The Leeds Turnpike Riots of 1753

By Harry Bratley

In the 1740s, merchants and tradesmen in Leeds became frustrated with the poor state of local roads and spearheaded efforts to obtain Acts of Parliament to permit the most important routes to be turnpiked.

Turnpiked roads were routes that were improved and maintained by turnpike trusts. The trusts would make a profit on their capital investments – raised to develop these routes – by charging a toll on users at turnpike gates.

Although the turnpike roads improved communications with the cloth-producing areas to the west of Leeds and the seaports to the east – promoting wool and agricultural trade to the rest of Yorkshire and beyond – the charges were not universally popular. Many turnpike trusts failed to maintain the roads in a decent condition, and consequently traveller resentment grew – a resentment that would turn into hostilities and, eventually, the deaths of several Leeds townspeople.

“Meet the rioters”

In the summer of 1753, an attempt to demolish the gate and houses of the collectors at Harewood Bridge by a mob was defeated and driven back by Edwin Lascelles, the 1st Baron of Harewood, assisted by a number of his tenants and workmen. Notice was sent to Lascelles at Ganthorpe Hall that the rioters intended to demolish the gate at Harewood Bridge and pull down his house. Lascelles armed about 80 of his tenants and servants, who marched to meet the rioters – around 300 strong – armed with swords and clubs.

However, protesters were more successful in demolishing the turnpike gate between Bradford and Leeds, as well as the gates at Halton Dial and Beeston. The dragoons, sent from York to assist in apprehending the rioters in the West Riding, were divided into parties on several turnpikes around Leeds in support of the collectors.

“Inadequate to cope”

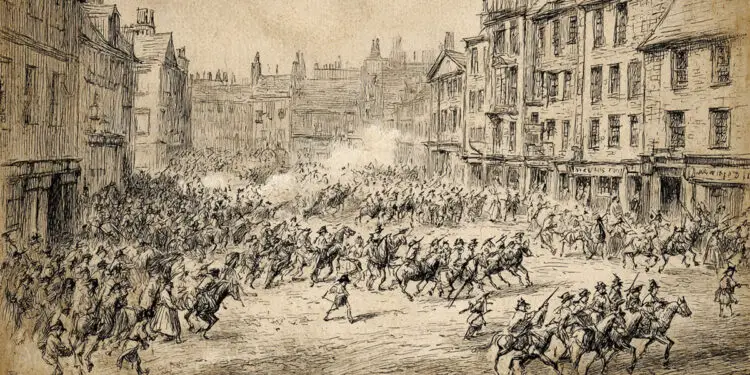

On Saturday 30 June 1753, a carter going through Beeston Turnpike refused to pay the toll. He was seized by the soldiers to be carried before the trustees of the turnpike but was rescued by fellow protesters. Three other rioters were arrested at the Beeston Turnpike and temporarily held in the King’s Arms, which stood on the corner of Duncan Street and Briggate in Leeds (the same site that was later the home of the influential Leeds Mercury newspaper), to be tried by the magistrates.

The mob that had earlier rescued the carter assembled before the inn with the determination of also liberating the three prisoners. After demolishing the inn’s windows and shutters with stones, the magistrates – finding their civil powers inadequate to cope with the rioters – called out the dragoons. The troops were commanded to open fire, first with powder and, when this produced no effect, with ball. The people then fled in all directions, leaving about ten persons killed in the streets and 27 wounded, some of whom later died.

“Notorious”

Sadly, no copies of the Leeds Mercury survive from the time of the riot, but the Derby Mercury reported:

This tragic and notorious riot would, in following years, become known across the country as “The Leeds Fight”.

Despite some opposition to paying tolls, the most dramatic benefits to road users from turnpike trusts were improvements in speed, and the trusts continued to maintain roads well into the 1850s, until competition from the railways and canals became more intense. As a result, the turnpike roads lost their rationale and, in the 1870s, a process of ‘dis-turnpiking’ occurred.

All images are representational