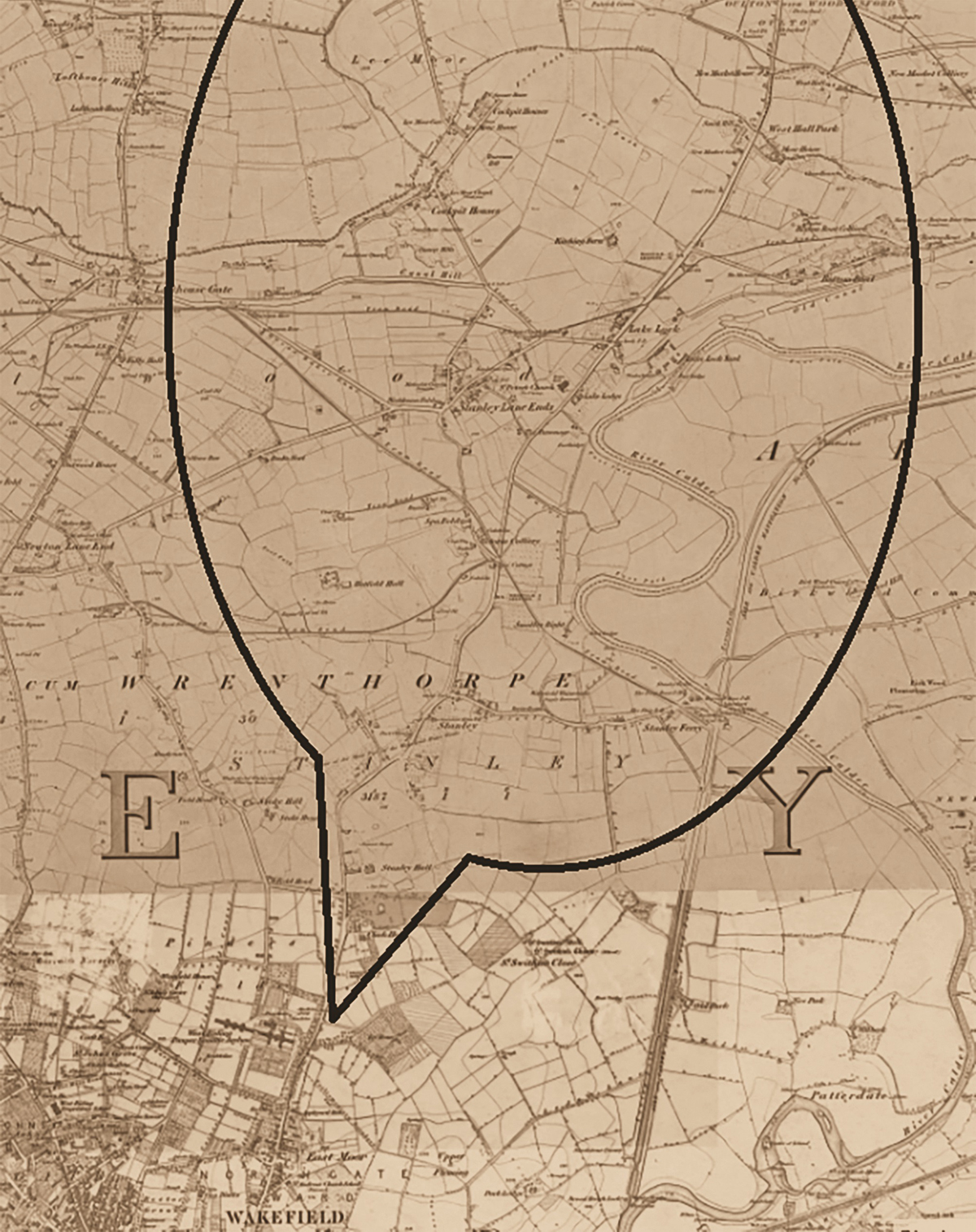

The most likely location of the battlefield is somewhere in Stanley. Accounts from the manor of Wakefield note that cloth bandages were brought from Stanley to treat the wounded. Logic suggests that, if medical supplies were brought from Stanley, then the injured were likely nearby—ergo, the battle occurred in or near Stanley. The earliest account of the battle states the duke was heading north from Wakefield to York. This, combined with eyewitness accounts and the manor of Wakefield records, all point to the fighting taking place north of Wakefield, somewhere around Stanley. It is called the Battle of Wakefield because this is where it ended and where the duke was killed—not where it began.

“Dangers of opposing the Crown”

As can be easily understood, the Battle of Wakefield became a powerful tool of propaganda to support the ailing regime of Henry VIII (r. 1509–47). His unpopular marriage to Anne Boleyn, the break with the papacy and resulting religious upheaval, the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536–37 (a direct reaction to the religious reforms), and the enclosure of common land that sparked rioting in 1535, all contributed to growing resentment against the king, who increasingly appeared tyrannical. The failed military coup known as the Wakefield Plot of March 1541 was followed by a vast—and armed—royal progress to the north that summer.

In the aftermath of these events, it is no surprise that print culture began promoting the Tudor—and therefore Lancastrian—view of history. It served to remind the country of the dangers of opposing the Crown. As such, Richard, Duke of York, had to be portrayed as a usurper to legitimise the Tudor regime and its Lancastrian ties. The more tarnished Richard’s reputation became—just as with his son, Richard III (r. 1452–85)—the more effective the propaganda.

In the aftermath of these events, it is no surprise that print culture began promoting the Tudor—and therefore Lancastrian—view of history. It served to remind the country of the dangers of opposing the Crown. As such, Richard, Duke of York, had to be portrayed as a usurper to legitimise the Tudor regime and its Lancastrian ties. The more tarnished Richard’s reputation became—just as with his son, Richard III (r. 1452–85)—the more effective the propaganda.

Richard’s legacy, like that of his sons, became part of the Tudor misinformation campaign, spearheaded by their chief propagandist, William Shakespeare. Chronicles by Hall, Stowe, Renin, Benet, and Polydore Virgil, among others, along with Shakespeare’s dramatised retellings and the uncritical use of Tudor-era sources, allowed a wholly fictitious narrative of the battle to take root—one that continues to endure. To uncover the truth, we must look beyond the political spin and strive to establish a more accurate historical account.

Article taken from ‘Wakefield’s Military Heritage’ by Paul L. Dawson, published by Amberley Publishing