Medieval Women: Voices & Visions – Review

By Clare Jenkins, April 2025

In the light of the recent Supreme Court ruling over the definition of a woman, and the surrounding brouhaha, it’s worth remembering that trans women (and trans men) have always been with us.

Take Eleanor Rykener. Born John Rykener, s/he dressed as a woman, became a sex worker, worked as an embroideress and barmaid, had sex with both men (‘as a woman’, according to her court testimony) and with women (‘as a man’), and was arrested in London for having sex in a public place. When was this? In 1395. Her clients, apparently, included priests – who paid well.

As for current debates about slavery and human trafficking: in the late 15th Century, Maria Moriana, a ‘woman of colour’ possibly from northern Africa, appealed to London’s Court of Chancery in London after her owner imprisoned her because she refused to be sold on to another man. Thirty years earlier, another female slave, 22-year-old Marta, had been trafficked from Russia to be sold in Venice.

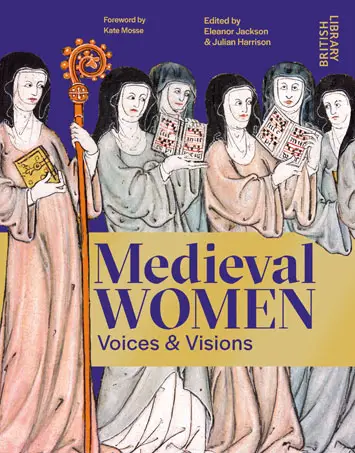

Some of these women featured in the recent British Library exhibition Medieval Women: In Their Own Words. And here they are again in the accompanying book Medieval Women: Voices & Visions, edited by the BL’s Eleanor Jackson and Julian Harrison.

Like the exhibition, the book highlights the lives of medieval women and the wide range of contributions they made to society. Not just as queens like Edward II’s wife Isabella of France or Henry VI’s Margaret of Anjou or, indeed, Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, who fought in the Crusades. But also for their roles in healthcare (some even working as surgeons), in creativity (as artists and composers), in spirituality (as abbesses and anchoresses), in politics, power and protest, including those who supported the Peasants’ Revolt.

In a series of beautifully illustrated essays, medieval experts explore the similarities and differences between women of the Middle Ages and their contemporary counterparts. And the parallels can be startling. One medieval edict, for instance, banned women from being midwives: a distant echo of what’s happened very recently in Afghanistan, where the Taliban have stopped women working in such roles.

As for today’s Iranian authorities dictating women’s code of dress: in 1543, a Bolognese noblewoman called Nicolosa Sanuti protested against an Italian church edict restricting what women could wear. She argued that they had earned the right to wear what they wanted through their ‘virtues, courage, nobility and ingenuity’. Although she was ultimately unsuccessful, her arguments live on. As Calum Cockburn, curator of medieval manuscripts at the British Library, writes, ‘her passionate defence of freedom of dress continues to resonate with issues of gender equality over 500 years later’.

Where other gender issues are concerned, Elma Brenner of the Wellcome Collection argues that medieval medicine acknowledged hermaphroditism, ‘highlighting that the physical differences linked to gender were not always clear-cut. Medieval surgeons certainly recognised that some people had intersex bodies. Furthermore, there were people who did not necessarily identify as the gender corresponding to their sex at birth’.

“Law forbade sex between married couples”

Joan of Arc is described as a ‘queer ancestor’ by Oxford University’s Rowan Wilson, as well as a ‘hero, heretic and feminist icon’. Other women in the book include Christine de Pizan, the first professional woman author in Europe, whose Book of the City of Ladies is an elegant attack on medieval misogyny; the 12th Century composer-nun-visionary abbess Hildegard of Bingen; and the mystic Margery Kempe, who penned the earliest known autobiography in English. Kempe also managed to persuade her husband to agree to a sexless marriage, but only after she’d borne him 14 children. Childbirth itself is widely covered, including advice on how to choose a wet-nurse. (It’s all in the breast milk…)

Joan of Arc is described as a ‘queer ancestor’ by Oxford University’s Rowan Wilson, as well as a ‘hero, heretic and feminist icon’. Other women in the book include Christine de Pizan, the first professional woman author in Europe, whose Book of the City of Ladies is an elegant attack on medieval misogyny; the 12th Century composer-nun-visionary abbess Hildegard of Bingen; and the mystic Margery Kempe, who penned the earliest known autobiography in English. Kempe also managed to persuade her husband to agree to a sexless marriage, but only after she’d borne him 14 children. Childbirth itself is widely covered, including advice on how to choose a wet-nurse. (It’s all in the breast milk…)

Then there’s Lidwina of Schiedam, a Dutch Christian mystic and the patron saint of both ‘chronic pain and ice skating’. Why? Because an ice-skating accident led to a life of pain and paralysis as well as to a deep religious faith.

Not all the women featured are European. York University’s Shazia Jagot, for instance, writes about Shajar al-Durr, the 13th Century female sultan of Egypt and Syria. Jagot’s essay also shows that there were many more creative women in the Islamic world – poets, flautists, musicians, editors – than simply the fictional Scheherazade.

Other chapters explore women as illustrators and booksellers, troubadours, printers, silk workers, stonemasons, ‘ale-wives’, witches, farmers and farm labourers (a lovely illustration from the Luttrell Psalter shows a woman feeding her hens) – and as healers.

One medical compendium included virginity tests and information about contraception – though, given the rules of 12th and 13th Century English Canon law, there probably wouldn’t have been much need for the latter. The law forbade sex between married couples on so many days (Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays as well holy days, Advent and Lent, plus during menstruation, pregnancy and breast-feeding) that you were only left with 93 officially ‘permissible’ days a year to (metaphorically speaking) play with. How did anyone become pregnant?

But then, how much notice of such laws did people actually take? Especially if they read the erotic work of Welsh poet Gwerful Mechain, which included A Poem to the Vagina, with lines like: ‘But what really gets wives going, bless their little cotton socks/Is, pardon me for saying it, the love of good, big …’ (I leave the last word to your imagination).

Sadly, we don’t know what happened to Eleanor Rykener after her arrest. Was she prosecuted and imprisoned, or set free, as Rowan Wilson writes, ‘a remarkable example of a marginalised woman making her way in a difficult world’?

‘Medieval Women: Voices & Visions’, edited by Eleanor Jackson and Julian Harrison, is published

by the British Library